ABOUT OPERATION PETER PAN• From December 1960 to October 1962, more than 14,000 Cuban youths were sent by their parents to the United States to prevent their being indoctrinated in Communism.• It is the largest recorded exodus of unaccompanied minors in the Western Hemisphere.• Children were reunited with U.S. relatives or placed in camps in Miami, orphanages, foster homes and boarding schools throughout the country.• Parents later were granted humanitarian visas by the United States and many were reunited with their children.Sources: Operation Pedro Pan Group Inc.; Ed Canler, a Peter Pan kidTIMELINE• January 1959: Fidel Castro's guerrillas defeat Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista's army.• January 1961: The United States breaks diplomatic relations with Cuba.• Jan. 3, 1961: The Catholic Welfare Bureau in Miami is authorized by the U.S. Department of State to notify parents in Cuba that visa requirements have been waived for their children. It was basically the beginning of Operation Peter Pan - Operación Pedro Pan, in Spanish.• April 17-20, 1961: The Bay of Pigs invasion fails to overthrow Castro.• Sept. 20, 1961: Ed Canler is sent to Miami with his older brother.• October 1962: The Cuban Missile Crisis ceases commercial flights between the United States and Cuba for three years.• 2009: The first Peter Pan kids return to Cuba.Source: Encyclopedia Britannica, Operation Pedro Pan Group Inc.

