Inside the report that examines what's happening on Chattanooga streets and in our schools

Friday, January 1, 1904

Read moreGerber: Tackling the gang problem

ABOUT THIS STORYEvery statement in the introduction and body of this story is based on findings of Chattanooga's Comprehensive Gang Assessment, a research project compiled by the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga and the Ochs Center for Metropolitan Studies. Researchers surveyed more than 5,000 middle and high school students and more than 800 teachers, principals and school employees.They conducted interviews with gang members, public officials, law enforcement personnel, social workers, clergy and neighborhood activists as well as conducted focus groups with parents, teachers and ex-offenders.Those findings are compiled with crime, demographic and school data to create a 173-page status report on Chattanooga gangs.The assessment included this disclaimer: The gang assessment cannot confirm all of the opinions expressed during the data collection process, but the themes that emerged from community dialogue were repeatedly heard at different forums.WHAT'S NEXTThe Comprehensive Gang Assessment was released Sept. 13.The city's gang task force and City Council have heard presentations by the Ochs Center for Metropolitan Studies and the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, which prepared the report.Anti-gang coordinator Boyd Patterson plans to take the report to the Hamilton County Commission and school board in the coming weeks. Ken Chilton, president of the Ochs Center, has extended an invitation to meet with City Council members individually to discuss the report.In the next three to six months, a steering committee will decide which organizations need to be included on gang intervention teams at the school level and where resources are needed the most.

Mostly, it's what we already knew. The neighborhoods with the gang trouble are mostly black and poor. Too many are without jobs. Too many never finished high school and had babies when they were young.

Children don't have their daddies. Shots can be heard at night.

Sure, gang-related crime is a relatively minor part of overall crime in Chattanooga.

But it's growing. Ask those who live in fear in the neighborhoods and schools where gang influence is strongest.

Partly, it's what we feared.

Guns are easy to come by. Solutions are not.

And partly, it's worse than we could have imagined.

We have condensed the 173-page Chattanooga Gang Assessment down to 101 things you need to know about:

Recruited at 9 years old. Mouth tattoos. And what happens Friday nights at 11.

Gangs are in our neighborhoods. • Gang crimes mostly occur throughout the following neighborhoods: East Chattanooga, Highland Park, Orchard Knob, East Lake, Ridgeside, Ridgedale, Brainerd and Alton Park. • Dodson Avenue seems to be a spine of activity where violent crime, shootings and murders are most concentrated. A climate of fear for some. • The overwhelming majority of residents in areas of high gang activity are law-abiding citizens who suffer because of a small criminal element. • Residents in high-crime communities live in fear -- fear for their children, fear for their property and fear for their lives. One resident lamented, "Criminals complain about their rights being violated by the police, but what about my right to live in a safe neighborhood?" But not for many. • The likelihood of being a victim of gang violence in most communities throughout Hamilton County is low. Yet all of us are affected. • Although all neighborhoods are not equally affected, the gang problem touches everyone in the community. • It affects the quality of schools and the learning environment. • It stresses local law enforcement budgets and the allocation of police personnel. • It contributes to the inefficient use of health care dollars. • It adversely affects Chattanooga's image and the city's appeal and attractiveness to national and global businesses.

There's a dollar cost, too. • The taxpayers' bill starts adding up as soon as a 911 call is placed. One crime can involve dispatchers, police, paramedics, the district attorney, public defenders, parole officers and superior or juvenile court workers. • The Tennessee Department of Corrections estimates it costs $64.83 per day, or $23,663 per year, to incarcerate a prisoner.

Injuries can send costs soaring. • Medical costs for a gunshot injury are likely to average $48,610 per incident. Using that calculation, last year's Christmas Eve shootings racked up $437,490 in health care costs. • If 50 percent of this were paid through Medicaid or uncompensated care payments, then this one incident cost taxpayers $218,475 in medical costs alone.

Chattanooga is not alone. • Large and small cities across the country are struggling with youth violence and gang problems, and none has found a solution.

•••

A breakdown in the family is part of the problem. • Traditional married couples -- husbands and wives -- represent just 35 percent of households in the city. • Seventeen percent of households in Chattanooga are run by women. In the U.S., 13 percent of households are headed by women. • Hispanics have more traditional families than blacks and whites, and more children on average.

