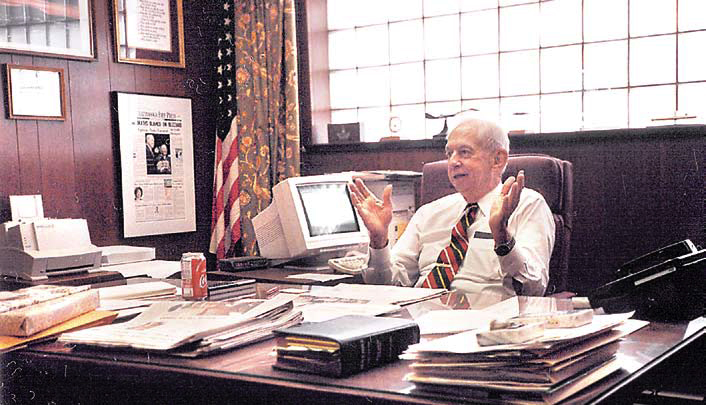

It may take a few years to get the ink out of his veins.On April 18, 70 years to the day after he began his job as a cub reporter at the Chattanooga News-Free Press, Lee Stratton Anderson ends his career at the Chattanooga Times Free Press.

"When you think about the millions of thoughts and words Lee has put to paper over seven decades,"said Jason Taylor, president and general manager of the Times Free Press, "it is nothing short of amazing.It's no doubt those words and his dedication have helped shape Chattanooga for generations to come."

Anderson, 86, who is associate publisher of the newspaper and editor of the Free Press editorial page,was a reporter, editorial page editor and publisher of the Chattanooga Free Press (formerly Chattanooga News-Free Press), the afternoon daily paper that merged with the morning Chattanooga Times to form the Times Free Press in 1999.Walter E. Hussman Jr., chairman of the board of the newspaper, said the longtime newspaperman possesses loyalty, dedication and passion and referred to him as "an inspiration."

"Without all those qualities,"Hussman said, "no one would want to work that long. All those perfectly describe Lee Anderson."Anderson's seven decades are thought to be one of the longest careers in the industry, but a spokeswoman for Editor & Publisher, a journal covering all aspects of the newspaper industry, said the magazine keeps no such records.

The journalism bug bit Anderson,a Kentucky native whose family moved to Chattanooga when he was4, early in life.

As a sixth-grader and having already managed a paper route, he started a newspaper at Glenwood Elementary School - "a purple,dim sort of thing" run off on a ditto machine - and later wrote editorials for the Maroon and White, his newspaper at Chattanooga High School.

At the age of 16, Anderson walked into the Chattanooga News-Free Press Editor W.G. Foster, he said,hired him because "I was warm and 16." Many of the other reporters, Anderson said, had been drafted or volunteered for military service in World War II.

The start of his career was held up several weeks,he said, because he was inthe school's junior play. The play was on a Friday. He started on a Saturday, April 18 ,1942.

Anderson said his study halls late in the school day allowed him to come to the paper about 1 p.m. and work until 5p.m. Saturdays were devoted to writing feature stories.

His first job was "to do rewrites and whatever needed to be done." As additional people left for the service, "I would have the beat of the one who left," he said.Anderson, praised by colleagues at the time as an"eager beaver," showed his drive in incidents such as his 1943 effort to get around wartime restrictions of aerial photography at the new State Guard Armory. In order to get a photo, he persuaded the Chattanooga Fire Department to allow him to climb- unsupported - a seven story fire engine ladder and take the snap.

A photograph of his exploits on the ladder earned him a spot in Life magazine on Dec. 27, 1943.Anderson joined the U.S.Air Force on Feb. 15, 1944,and was due to get his pilot's wings in nine months. However,the war wound down, and he left the service as a cadet in November 1945. Over the years, he told friends his lack of combat experience- although he did rise to the rank of major in the Army Reserve - was one of his biggest disappointments. Returning to the paper,having already covered the police and business beats, he was assigned to cover City Hall, the Hamilton County Courthouse and politics.Eventually, Anderson said,"I had covered every beat atone time or another."

He also was tapped to help editor Brainard Cooper,who was in ill health, write opinion pieces.

Anderson said there were days when he would come to the newspaper at 6 a.m.to write editorials, leave at 9 a.m. to cover the Hamilton County Courthouse, make his 1 p.m. deadline and take classes at the then-University of Chattanooga until 9:30p.m.