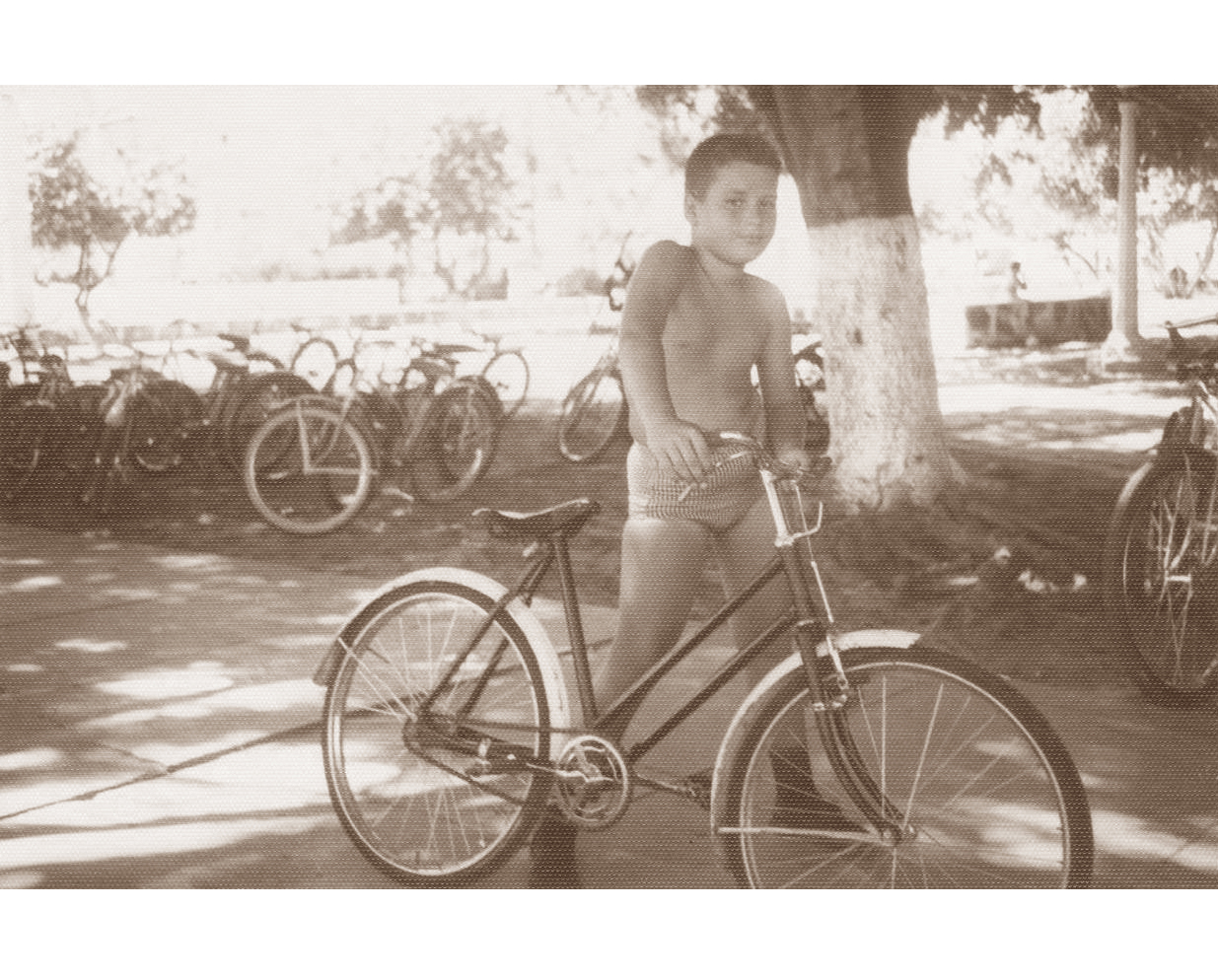

With every step that 10-year-old Ed Canler took, he pushed his foot harder and harder against the ground of Havana's airport, knowing he was not coming back to his native land.

He and a crowd of Cuban children marched like little penguins toward a waiting plane, a piece of cardboard with their names on it attached to their shirts.

"When I let go of my last foot onto the stairway of the plane, I knew that was it," said Canler, now 60. "That's where the break with Cuba occurred."

He didn't fully realize what was happening then, but he had just begun his part in a drama playing out between the United States and Cuba in the years between Fidel Castro's ascent to power in 1959 and the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis that would bring America and Russia to the brink of war.

Canler is one of 14,000 Cuban children brought to the United States from Cuba between 1960 and 1962 under what was dubbed Operation Peter Pan, or Operación Pedro Pan in Spanish. It was the largest recorded exodus of unaccompanied minors in the Western Hemisphere, according to the nonprofit Operation Pedro Pan Group which, among other things, tries to locate Peter Pan kids.

Even so, the operation is a little-known piece of history, one that changed the lives of the children involved, sent many of them to camps or orphanages around the country and meant that some would never see their parents again.

The story of a handful of Peter Pan kids - including Canler - was turned into a documentary, "Operation Peter Pan: Flying Back to Cuba," by American filmmaker Estela Bravo.

"It's a very tragic story of people caught up in the Cold War," Bravo said in a telephone interview from New York, "parents thinking they were going to save their children."

She said she made the documentary because she wanted people to know about a very secretive operation.

"I want people to know what I've seen and feel what I feel," she said of her experience of meeting and working with the Peter Pans.

SENT AWAY

Cuban parents, fearing their children would be indoctrinated into the communist government or sent to work camps, were willing to let go of their kids so they would have the opportunity to grow up in a noncommunist country, said Raquel Iaquinto, Canler's mother, who is now 84.

"The situation was so bad I just wanted to leave," she said from her home in Miami. "But I knew it would be very hard for me to leave."

There are mixed accounts of what exactly happened 50 years ago.

"Pedro Pan was a program created by the Catholic Welfare Bureau of Miami in December 1960 at the request of parents in Cuba to provide an opportunity for them to send their children to Miami," according to the website of the Operation Pedro Pan Group.

Others believe it was a U.S. Central Intelligence Agency operation designed to destabilize the Cuban government.

According to accounts in Bravo's documentary, reports circulated in Cuba that parents would have to forfeit their parental rights under a law to be imposed by Castro's revolutionary government. No such law ever was established or even considered, according to a former Cuban print worker and a U.S. journalist whose father worked for the CIA, both of whom are interviewed in the documentary.