Where are all the men? • Blacks, especially men, have a lower life expectancy. • A shortage of black men because of death or incarceration makes it hard for black women to create a traditional family. • More than 80 percent of students surveyed live most of the time with their mothers, while only 40.9 percent also live with their fathers.

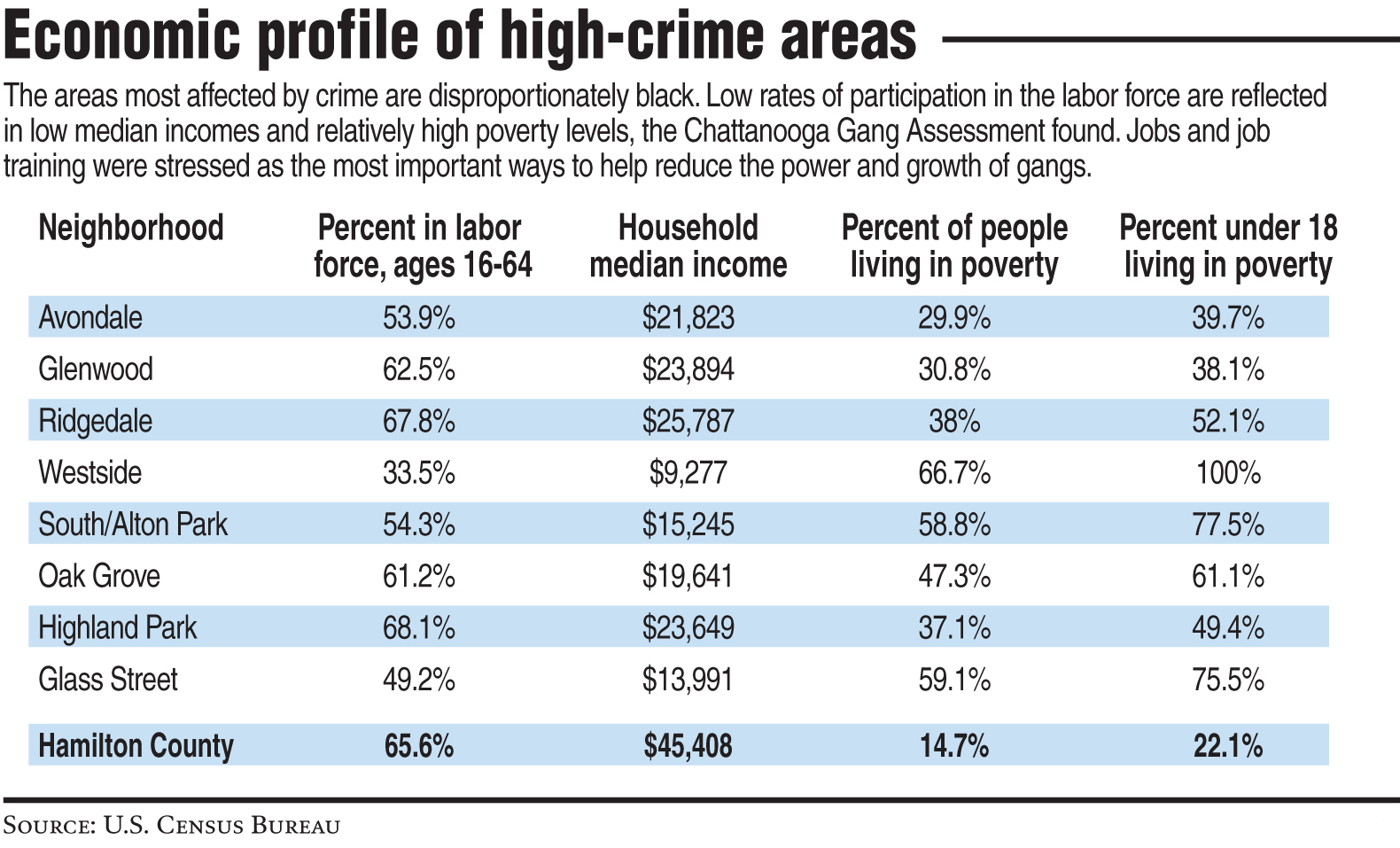

Poverty is a major factor. • Unemployment in the areas of greatest gang activity is highest in Alton Park, 33.8 percent. In Bushtown/Glenwood it's 28.3 percent. • There will be tension between whites and blacks who are competing for manual labor jobs with rising numbers of Hispanics. • Jobs and job training were stressed as the most important ways to help reduce the power and growth of gangs.

