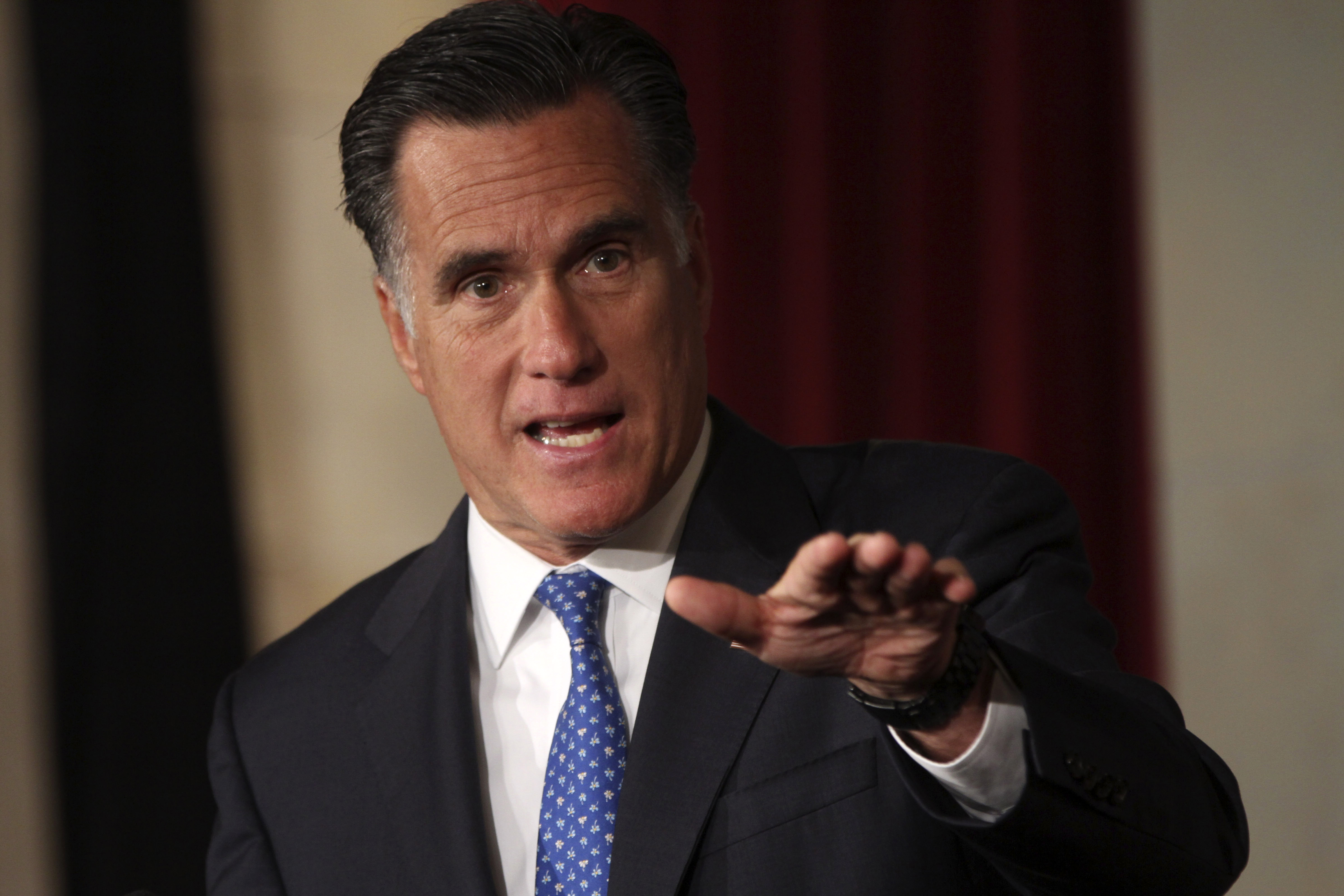

Mitt Romney's radical flip-flop on health care reform and the Obama administration's Affordable Care Act has been politically weird from the start. Before he began condemning the ACA in the GOP presidential primaries, he had accepted wide praise as the governor of Massachusetts for initiating, in 2007, the nation's first state-run universal health care reform act, which pioneered and modeled the use of a mandate requiring most citizens in Massachusetts to purchase health care insurance.

And until last Wednesday, Romney had emphasized that he still believed the ACA's penalty fee for not purchasing insurance was "not a tax." That fits its Republican conception: Republicans first proposed the idea of the purchase mandate in order to advocate for health reform without adopting a single-payer public plan, and a tax to support it. So it was logical that Romney maintained that specific position even after the Supreme Court's Chief Justice John Roberts declared the failure-to-purchase penalty a "tax" in the majority ruling a week earlier upholding the ACA's constitutionality.

But now, flip-flopping again, Romney says he believes the mandate is a "tax," and that that makes the reform plan more objectionable than before. He apparently changed positions to mesh with the new and patently false GOP rant that President Obama "disguised" the tax and deceived Americans about the nature of the health-care reform plan.

Roberts' opinion, to be sure, ruled the penalty fee for not purchasing health insurance was constitutional because it effectively could be seen as a tax properly levied by the federal government to help bring order to, and full participation in, the nation's health care system. None of the court's other eight justices regarded the fee as a tax. But though Roberts' position was unexpected, the four liberals who signed the Roberts' opinion did so because they found the ACA constitutional on other grounds.

Regardless, Roberts' penalty-as-tax ruling can be seen as a logical position for the court. Though long deferred, it follows the legal fabric of Congress' establishment of the Emergency Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA) in 1986, which declared that all Americans had a basic right to health care and could not be legally denied emergency care by hospitals, or dumped on public hospitals. Hence the view of the penalty as a tax may logically be seen as a means, finally, for funding the 26-year-old the emergency care mandate, which has had the effect of shifting the enormous costs for uninsured patients admitted through hospitals' emergency rooms to the bills of insured patients. No one in the health-care industry disputes the onerous burden of such cost-shifting.

Still, Chief Justice Roberts' view of the penalty fee as a tax came as a surprise not just to the Obama administration, which had argued that a penalty fee was needed and legally viable under the Constitution's commerce clause. Virtually every informed judicial observer, whether for or against reform, agreed that the debate was properly framed as to whether a personal mandate to purchase insurance met the test of the commerce clause. Most took that position due to the federal government's gargantuan stake in support of health care generally across the nation, through Medicare, Medicaid, veterans' care and support of public hospitals for disproportional emergency care expenses.

Whatever the constitutional premise that underpins it, universal health care -- and a tax or a penalty fee to make a broader insurance pool possible -- is clearly imperative. If Americans are entitled to emergency care regardless of age, participation in a common, regulated insurance pool surely makes as much sense as state requirements for drivers to purchase automobile liability insurance.

But whether it's a penalty, a tax or simply a legislative requirement as with auto insurance, the label hardly matters. The majority ruling in support of the ACA presents a viable path to secure the sorely needed right of basic comprehensive health care for all Americans at flat, regulated rates, and without capricious barriers like pre-existing conditions and unjust policy limits and cancellations, which are the real death-panel issues with existing insurance system. That is something, at long last, to be celebrated, not condemned.