Coast Guard searches ice for servicemen missing since 1942

Wednesday, December 4, 2013

CUMMING, Ga. - Edward Richardson was just a boy when his father, Coast Guard Radioman Benjamin Bottoms, disappeared.

"In some ways, you might say he kind of faded away, since he never came back. He was off like he always was on deployment," he said. "But my mother, it really upset her to no end ... I don't think she ever stopped loving him."

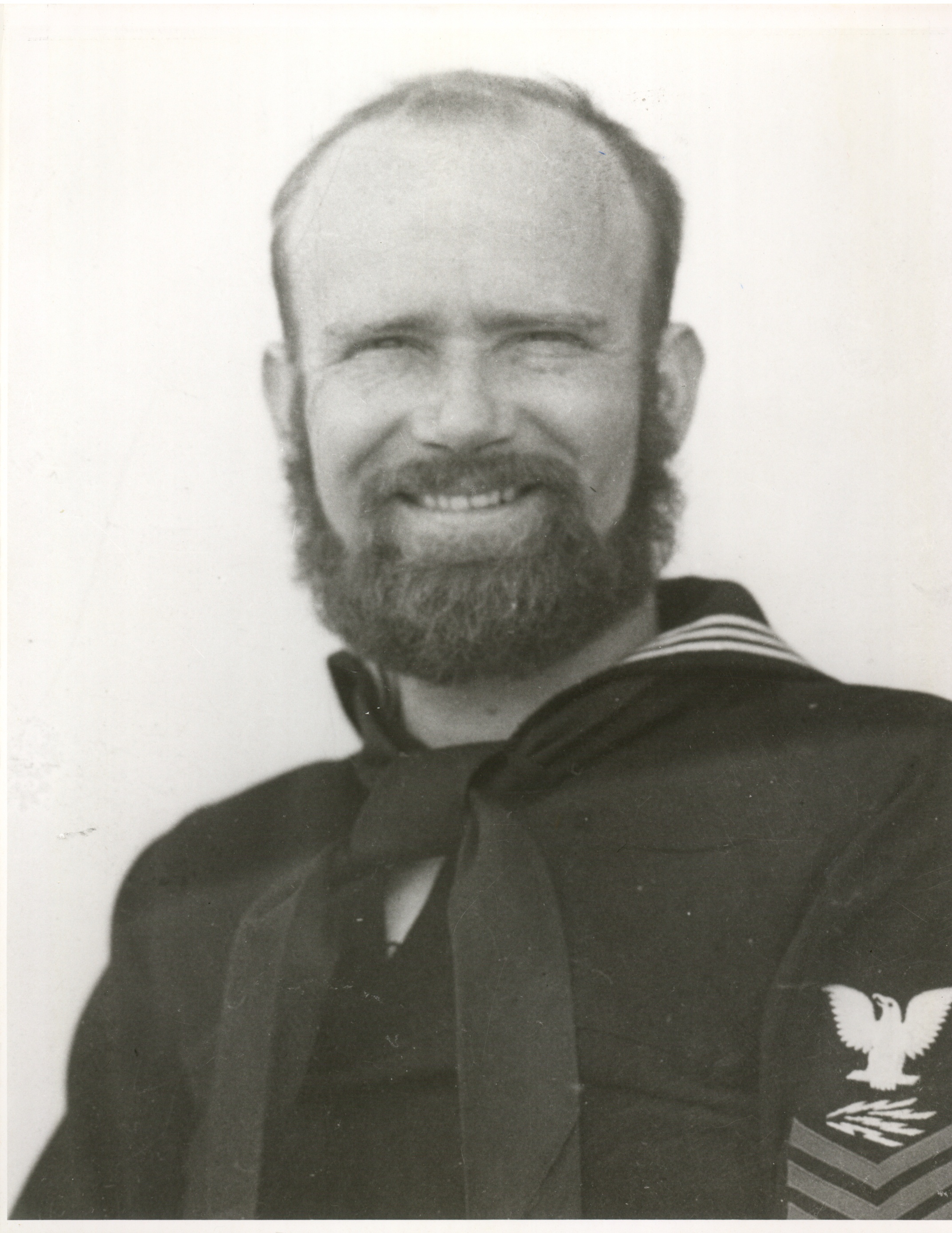

Bottoms would have celebrated his 100th birthday last month. However, just weeks after his 29th birthday, the Cumming native went missing along with pilot Lt. John Pritchard and Army Air Force Cpl. Loren Howarth.