"That's when I was the busiest boy you ever saw,"he said. Anderson said he appreciated the step-down in work when he graduated - in three years - in 1948."I feel like I've been semiretired ever since," he said.Anderson, who had assisted Cooper in writing editorials for 10 years, was named editor of the Chattanooga Free Press on April 22, 1958.

"QUINTESSENTIAL BOY SCOUT"

On June 10, 1950, Anderson married Betsy McDonald, the daughter of News-Free Press Publisher Roy McDonald.However, he did not meet her through her father but on a blind date because he happened to have a car. A Sigma Chi buddy, he said, had a date but no car. He had a car - a new 1947Chevrolet convertible from his Air Force savings - but no date. His friend's date was Martha McDonald, whose sister was Betsy, in from college out of town.

Anderson's sense of humor and curiosity about "everything going on in the world" captivated her, Betsy Anderson said. Even more,though, was the fact that he respected his mother so much, she said."I admired that respect,"she said, "and I gleaned that I was going to get some of that, too."

Betsy Anderson said many of her dates with Tat - the nickname family and friends call Anderson - were spent covering political speakers and rallies in surrounding counties. Even when he'd been threatened by a white supremacist and policemen spent the night on Anderson's front lawn, she said, it didn't deter him from picking her up.

The couple honeymooned on a cruise to Cuba, where Anderson would have one of his most hair-raising adventures12 years later. He was a part of group of journalists who had received invitations in 1962 to accompany a Navy convoy to an exercise at Vieques Island, off Puerto Rico. While the convoy was en route to the exercise, President John F.Kennedy informed the nation the Soviet Union was building missile sites in Cuba, 90miles off the U.S. coast, and announced the Navy would block Soviet ships from entering the area.

Anderson's convoy,already in the Caribbean, was in place to form the first ships in the blockade. Before long, though, the journalists- in the midst of the country's biggest story - were quickly whisked down the side of their ship, into a small boat and taken to a destroyer escort, which motored them to Puerto Rico.

Once he was off the escort, he ran for a telephone booth, called the newspaper and made what he believes to be the first news story to come out of the blockade.

The Andersons are parents of two daughters, Corinne Adams and Stewart Anderson, both of Atlanta, and are grandparents of two. In spite of his busy schedule through the years, Anderson always found time for his wife and daughters, his family said.

"The paper's right up there pretty high as for his attention and efforts," said Betsy Anderson, but "family is very, very, very important to him."

The paper was so important,said Corinne Adams,that when he would get calls at home from people who didn't receive their copy, he would return to the newspaper and deliver it himself. "It was a means of upholding his word," she said.

Adams said her father was the "quintessential Boy Scout" and taught her "everything about character."

He modeled integrity,respect and love for one's fellow human beings, "even when you don't like them,"she said. "He never let us use the word 'hate.' He saw God and good in everything."

Adams said Anderson always had a vision for the city in which he was raised and was willing to be a spokesman for it.

"He's so proud of being a Chattanooga boy," she said."The geography is a part of his personal pride and story. It's not a place to live; it's part of his bones, like honoring his father and mother."

Stewart Anderson said her father has been "a terrific example" in how to lead her life, specifically citing his morals, values and how he treats other people.

She said they also have shared a variety of experiences,including staying up to watch election returns, riding an elephant, touring the then-Soviet Union, canoeing Chickamauga Creek and sharing his first two-passenger flight upon his receiving his pilot's license.

He's shown her "not just Anderson said, but also "the exciting cities in the news.He always made time for all of us. Nothing was more important than family."Her "humble" dad, she said, is "everything in my life" and "is always going to be with me."

CONSERVATIVE PIONEER

Before Barry Goldwater and Ronald Reagan became synonymous with conservatism, Lee Anderson was writing principled conservative editorials.

Half a century before today's Republican candidates used the term constitutional conservative, he was using it in his writings. "I've never been political,"Anderson said. "I've never been partisan. I just grew up as a patriotic American." His study of history, his understanding of the principles of the U.S. Constitution and his UC major in history furthered his thinking, and "I grew into being a conservative,"he said.

Anderson said when he was a boy, Tennessee was a one-party state and "everybody was a Democrat." So when he cast his first vote for president in 1948, it was for Strom Thurmond, "a states' rights Democrat."

The newspaper had always had a generally conservative editorial page, he said, so when he began writing editorials in the late1940s they reflected his conservative nature and general philosophy.

Those tenets, Anderson said, came from being "brought up in Sunday school and church," from a "moral background" ingrained in him by the Bible and by his mother, and in "doing the right thing."