"Given the situation, everything that was going on, the militarization of the whole country, the imprisonment of the opponents, the propaganda that was being shelled out every day, [the supposed new law] became something very believable," said Canler.

"That law was a scam perpetrated by the CIA in an effort to destabilize the Cuban government, basically trying to get the parents to revolt against the Cuban government," he said.

In any case, the children arrived in Miami under the sponsorship of the Catholic Church. The idea was that the parents soon would join their children in the U.S. or that Cuba eventually would be safe enough for the children to return.

Some children were lucky. Canler was reunited in the airport in Los Angeles with his parents and younger brother a year after he left Cuba. But some never saw their parents again.

During Operation Peter Pan, the U.S. government gave visa waivers to Cuban children under 16, but not to the parents.

"For me, I think the biggest question mark I've ever had with the whole operation is that, if the children could come to the United States, why couldn't the parents?" Canler asked.

And why did the Cuban government allow 14,000 children to leave?

Bravo said she was told by sources that Cuban government officials believed that, if they tried to stop them, they would be lending legitimacy to the supposed law.

"And it was the beginning of the revolution," she said. "They weren't organized, they were afraid of stopping the children from leaving. It's a complicated answer, I guess."

Operation Peter Pan has meant different things to all of the now grown men and women. Canler said he doesn't consider himself to be a victim.

"I think it was an operation that was designed for political purposes, Cold War purposes, but which in the end served the majority of the people that participated in it well," he said.

But it's also important to acknowledge there were "damaged goods," he added.

"The church did as well as they could, but all of the sudden they have 14,000 kids with so little infrastructure, some eggs are going to get dropped and some eggs did get dropped. And it's important for us to recognize that, for purposes of historical accuracy, that it did happen," he said.

Angel Carballo, left, a former Pedro Pan child looks at old pictures at Camp Matecumbe, where he spend time after arriving from Cuba in the early sixties, Friday, Nov. 12, 2010 in Miami. The Pedro Pan effort _ the term is Spanish for the fictional character Peter Pan _ was organized at the behest of Cuban parents, fearful of the new communist government's efforts to take control of their children. Most of the refugees spent time in one of several Florida refugee camps before they moved into foster homes or orphanages around the country. (AP Photo/El Nuevo Herald, Pedro Portal )

Angel Carballo, left, a former Pedro Pan child looks at old pictures at Camp Matecumbe, where he spend time after arriving from Cuba in the early sixties, Friday, Nov. 12, 2010 in Miami. The Pedro Pan effort _ the term is Spanish for the fictional character Peter Pan _ was organized at the behest of Cuban parents, fearful of the new communist government's efforts to take control of their children. Most of the refugees spent time in one of several Florida refugee camps before they moved into foster homes or orphanages around the country. (AP Photo/El Nuevo Herald, Pedro Portal )REMEMBERING CUBA

Before Cuba's revolution, Canler remembers very happy times, lots of family living close to one another, when an 8-year-old could roam the streets of Havana by himself, where he could play ball with friends and be free.

Then came the revolution in 1959, when Fidel Castro toppled Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista.

The revolution was an exciting time, Canler recalled. Little boys would follow the revolutionaries as they came down from the mountains where they hid from government forces.

Things quickly started to change, he said, and the promises of a democratic, prosperous Cuba, free of corruption, began to vanish.

By 1961, the U.S. cut all ties with Cuba and, in April of that year, saw the disastrous Bay of Pigs invasion, a failed mission to overthrow Castro.

People started to leave, said Canler, and that was the beginning of Operation Peter Pan as middle- to upper-class parents decided it was safer to send their children to America.

"For us, it was always deemed to be a very temporary situation where we would go to school, learn English and soon enough we would be able to return to Cuba because the thinking was always that the United States would never allow a communist government to persist in Cuba," said Canler.

As it turned out, Castro ruled the country until 2008, when he became ill and resigned as president, a post now filled by his younger brother, Raul Castro.

