Levaquin -- emergency only. Toradol -- very little. Valproate. Studol -- a few.

On any given day, the crowded list on the pharmacy whiteboard at Erlanger Health System features 10 to 15 scribbled names, telling the story of record national drug shortages.

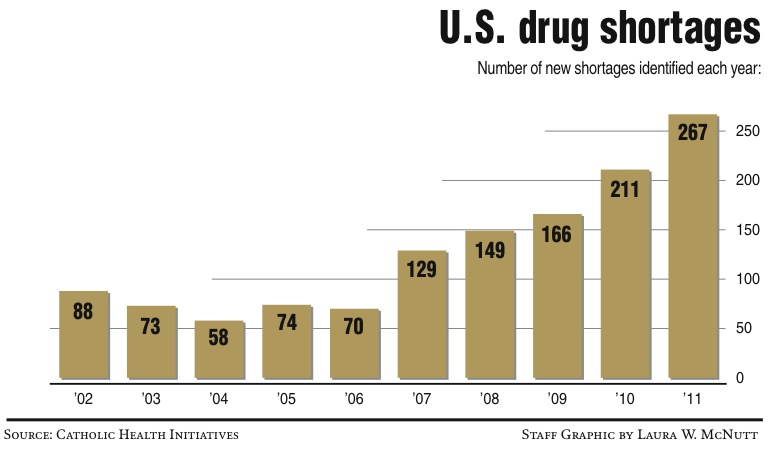

Last year, drug shortages hit record numbers, more than double what they were five years ago, and experts say they expect 2012 to see even higher numbers.

"It's going to get worse before it gets better," warned Dustin Smith, chief operating pharmacist at Erlanger. "Last year we saw a lot of chemotherapy drugs; so far this year it is all over the place."

Drug shortages always have been a part of the health industry, but various facts such as FDA regulations, disruptions in ingredient supplies and consolidation of the generic industry are driving the recent records. Most of those drugs are frequently used generics.

The shortages cost the health industry hundreds of thousands of dollars a year and add countless hours of extra work for pharmacists and drug buyers.

Even more worrying are the patients who don't receive critical cancer treatment drugs, and doctors forced to replace familiar antibiotics and painkillers no longer on their crash carts.

Each change and each substitution leaves room for human error or unknown reactions to new drugs, said Sandy Vredeveld, pharmacy director at Memorial Health Care System.

"Patient safety is a concern for sure," Vredeveld said.

LOCAL IMPACT

Five year ago, local pharmacists and buyers say, drug shortages were a minor part of their lives. Today, they use tracking websites and phone apps every day, often spending hours to track down drugs or find substitutes.

The websites, created by the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists and the FDA, also provide information on substitutions, why the drugs are not available and when the next batch may be produced.

Even if some drugs are available, pharmacists only may be able to get them in pill form or in a different strength, requiring them to repackage, dilute or change the way they administer the medicine.

Large hospitals such as Erlanger and Memorial, which dispense more than 10,000 units of medication a day, are hit hardest by the shortages.

"It gets worse and worse every day," said Rodney Elliott, Memorial's pharmacy purchasing agent. He scrolls through a phone app to check the drugs listed at the moment.

In recent months, shortages have affected a wide range of drugs, often with little warning, Elliot and Smith said.

"It would be easier to tell physicians which lights will be on tomorrow than to tell them which drugs will be available. We have some control over the lights; we have no control over this," Elliot said.

The shortages also create secondary shortages, Vredeveld said. For example, the popular antibiotic Levaquin has been in short supply for months. So many doctors have switched to other antibiotics that shortages are developing there, too.

On Wednesday, a pharmacy tech at Memorial diluted a vial of morphine with saline and repackaged the morphine in syringes. Those morphine syringes -- Memorial uses as many as 1,000 a day -- are not available on the market.

At Erlanger, a drug-dispensing "robot" individually packages patient prescriptions, bar-codes them and bundles a day of prescriptions for nurses to dispense from carts. If a drug is not available, someone will need to find a replacement, check it and ensure it gets on the correct chart -- additional work hours.

Along rows and rows of shelves stocked with drugs, occasional notes warn of limited supplies. One row has vials and vials of Ondansetron, a drug to combat nausea. Erlanger uses about 100 doses a day -- before a new shipment came in, the pharmacy was down to fewer than 50.

"You do what you've got to do to take care of the problem," Smith said.

Hospitals are not the only ones affected. About a month ago, Calhoun, Ga., mom Andrea Everett stopped at her local pharmacy to pick up a supply of insulin pens.

Her 18-year-old son, Heath, has Type 1 diabetes and has to have five or six insulin injections a day. The pharmacist warned Everett that the pens no longer will be available and that Heath will need to use syringes, Everett said.

"It's scary -- he's never used syringes," Everett said. "What if they run out of test strips next?"

REASON FOR SHORTAGES

Pharmacists blame a number of factors for the shortages.

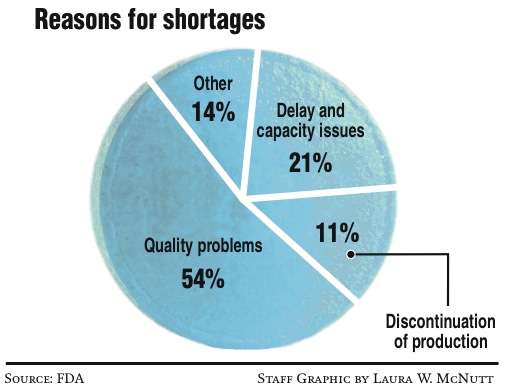

A recent FDA study cited product quality problems for 54 percent of the shortages. Delay and capacity issues created 21 percent of the problem, and discontinuation of production was another 11 percent.

Deb Hood, director of the National Oncology Service Line, recently hosted an informational telephone conference on the drug shortages for Catholic Health Initiatives.

Many of the drugs are generics and/or sterile injectable drugs, which are difficult to manufacture and subject to contamination or quality control problems, Hood said.

The FDA closely regulates production, which makes it difficult to switch from making one drug to another or to add additional production lines, experts said.

Cost also plays a huge role, Hood said.

Generic drugs are not as profitable, and many are made by a limited number of manufacturers. If just one of those has a manufacturing problem, it can create a shortage.

"You get fewer and fewer manufacturers who want to make these drugs," she said. "There is no incentive for these manufacturers to have a high supply."

Raw material shortages of active ingredients coming from China and India also are part of the picture, as well as an increased demand for drugs, both nationally and internationally.

Lastly, all aspects of the health industry -- from drug manufacturers to pharmacies -- operate with much tighter inventories than they used to years ago.

ADDRESSING THE PROBLEM

The FDA has become very active in monitoring drug shortages and working with manufacturers to prevent shortages. Last year, the agency reported it prevented 100 shortages.

In October, President Barack Obama issued an executive order requiring manufacturers to notify the FDA of potential shortages. The FDA was told to add staff to review new manufacturing sites, drugs sites and manufacturing changes.

But the FDA cannot force manufacturers to produce a product or to report plans to stop making one unless they are the only source of that drug, Hood noted.

Elliott said, since that executive order, manufacturers have changed how they operate.

"They are communicating a lot more with us and being more transparent on availability," Elliott said.

But production issues cannot quickly be changed.

There is some discussion of legislative changes, but nothing has been implemented yet, Vredeveld said.

"This administration has been actively involved; they realize the criticality," she said.

Locally, hospitals and pharmacies use national resources but also work with each other. If they are short a drug, they pick up the phone and check if someone else in Chattanooga might have enough to tide them over.

"We are in a reactionary stage at this point," Vredeveld said. "The numbers go up and up every year."