When Anderson became the News-Free Press editor at the age of 31, he said, "I was reputed to be the youngest conservative in the neighborhood [of Southern editors]."Over the years, he met presidents from Harry S.Truman to George W. Bush,covered four national political conventions, State of the Union addresses and lunched in the White House with President Reagan several times.

For his writings, Anderson won more than two dozen national Freedoms Foundation awards as well as honors from the likes of the Chattanooga Bar Association, the Tennessee Law Enforcement Officers Association, the Tennessee American Legion, the Chattanooga Sertoma Club and the Daughters of the American Revolution.

However, he said, "being editor and publisher of the Chattanooga Free Press and trying to serve the people of Chattanooga by giving them the news, giving them [opinions from a] principled, conservative, constitutional background and serving the public in public information"have meant the most in his career.

"It was all very impressive because I appreciate the United States of America, I appreciate our Constitution,I appreciate our great country,"Anderson said. "And so it's been a real pleasure to b einvolved in the history of the country and know some of the leaders along the way."

NEWSPAPER WARS

Anderson was just over three weeks into his job when his first experience in Chattanooga's newspaper rivalry occurred, an incident that would portend events for nearly the next 60 years. In 1942, with The Chattanooga Times losing money and the News-Free Press barely in the black, he said, the newspapers drew up a10-year working agreement that was expected to extend the duration of the war.

Newspapers, according to Anderson, "couldn't get lead [for type], couldn't get manpower. A good many were making joint operating agreements."

Eventually, he said, that agreement was extended,with revenue split evenly between the newspapers. But, by the early 1960s, The Times was spending more money and the News-FreePress was bringing in more money, he said.

"It was an inequitable situation," Anderson said, so News-Free Press Publisher "Roy McDonald decided the best thing to do would be to separate the two papers and go to it competitively. "The afternoon newspaper gave notice for dissolution of the operating agreement in 1964, and the newspapers separated in August 1966. The decision, he said, was fraught with peril because the Times had the financial resources of The New York Times behind it and the News-Free Press did not have other backing.

"They said it couldn't be done," Anderson said.The situation got financially worse for the News-Free Press when the Times began to publish an afternoon paper, the Chattanooga Post.

"We were able to get our nose barely above water,"Anderson said, comparing the newspaper to terrapins in a pond he observed as child."That's what the Free Press did. It barely survived. "Then, one day, he said, he recalled a snoozer of a history course at Chattanooga High in which his teacher"droned on" about the Sherman Antitrust Act.

"The deal was," Anderson said, "you could compete as long as you didn't cut your prices below your actual cost." The Times, he said,was "losing money, and they were competing with the Free Press at a loss."In due course , he approached McDonald; then,with McDonald, he talked to the company lawyer and ultimately to the United States Justice Department in Washington,D.C.

When the assistant attorney general referenced a case Anderson had researched at the Chattanooga Public Library, "I knew ... we'd won the case," Anderson said.On Feb. 24, 1970, in a consent decree, the Times was ordered to stop violating the Sherman Antitrust Act, and the News-Free Press was allowed to sue for damages.The News-Free Press sued for $10.5 million, and The Times filed a suit of its own for $21 million.

In late 1971, as the suit was about to go to trial, a settlement was announced,with the Times agreeing to pay the News-Free Press $2.5 million. The newspaper received a cashier's check for the amount on Dec. 10, 1971. Less than two months after the settlement, on Jan.24, 1972, Anderson said, the typographical union that served both papers made a decision to strike only the News-Free Press "because they thought we were more vulnerable economically." Anticipating the walkout, the afternoon newspaper had quickly cross-trained employees and switched to a computerized "cold type" system instead of the lead based "hot type" system on which union members worked.

"There were many violent incidents," Anderson wrote of the strike in a 50th-year history of the newspaper in 1986. "Acid was thrown on cars of those who continued to work. Some employees were threatened and attacked. Many pounds of roofing nails were thrown on newspaper parking lots each night. Thousands of metal balls were lofted by slingshots onto parking areas during the before-daylight hours, breaking countless automobile windshields."The newspaper, which advertised for new employees and received some 2,000 applications, survived and thrived. The union, according to the 50th-year history,spent more than $2 million on the strike. Pickets finally disappeared in 1977.

In 1980, Anderson said, Times management came to News-Free Press management and requested a new joint operating agreement. Unwilling to return to the inequitable split, McDonald offered an agreement in which the News-Free Press received 80 percent of the profits and the Times 20 percent. The Times management agreed to it.

