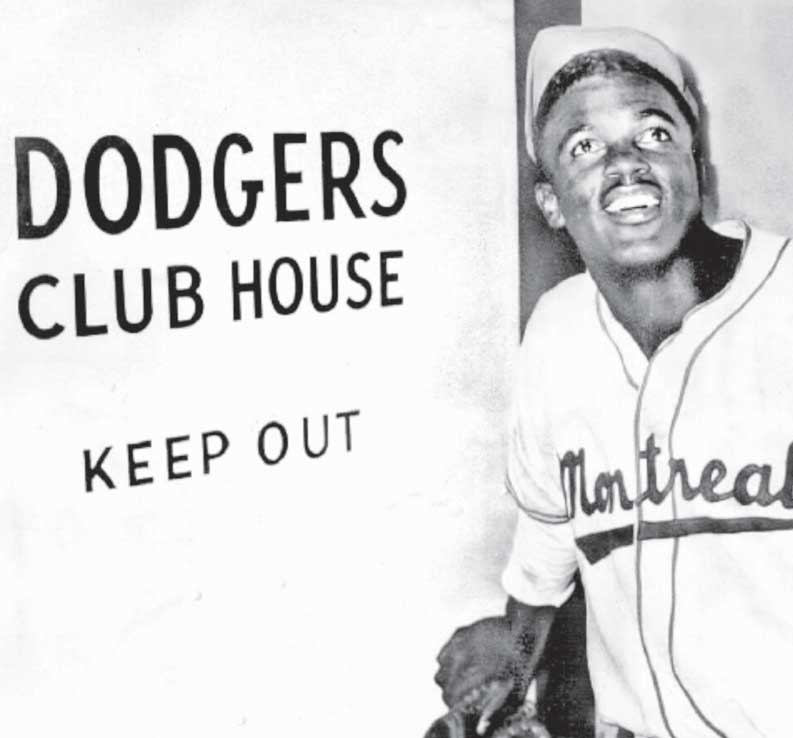

Jackie Robinson, still in his Montreal Royals uniform, reacts after the Brooklyn Dodgers

announce they purchased his contract. Jackie Robinson broke the "color barrier" in professional

sports as the first black player allowed to compete in Major League Baseball when he joined the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947.

Jackie Robinson, still in his Montreal Royals uniform, reacts after the Brooklyn Dodgers

announce they purchased his contract. Jackie Robinson broke the "color barrier" in professional

sports as the first black player allowed to compete in Major League Baseball when he joined the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947.Like a lot of young black men growing up in Chattanooga in the 1940s, James Mapp wanted to play baseball, wanted to become the next Jackie

Robinson long before most people knew who Robinson was.

"Oh, I was a big fan," the 85-year-old head of the city's National Association for the Advancement of Colored People chapter said last week.

"But I couldn't play myself. I had to work from the time I was 12 years old."

Yet while many of us will form our opinions of Robinson through the new movie "42" as it debuts this week throughout the country, Mapp actually met him in 1963, right here in Chattanooga, after he'd retired from baseball and become active in the civil rights movement.

"I was the president of the NAACP here back then, too," Mapp said. "We brought Jackie here hoping to inspire people. I picked him up at the airport and drove him down to the Read House. He was going to speak in a ballroom there. He filled it up and then some. More than 300 people."

Fifty years later, Mapp can't begin to recall exactly what Robinson said that day. But he vividly remembers the then 44-year-old Hall of Famer's demeanor.

"He was very gentlemanly, very stately," Mapp said. "I'll just never forget what kind of gentleman he was. I still keep a photo in my office of Jackie and me at the airport that day."

The movie supposedly tells the story of a somewhat less gentlemanly and stately Robinson, who was boldly asked by Brooklyn Dodgers general manager Branch Rickey (played by Harrison Ford in the film) to break the color barrier in major league baseball.

Even today there are those who will argue that Negro Leagues legend Josh Gibson was a better player than No. 42.

In fact, Larry Doby - who became the first black to play in the American League not long after Robinson joined the National League - once said of Gibson: "One of the things that was disappointing and disheartening to a lot of black players at that time was that Jack was not the best player. The best was Josh Gibson. I think that's one reason why Josh died so early - he was heartbroken."

But with Robinson's UCLA background and well-spoken personality, Rickey apparently saw him as the better choice to execute what may have been the toughest assignment ever undertaken by a black athlete in this country.

How tough was his task? His own teammates and many opposing players threatened to sit out games until National League President Ford Frick and baseball commissioner Happy Chandler told them they'd be suspended. St. Louis Cardinals star Enos "Country" Slaughter opened a seven-inch gash in Robinson's leg while sliding into second base.

Yet somehow, some way, Robinson took it, knowing that any retaliation on his part would only lessen the opportunity for other blacks to follow him.

Perhaps that's why first lady Michelle Obama, upon seeing a private screening of the movie at the White House last week, said, "We walked away just visibly, physically moved by the experience of the movie, of the story. We think that everybody in this country needs to watch this movie."

Though Mapp intends to see it, he doesn't need to watch it to remember what life was like before integration.

"I was a member of the Knothole Gang," he recalled, remembering the late Chattanooga Lookouts owner Joe Engel's kids club that allowed members in free to Lookouts games with a paying adult, "but I always had to watch the games from the colored section. We had to go through the colored entrance."

Nor were they allowed to sit in restaurants or movie theaters with whites.

"We could get food to go," he said, "but from a different entrance."

During his own brave attempts to bring meaningful change to Chattanooga during the 1960s, sugar was put in the gas tank of Mapp's car and his house was bombed.

Yet as wonderful as it would be to report that Mapp sees a different, better future for today's black teenagers and young adults than the difficult one his generation endured, he fears he's seeing a subtle return to racism.

"Until a few years ago I was very positive," he said. "Things were getting better, both in Chattanooga and across the country."

But as he watches gang violence grow and opportunities shrink for blacks throughout the Scenic City in particular and the nation in general, he is concerned that the sacrifices made by Robinson and so many others are having a diminished impact.

"I'm concerned that our young people are becoming very angry," he said. "There's a lack of opportunity; they go to inferior schools. Motivation is being killed."

During a life ended too soon - Robinson died at 53 - he often said of his place in history: "A life is not important except in the impact it has on other lives."

Forty-one years after his death, perhaps the movie "42" can have as profound an impact on today's young lives as Robinson has had on men such as Mapp.