Stressed households. • Gang-affiliated respondents indicated a higher frequency of other people (e.g. aunt, uncle, cousins and others) living in their household. • Gang-affiliated students were twice as likely to have five or more siblings in the home than nongang-affiliated students.

Getting to work, and doing without work. • One-quarter of working residents in Westside depend on public transportation to get to work. • The percentage of households receiving cash public assistance is four to 12 times higher in gang-ridden neighborhoods, with the exception of Ridgedale.

•••

Dozens of gangs, hundreds of crimes. • From 2007 to 2011, Chattanooga police recorded 654 gang-related incidents. There were likely far more. • Fifty-nine gangs have been documented by Chattanooga police. Forty of the gangs are considered active.

Some are big, some are small. • The Bloods are entrenched in South Chattanooga, while the Crips are dominant in East Chattanooga. The Gangster Disciples are dispersed throughout the city. Members of those three gangs are involved in 84 percent of gang-related incidents. • These local gangs are not affiliated with the national gangs of the same names. • Chattanooga also has many small, splinter gangs. For example, a notoriously violent group called "Money over Everything," or MOE, is made up primarily of younger teens.

How changing demographics factor in. • Chattanooga's Hispanic population grew 181 percent from 2000 to 2010, to 9,225 people. • Gangs are beginning to emerge in the Hispanic community, where a growing number of children are enrolled in area schools.

Already on the rise. • Officials estimated "two dozen" Hispanic gang members operating in Chattanooga. • Some Hispanic gang members are getting tattoos in their mouths or blacklight tattoos to hide detection of their gang affiliation. • Gang prevention efforts today should focus on Hispanic families and youth.

The crimes gang members commit. • Drugs are the most common gang-related crime, followed by assaults. • Specific gang activities in neighborhoods involve bullying, intimidation, drug sales, loitering, violence and fighting, robberies, break-ins, prostitution, shootings and graffiti. • Local gangs often fight over girls or relationship issues, and these confrontations sometimes include members of the same gang.

Peak times for gang crime. • Fridays are the busiest for gang crime. Tuesdays are the slowest. • Crime peaks at 11 p.m.

Need a gun? No problem. • Gang members reported that it's easy to get guns in Chattanooga. If you have the cash, you can get "whatever you want on the streets," including AK-47s and high-powered rifles. • Many younger members who were interviewed said that 15- to 18-year-olds commonly carry guns for protection. • Only about one-third of suspects brandished a gun in gang-related crimes reported to police.

On the street and on the Internet. • Gang members are tech savvy and use Facebook and other social media to brag about their exploits, glorify their illegal lifestyles and plan activities.

"Big homies" - problem and solution. • Several gang members said young members need guidance, but such leadership is missing because too many "big homies are in jail or dead." • Gang members say older ex-cons who come back to the community are a big problem. • Chattanooga does not have any halfway housing for the largest segment of the returning state prison population. The Salvation Army serves only federal prisoners.

•••

Who they are. • The average gang member in Chattanooga is 23 years old, male and black. • Eighty-nine percent of gang members are black, and 10.5 percent are white. • Whites make up 5.1 percent of suspects in gang-related crimes and 22.9 percent of victims.

An early start. • Recruiting starts at 9. • The majority of gang members joined gangs between the ages of 11 and 16. Some pointed out that they were not made "proper" until ages 16-18.

Is any age off limits? • Some parents actively promote gang culture to their children at even younger ages. Several gang members said it is not uncommon for 3- and 4-year-olds to sling gang signs and speak in gang lingo.

Why they join. • "To get the bullets off your back," one gang member said. • Students said the three most common reasons why other students join gangs are poverty, friends in gangs and a desire for protection. • In gangs, students find protection, but also affection, belonging and love.

Money plays a central role. • "If kids could work, they wouldn't get into gangs for money," one student wrote. • Kids seek recognition and status, and they look up to the older males in the gang who have money, nice clothes, great parties and girls. The only immediate pathway to that lifestyle is through membership in the gang.

•••

Gangs are in our schools. • Many students surveyed feel unsafe at school and at home. One student said, "gangs are really dangerous and the school I go to has a lot of them ... sometimes I don't even want to come to school because I don't feel safe and the gangs are up on me a lot."

