Officers complete course to learn signs of mental illness

Friday, January 1, 1904

More and more, police officers are being encouraged to recognize the signs of mental illness as they encounter people in their jobs.

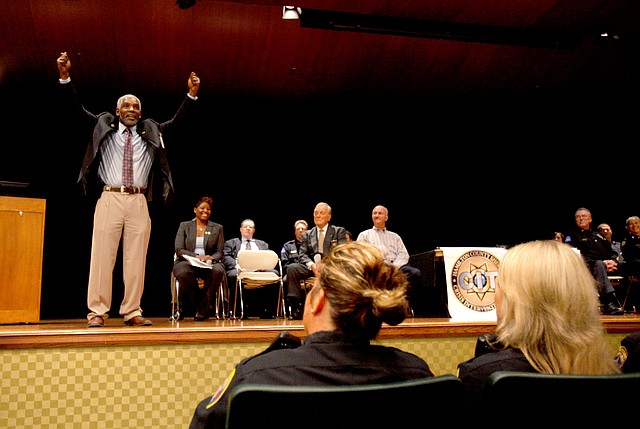

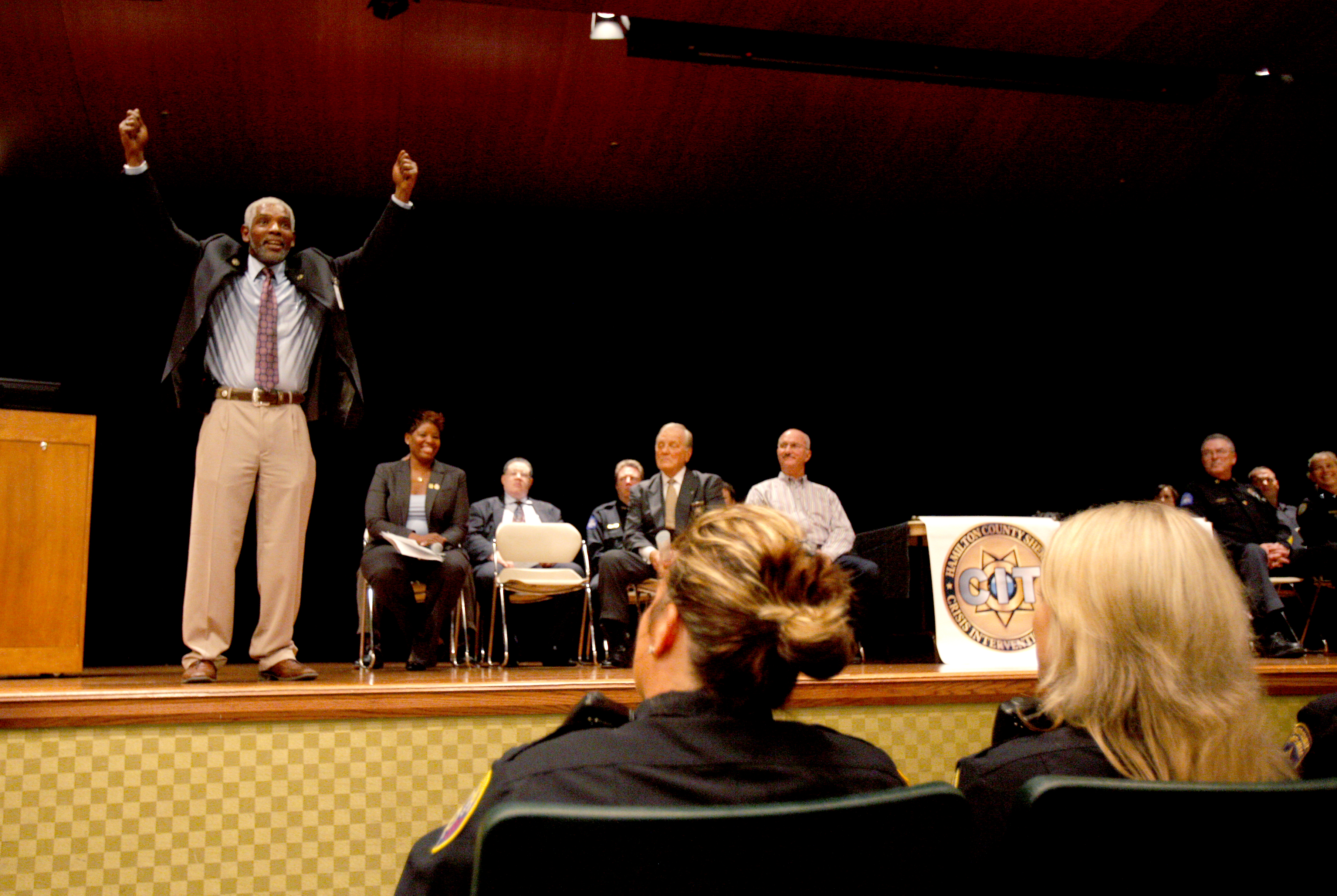

On Friday, 22 people -- mostly sworn law enforcement officers from agencies in Hamilton and Bradley counties -- graduated from a course designed to help them do just that.

The officers and a couple of 911 dispatchers underwent training in the Crisis Intervention Team course, held at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, to learn how to stabilize situations where people may pose a risk to themselves or others.

"It's easy just not to deal with them, or you can be trained to deal with it. I chose to be trained," said A.J. Eady, a corrections officer at the Hamilton County Sheriff's Office who graduated Friday from a program officers can elect to take.

Mental illness is something law enforcement deals with every day.

Just an hour before the graduation, a mentally disturbed woman with a gun threatened a security officer at Patten Towers on East 11th Street.

A Chattanooga Police Department SWAT team was sent to the low-income housing complex, where they discovered that the woman, who had locked herself in her apartment, had been holding a cap gun when she threatened the security officer.

The woman, Patricia Pickett, was talked out of her apartment, then taken to a local hospital for a mental evaluation, said Chattanooga Police Assistant Chief Tim Carroll. No one was injured.

Had the same incident played out more than 20 years ago, Pickett would have gone to jail, he said.

"If someone was acting strange, intoxicated on alcohol or drugs, they went to jail," he said.

The training that officers now receive on dealing with the mentally ill is "a good thing," he said.

"If you get one person to diffuse the situation, it's less heartache on everyone involved," he said.

Rick Mathis, director of research and analysis at the Ochs Center, said he tracks reports filed by officers who graduate from the crisis intervention training. Out of 287 crisis incident reports recorded in 2010 between the Hamilton County Sheriff's Office and Chattanooga Police Department, only one officer and six people were injured during incidents, he said.

During those incidents, weapons were brandished 19 times, or 6 percent of the time, he said.

Out of the 287 incidents, people were taken to a mental health facility 43 percent of the time, 26 percent of the time nothing happened, 29 percent of the time they were taken to a medical facility and 2 percent of the time they were arrested.

"These are people with very unique challenges. You don't want to put somebody in jail who really doesn't need to be there. It's not a good place for them," he said.