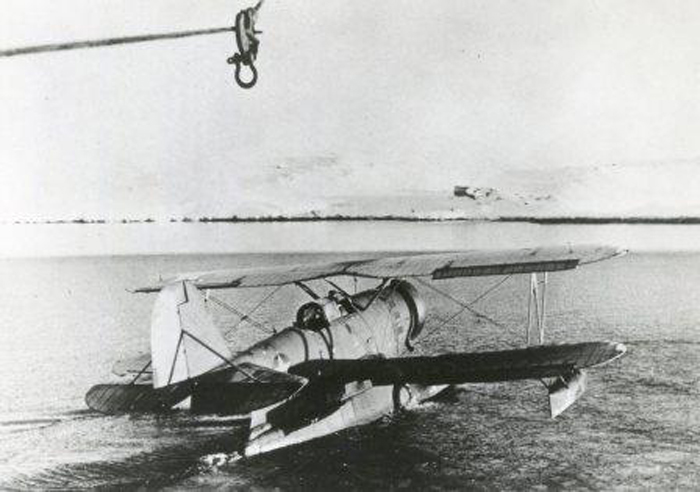

The three were aboard a J2F-4 Grumman Duck. Bottoms and Pritchard had just rescued two Army airmen from a downed B-17 during World War II.

They returned to rescue a third, Howarth, and were en route to the ship when the plane crashed in a snowstorm on a Greenland ice cap in 1942. For more than 70 years, the men's bodies had not been recovered.

"My mother kept thinking - she was still hoping that a couple of years later that maybe the eskimos found him and that he was maybe living up there somewhere," Richardson said.

"I always had thought that maybe he was coming back, because my mother always believed that. I grew up without him. But I have memories of him, I have great memories."

Richardson's mother, Olga, eventually remarried. Her new husband, Ken, would go on to adopt her son. It was a tough decision, Richardson said, one that would make it that much more difficult for the Coast Guard to find him years later, since his last name had changed.

But when he was contacted a few years ago, they told him of efforts to bring Bottoms home, when the so-called "duck hunt" began at Coast Guard headquarters.

It started with paperwork, then a fly-over and surveyors combing the ice. Finally, in 2010, a team of Coast Guard service members, scientists and explorers returned from a mission in Koge Bay, Greenland, where they had found evidence of the crash.

The team melted some of the ice in order to lower a camera. They then were able to see black cables consistent with the specific aircraft. In the nearly three years since, crews have been working on the project.

In a statement, Cmdr. Jim Blow with the U.S. Coast Guard Office of Aviation Forces described the three men aboard the aircraft as "heroes who made the ultimate sacrifice for their country."

"The story of the Grumman Duck reflects the history and the mission of the Coast Guard, and by finding the aircraft we have begun to repay our country's debt to them," he said.

Two more expeditions have followed. However, Blow said the most recent deployment still "did not result in recovering/repatriating remains of the crew."

"Additional evidence of debris of a potential aircraft was identified in the ice, but not recovered due to weather and logistical challenges," he said. "Mission planning is currently under way to capture lessons learned to aid in a future mission."

Richardson isn't the only family member closely following the updates.

Cumming City Councilman Rupert Sexton also has been collecting detailed information about Bottoms, a distant cousin. Sexton's grandmother was a sibling of Bottoms' father.

"Not only is he a relative, but he lost his life trying to protect our nation," Sexton said. Sexton said the family may never have known about the recovery efforts had it not been for his public ancestry information.

"I'm the only contact that ever got established with them ... so the Coast Guard keeps me up to date," he said. "I'm just glad they found my stuff to make the connection. I was the last straw they had."

Of course, finding Sexton, an avid genealogist, led to many other family members, including Dennis Bottoms, whose grandfather was a sibling of Benjamin Bottoms' father.

"We have a family reunion every year at Zion Hill," he said. "My great-grandfather had 12 kids and it's the descendants of those kids. But over 100 years of Bottomses' marrying and moving about, I'm sure there are hundreds that could potentially come, but we get the same 40 or 50 each year.

Like Sexton, Bottoms said he was excited to learn of the Coast Guard efforts.

"I think it would be real nice if they were able to recover his body, that he will have some recognition for his sacrifice ... that would be a nice thing to do," he said.

Benjamin Bottoms grew up in Cumming, but his family moved to Marietta when he was older. He graduated from Marietta High School and, after marrying, moved with Olga to Massachusetts to be near her family.

Though his body never was recovered, he was posthumously given the Distinguished Flying Cross for "heroism and extraordinary achievement in the line of his profession as radioman" when he rescued the two airmen.

The story isn't just told in family circles. Mitchell Zuckoff, a journalism professor at Boston University, has written "Frozen in Time," a book about Bottoms and other Greenland air crashes.

In the book were Alexander Tucciarone and Lloyd Puryear, the two airmen who were saved by Bottoms and Pritchard.

"I'm so grateful for the two men who saved his life," Tucciarone's son, Peter, was quoted as saying. "He lived for another 50 years after that."

Richardson, who now lives in North Carolina, said he's proud of his father. And while his mother is no longer alive, he knows she would be happy if her first husband was returned.

He said his plan would be to bury his father in Marietta National Cemetery, where there's already a headstone and memorial marking, and since that's the town where his father met his mother.

"It's just a little bit of unfinished business," he said of finding his father's remains. "They've already made such an effort to bring him back, I just hope that they're able to. I know my mother would be happy."