And increasing. • Fifty-nine percent of all students, teachers and staff surveyed believe that gang activity in schools is increasing. • Heavier gang activity was reported at high-poverty schools and high schools. • Students associate gangs closely with drugs, especially marijuana, which is taken to schools and sold to other kids.

But they don't stop there. • Fifteen percent of students surveyed reported being gang-affiliated. • The study found gang-affiliated students in all 21 Chattanooga ZIP codes surveyed. • Gang activity takes place most often after school, on personal media, in homes and neighborhoods and restrooms. Hallways, bus stops and recreation centers are also common places. • City recreation centers are not hotbeds of recruitment but an extension of the street.

What students think about gangs. • "I am the leader of a gang that protects people and helps the community," one student wrote. "We are not all violent bloodthirsty kids with guns ... some of us are peaceful kids with guns." • Students had various attitudes on curbing gang influence, ranging from "stop the gangs" to "don't try and stop it you will only make it worse." • Many students think teachers, principals and law enforcement should be tougher on gangs. • Some students were intimidated to not participate in the gang survey.

Proud of it. • Even students who aren't in gangs emulate that lifestyle and cause disruption in school. • Most students talk openly about their gang activity. "I even had one of my seniors do his senior project on his gang affiliation," one teacher said.

Brains aren't valued. • Some of the smartest kids are the ones in the most trouble. • Academic intelligence isn't valued by some of these students' communities, and school doesn't provide any positive ways for them to use their natural leadership abilities. • Many kids prefer standing out as a thug - it's cooler to be suspended for 10 days than to appear dumb in school.

How schools do - and do not - deal with gangs. • While some principals are actively combating gang issues, some teachers said their schools administrators were in denial, ignorant or unwilling to address problems. "[There is] no response, too worried about suspension rates of a few while the whole class is held hostage and cannot learn," one employee wrote.

What teachers had to say. • Many teachers see students "flashing signs," but don't know what any of it means or how to respond. • School employees rarely referenced the role "individual responsibility" plays in students' decisions about gangs. • Many teachers think students should be in school and that suspension is not always the best solution to troubled kids.

•••

Cops and the courts. • Residents complained about the "revolving door" of justice where criminals are arrested but back on the streets within 12 hours.

A problem ignored. • Residents in high-crime neighborhoods are adamant that Chattanooga has had a gang problem for many years that was ignored until high-profile shootings downtown forced leaders to acknowledge the problem. • The prosperity and growth the city markets nationally has not significantly impacted these communities. • Some residents believe that the city's efforts to attract tourism and businesses have taken precedence over community reinvestment.

Trust is lacking. • Many surveyed lack trust in elected officials, church leaders, the criminal justice system, schools, the business community and nonprofits to address the wide range of problems impacting their communities. • Gang members frequently complained about the police "rolling up on us with guns drawn." • Rather than cooperating with police, some residents might choose to let the "streets take care of it."

Who's going to fix this mess? • Some residents place the burden of "doing something" squarely on the shoulders of local government, police, nonprofits and faith-based organizations. • Residents frequently asked "what are they going to do about it" without acknowledging the critical role that parents, guardians and ordinary citizens must play in developing a child's value-system, creating boundaries, participating in educational endeavors, and organizing safe play environments.

Programs matter, but many don't last. • Most of the gang members interviewed participated in youth sports, church groups and other programs offered in their communities as children. • Church programs that work to "save" kids are not substitutes for programs that provide activities, skills and options. • Many programs intended to address the reasons at-risk youth join gangs have been discontinued.

A failure to work together. • There are at least 780 social service programs within a 30-mile radius that are potential sources to address the issues that lead at-risk youth to join gangs. • The services don't work together to combat gangs. • Most programs have not been evaluated to determine if they are achieving their goals.

Face to face. • Community leaders, nonprofits, foundations and civic organizations should participate in interviews with gang members to fully grasp the gang problem. The breadth of information conveyed in interviews is superior to census data, maps and blue-ribbon task forces. Interviews put a human face on the gang problem.

The power of parents. • The quality of parenting and the presence of positive role models make a difference in whether a young person will be likely to get involved in a gang.

Here's how you can help me. • Gang-affiliated kids identified four ways to reduce gang influence: jobs for kids and adults, youth programs, more involved parents and adult mentoring.

The challenge ahead. • The "Chattanooga Way" is renowned for generating results, but the model will be severely tested in transforming the quality of life in neighborhoods mired in multigenerational poverty and a host of social ills.