Consumer advocates and doctors are praising reforms that force health insurers to direct more dollars to actual medical care and less to profits and executive bonuses.

"People want to know that their insurance premium dollars are buying them health care coverage, and they don't want it spent on fat salaries for executives or outrageous marketing expenses," said Paula Wade, assistant director of managed markets analysis for HealthLeaders Interstudy in Nashville, a health business research group.

But some in the industry are lamenting the federal health care reforms' impact on small insurance companies, insurance brokers and consumer choice.

Starting in January, health insurers must spend at least 80 percent of their premium revenue on medical claims for individual and small group plans. For large groups, 85 percent of premium dollars must go to health care.

Insurers who don't meet those benchmarks will have to pay rebates to consumers.

LOCAL INSURERS

Cigna Healthcare's medical-loss ratio to date this year was 82.3 percent, spokeswoman Judy Hartling said.

She said officials couldn't comment on the potential impact of medical-loss ratio rules until all details were finalized, but she said the company does not expect reform will slow health care cost increases by regulating premiums.

BlueCross BlueShield of Tennessee's most recently calculated medical-loss ratio from December - for both group and individual under-65 plans - is 85.3 percent, spokeswoman Mary Thompson said.

She also declined to comment on the impact of the new rules before all definitions are finalized.

Wade said that as Americans face a mandate to buy health insurance starting in 2014, oversight of insurers will guarantee that consumers' money will be spent on medical care.

"You need to guarantee there's value there," she said.

PDF: Medical-loss ratio study

An August report from Health Care for America Now, which supported health care reform, found that executives for the 10 largest for-profit insurance companies earned a combined compensation of $228.1 million in 2009, up from $85.5 million in 2008.

"The current structure of our insurance industry is to make sure the insurance industry makes money," said Tony Garr, executive director of the Tennessee Health Care Campaign.

"It's not to make sure that enrollees are covered. It's not to make sure they get the best care, not to make sure the premiums are the lowest possible."

But insurers say the profits are a tiny fraction of the nation's total health care costs. In 2009, insurers' profits were just 0.52 percent of national health expenditures, according to America's Health Insurance Plans, an industry trade group.

PREMIUM OVERSIGHT

Reform also seeks to rein in unreasonable premium rate increases. Last week, $51 million in new federal grants were released to help states keep a closer eye on proposed insurance premium rate increases.

Family premiums for employer-sponsored health coverage have increased by 131 percent in 10 years, according to the nonprofit, nonpartisan Kaiser Family Foundation, a research foundation focused on health care issues.

Dozens of states already exercise some oversight of insurers' rates. Tennessee requires state approval for premium rates in the individual market. Under federal reform, that oversight will expand to include groups.

Georgia officials did not apply for the grants to increase regulation of premiums.

Ken Ellinger, a political science professor at Dalton State College and self-described progressive, said the new rules represent "appropriate government regulation" of the insurance industry.

"It prevents them from just pocketing the money and getting rich, which is pretty much what they're been doing. What company doesn't want to make bigger profits?" he asked.

Even for those with qualms about health reform, the provisions are fair consumer protections, said B.W. Ruffner, a Chattanooga oncologist and president of the Tennessee Medical Association.

"Anything we do that basically throws down the gauntlet that (insurers) can't keep adding more staff and making more attempts to control the health care system at the expense of the premium payers is a good thing," he said.

FINALIZING DETAILS

Regulators are still finalizing how they will define medical-loss ratios, and insurance department officials in Tennessee and Georgia say they're unsure what the impact will be.

Medical-loss ratios vary widely by plan type. Individual plans allocate much more of their premium dollars to administrative costs compared to large group plans, according to a study published in April by the Senate Commerce Committee.

In 2009, the six largest for-profit insurers spent an average of 73.6 percent of individual plan premium dollars on health care, compared to 85.1 percent for large groups. On the low end, Humana spent just 68.1 percent of individual premium revenues on actual medical care in 2009.

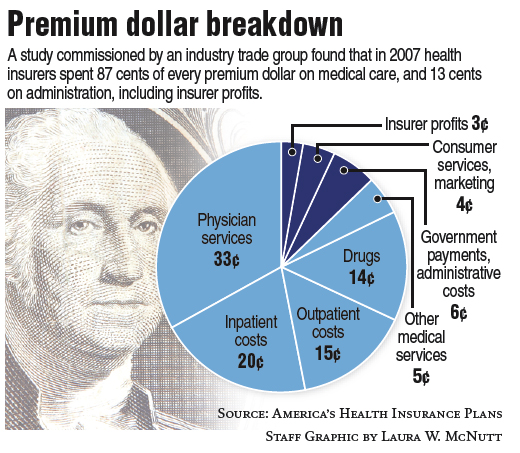

But on average, insurers appear able to meet the new minimum requirements. A study by Pricewaterhouse-Coopers commissioned by America's Health Insurance Plans found that in 2007, about 87 percent of insurance premiums were spent on medical care and 13 percent on administrative costs, including profits.

Wade said that for market dominators such as BlueCross BlueShield of Tennessee, which has 43 percent of the fully insured market in the state, reaching those minimum standards shouldn't be hard.

Nonprofits also benefit from tax benefits and from not having shareholders, which will make the change easier, insurance agents said.

But insurers with a smaller footprint and higher per-customer overhead costs - such as Aetna and United Healthcare in Tennessee - face a greater challenge, Wade said.

Reform could result in smaller insurers merging or abandoning some products to stay profitable, she said, and that could constrain choices for some consumers.

The impact on insurance brokers - those who sell plans to employers and individuals and take part of the premiums as their commission - could be dire, some in the industry said.

Broker commissioners are about 5 percent for small group plans and 1 to 3 percent for larger employers, said local insurance agent Russ Blakely.

Insurance companies looking to rein in expenses could slash those rates, forcing some agents out of business, he said.

"For some brokers, it definitely would affect their ability to remain a broker, particularly smaller agencies with just a handful of people," Blakely said.

Click here to vote in our daily poll: Should insurance companies spend more on health care?

Continue reading by following these links to related stories:

Article: Premium increase modest for Medicare drug plans