LEAVING CUBA

The day Canler left Cuba was a Wednesday - Sept. 20, 1961. His mother and father woke him and his older brother Albert, then 13, very early in the morning.

"I remember looking outside of the car, looking at the moon," said Canler.

When he got to the airport and was given his ticket, he was placed with all the other children inside a room surrounded by glass. It became known as la pecera, the fishbowl - parents on one side, children on the other.

Parents tried to talk to their children while they waited, but they couldn't hear each other, said Canler's mother.

All Canler remembers is walking toward the airplane, getting onboard and enjoying a piece of chewing gum. During the revolution, gum had become scarce, he said with a chuckle.

Canler and his brother, along with thousands of other children, were taken to camps in Florida in the span of two years. After the camps got full, children were farmed out to foster homes, orphanages and anywhere else in the country that had room for them.

Canler and his brother went to an orphanage in Lansing, Mich., a place he had never heard of before.

For a 10-year-old, being away from his parents was difficult. He was sad. He was angry. He missed his family. He missed Cuba.

But he soon started adapting and adopting his new country. He learned English; he liked his school. He was being taken care of.

In a year he and his older brother were reunited with their mother, father and 5-year-old brother, who had been too young to go to the U.S. The three obtained humanitarian visas and moved to Los Angeles.

Sisters Betty, left, Martha, second from right, and Maria Muzelle, former Pedro Pan children pose at Camp Matecumbe, where many children were housed after arriving from Cuba in the early sixties, Friday, Nov. 12, 2010 in Miami. The Pedro Pan effort _ the term is Spanish for the fictional character Peter Pan _ was organized at the behest of Cuban parents, fearful of the new communist government's efforts to take control of their children. Most of the refugees spent time in one of several Florida refugee camps before they moved into foster homes or orphanages around the country. (AP Photo/El Nuevo Herald, Pedro Portal )

Sisters Betty, left, Martha, second from right, and Maria Muzelle, former Pedro Pan children pose at Camp Matecumbe, where many children were housed after arriving from Cuba in the early sixties, Friday, Nov. 12, 2010 in Miami. The Pedro Pan effort _ the term is Spanish for the fictional character Peter Pan _ was organized at the behest of Cuban parents, fearful of the new communist government's efforts to take control of their children. Most of the refugees spent time in one of several Florida refugee camps before they moved into foster homes or orphanages around the country. (AP Photo/El Nuevo Herald, Pedro Portal )SETTLING IN

Operation Peter Pan turned Eduardo and Alberto Canler into Ed and Albert, into Cuban-Americans, Ed Canler said, adding that his roots are still Cuban.

He is 6 feet 3, fair and has light brown eyes. When he speaks, he sounds more Southern than Cuban.

"If I hadn't participated, if I hadn't been put in that flight, I would be a Cuban, maybe I would have learned Russian instead of English," he said. "It totally remade me."

To this day, Cuba is a country of "no," he said.

"I've traveled the world, I've read everything I've wanted to read, there has been nothing I haven't done because someone told me you can't do that," he said.

He is an economist and vice president of Textile Rubber & Chemical Co. in Dalton, Ga.

His mother said she doesn't regret sending two of her sons to America.

"It was a very sad day," she said. "I think that was the sacrifice of my life, but I have never second-guessed my decision."

The end of Bravo's documentary shows the first group of Peter Pan kids returning to Cuba in 2009 to close the circle.

"We wanted to put closure to the experience by going back as a group," Canler said. "When we returned as a group, we returned as a statement. We were willing to go back to Cuba, to be at peace with Cuba."

And despite that many of the Cuban children did very well and were reunited with their families, this is something that shouldn't happen again, he said.

"If we need to bring people out and protect them, bring them all out, not only the children," he said.

"To bring kids is as perverse as saying bring the parents but they can't bring the children. We can't imagine a government saying 'we'll let you in but your kids have to stay,'" he added. "Yet we did the opposite."