The agreement remained Press and then the Times were purchased in 1998 by WEHCO Media of Little Rock, Ark., Hussman's company." No one can articulate the storied past of this newspaper better than Lee," said Taylor. "His eyes light up as he details the historic battle between the two dailies. It's in those moments, especially, that you realize you're standing next to a giant."

Paul Smith, president of the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, another paper owned by Hussman, said the retiring editor is an "interesting combination."

"He's obviously very passionate about the newspaper business," he sad. "He's very aggressive. I know he was very aggressive during the newspaper competition here with the Times. But he's a real gentleman. A lot of times if you see people who are aggressive, they're not too cordial, sometimes. But he is, and I like that about Lee."

"STILL KICKING"

Anderson, who routinely arrived at the Free Press before 5 a.m. and at the Times Free Press between 6 a.m.and 7 a.m., has nevertheless cultivated an active lifestyle outside the newspaper.

Telling his wife "I had an itch that hadn't been scratched," he fulfilled his Air Force desire and became a pilot, often flying photographers over news sites, buildings and road construction to obtain shots the competitors didn't have. In time, he flew craft ranging from gliders to balloons, once took the controls of an F-16 Air Force jet, and, as a passenger, made aircraft carrier landings and takeoffs in an F-14 jet.

"That was very rewarding to me," Anderson said, his lack of wartime flying having been somewhat mitigated.

He also taught a Bible class at First Presbyterian Church, where he is an elder, for more than four decades."That was a real challenge because there were a lot of people [in it] who knew a lot about the Bible," Anderson said of the class that grew from five couples to more than 400. "So I really had to study to do that."

Hamilton County Court Clerk Bill Knowles said he'd visited the class and vouched for the teacher's soundness."[Lee] is a historian, a Bible scholar and a great promoter of God and country,"he said. "He is a person of sterling character and possesses a friendly personality. He loves Chattanooga and our history. His journalistic skills will be missed by our community."

Over the years, Anderson was fortunate enough to travel to many of the places he taught about in Sunday school and mentioned in news stories, having climbed the Great Wall of China and the Cheops Pyramid. In addition, he has skied in Colorado; tried bullfighting in Mexico; attended a belly dance in Turkey; toured India, Iran and the-then Soviet Union; and explored depths of 800 feet in a Navy submarine. He, his wife, children and grandchildren also made three-generation trips to Egypt and the Greek islands.

In addition, Anderson, an Eagle Scout at 13, has been an author (he's written two books), an architect (he designed two houses in which his family lived on Missionary Ridge), a competitive tennis player, a car lover (he drives around Chattanooga in his signature Corvette) and a businessman (having been involved in a number of successful ventures). One of those, Confederama (now the Battles for Chattanooga Museum), for which his wife once said she painted 5,000 tiny tin soldiers, remains open today on Lookout Mountain. Smith said the editor's varied life has lengthened his career.

"It's a rarity," he said,"because most people don't have the commitment to do that, but I think Lee balanced his life pretty well. He was real active. Probably if he hadn't been active away from the newspaper, he wouldn't have been able to last for 70 years."

Anderson ends his career at the newspaper with the same sunny disposition with which he greeted visitors and politicians of all stripes.

"I love Chattanooga," he said. "I have been here since I was 4 years old, and to be a part of Chattanooga and a part of its civic life and to be able to report on the news and the activities of Chattanooga for 70 years has been a real blessing for me, a real satisfaction. I've worked pretty hard at it [and] I have enjoyed it.

"It has been rewarding since the day I got the job.There have been happier days and harder days, but I've enjoyed all of them [and] I'm still kicking."

Pat Butler, president and chief executive officer of the Association of Public Television Stations board of trustees, longtime news executive and a former News-Free Press staff writer, said he'll never forget that Anderson gave him his first opportunity in journalism, provided encouragement along the way and supplied him with first-rate professional principles to live by.

"The ethos of being careful to get the story right, being fair and civil, and always thinking of the interests of our readers was created and nourished by [him]," he said, "and that was a great gift to our staff and our community." Taylor said, "the community, in turn, is better because of Anderson's presence.

"Lee's personal and professional commitment to this community serves as an inspiration to us all," he said. "He was championing for a better Chattanooga long before it was the buzz-worthy thing to do."

Contact Clint Cooper at ccooper@timesfreepress.comor 423-757-6497.