Mobile Market quenching Chattanooga's food desert (with video)

Friday, January 1, 1904

BY THE NUMBERS

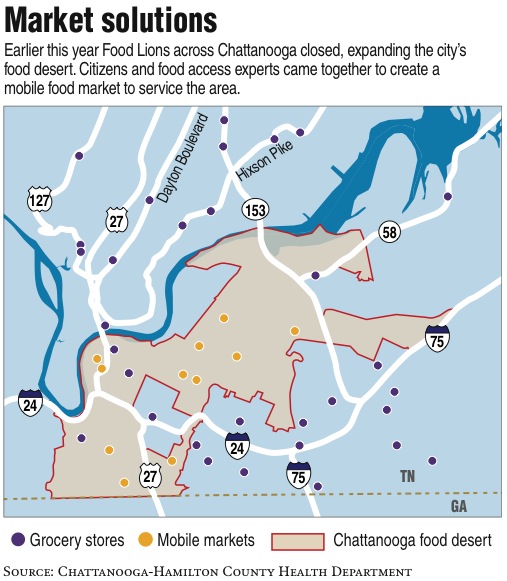

Within Chattanooga's food desert, there are:• 61,924 people• 14,546 children• 18,019 living in poverty• 64 corner stores and gas stations• 23 fast food chain restaurants• 2 grocery storesSource: Chattanooga-Hamilton County Health Department

READ MORE

• Food Lion closings to expand Chattanooga area 'food deserts'• Urban food deserts cut healthy choices• PDF: Ochs Center food report

If it were up to Glenwood resident Christy Montgomery, she and her teenage daughter would eat salads every night.

The two aren't vegetarians, but they love their veggies. They would eat more, but to reach a grocery store with suitable salad stuff, she can only afford to cover a friend's gas money or pay bus fare once a month when her food stamps come in.

"Salad stuff doesn't last long," she said. "I don't have transportation, so I either have to wait on somebody to take me or do without."

Around Chattanooga, about 60,000 residents live in areas where they are forced to rely on the kindness of friends with cars or sometimes take an hours-long bus ride to buy as many groceries as they can carry back home. Such neighborhoods, sometimes called food deserts, are defined as areas in which one-third of the population, or more than 500 people, have low access to healthy food.

Such neighborhoods as Westside, Alton Park, Orchard Knob and East Chattanooga fall within the city's food desert.

When the Food Lion chain closed almost all its Chattanooga stores in January, several local social service groups decided the city needed an immediate solution to the problem rather than wait years -- if ever -- to lure grocers into urban areas.

The groups' new Mobile Market rolled out last week, bringing an 80-item grocery aisle to the backyards of those who need it most. Each week, the minigrocery, housed in a trailer and pulled by a pickup truck, travels to 11 high-need spots across Chattanooga. The market's stock consists of health-oriented foods such as fresh produce and whole-grain breads at prices comparable to a typical grocery store.

Within the coming weeks, the market will accept EBT cards, the new method for using food stamps.

"If something is close, that's going to benefit the whole community," Montgomery said. "I'm glad we're getting one."

John Bilderback, manager of the Chattanooga-Hamilton County Health Department's Step ONE children's program, which helped create the Mobile Market, said the goal is "to make the healthy choice the easy choice to make."

"People may very well want to take home more fruits and vegetables for their children, for themselves, but the reality is it's very difficult for these communities," he said.

Alton Park resident Patricia Fennel, who volunteered to help create the Mobile Market, has dealt with problems similar to Montgomery's for years. She and one of her sons are disabled and have specific diet needs while another son has special developmental needs, and her husband is diabetic. For her family, access to quality food isn't just important, it could be life or death.

But when Fennel goes on her once-monthly shopping trip, she must strike a balance between getting the food her family needs and the food that will last till next month. Sometimes, those choices affect their ability to stay healthy.

"It plays a lot into it because you're not able to get as much of the fresh fruit," she said. "I try to buy stuff I know is not going to ripen real fast or get rotten."

Her story is typical of low-income residents in Chattanooga's expansive food desert. Many people living in the zone have cars, a steady income and no difficulty feeding their families. But for thousands, finding a way to the grocery store, then finding a way to get that food back home, is a constant challenge.

"If you're on food stamps or something, you're buying for the whole month. You don't really have money to run back and forth three times. You've only got about one trip," said James Elder, a Glenwood Apartments resident and chairman of the East Chattanooga Advisory Committee, which oversees part of a $60,000 grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation funding the Mobile Market. "Most fruits and vegetables aren't going to last from the first to the 30th."

Most residents are forced to shop where they can. More often than not, they'll be headed to one of the food desert's 64 corner stores or 23 fast-food chain restaurants, unless they're lucky enough to live within walking distance of the desert's two grocery stores -- Buehler's Food Markets on Market Street and Bi-Lo in St. Elmo.

"We've got to change that ratio of convenience food to healthy food," Bilderback said.

Problems that arise from not getting enough healthy food quickly spill over into other areas, particularly for school-age children, he said.

"When you start to look at that, you connect the dots to other things," Bilderback said. "If you're hungry, you're thinking about food. You're not thinking about math or reading."

The Mobile Market, which is run through the YMCA with the help of the Chattanooga Area Food Bank, is expected to be a first step in addressing that issue. Local and regional philanthropies will fund the initiative for three years, allowing time for the program to establish itself as viable and cost-effective. But the long-term goal is for the market to make the program irrelevant.

"This market can help us make a stronger case for the economic viability of stores in these communities," said Jeff Pfitzer, program director for local food promoters Gaining Ground, which also helped create the market. "It's the holy grail of every neighborhood plan to get a grocery store."

Attracting a grocer is no easy task. It's not unheard of for another grocer to take over abandoned areas such as those left behind by Food Lion, but few new grocery stores are built in urban areas. Pfitzer hopes the Mobile Market will prove there is enough economic incentive for a major company to take the risk and move into the food desert. The more people who shop at the market, low-income or not, the better results from the service.

"It's a start, I guess you could say, of trying to fight the situation that we're in. It's better than doing nothing, because if you do nothing you have nothing," Elder said. "I look at it as a huge step from where we've come."

Community groups have tried to lure such a store into troubled areas for years, but the prospect still seems distant. Still, Elder is hopeful.

"We were looking at this mobile food market as something off into the future, but then, poof! it happened," he said. "A major food chain, it's not impossible that that could happen in the same amount of time."

Contact Carey O'Neil at coneil@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6525. Follow him at twitter.com/careyoneil.