A few shotgun shells landed a man 15 years in federal prison

Tuesday, January 27, 2015

ANOTHER STORY Mary Price, vice president of nonprofit advocacy group Families Against Mandatory Minimums, referenced another case that resulted in an unforgiving prison sentence. In 1998, Dan Yirkovsky was remodeling a home in Iowa and found a .22 caliber cartridge beneath some carpet. He put the tiny piece of ammunition aside and continued his work. Sometime later someone reported that Yirkovsky had stolen items and kept them at the home. Police searched the residence, found the bullet and arrested Yirkovsky. Yirkovsky's previous crimes had been petty larceny and aggravated burglary, similar to Ed Young's. His appeals failed and he served a 15-year sentence. A 2010 U.S. Sentencing Commission report showed 5,605 people being held in federal prisons under the Armed Career Criminal Act. Price said there isn't clear data on how many of those incarcerated are held for ammunition possession. She said if people are not swayed by the emotional and human cost to families such as the Youngs, the economic considerations are severe. On average the federal government spends nearly $30,000 a year per prisoner, which would equal $450,000 for Young's full sentence. Source: FAMM, U.S. Sentencing Commission

In some cases, old mistakes echo across the years.

New sins carry the crushing weight of an old life.

In some cases, a criminal past is not forgiven.

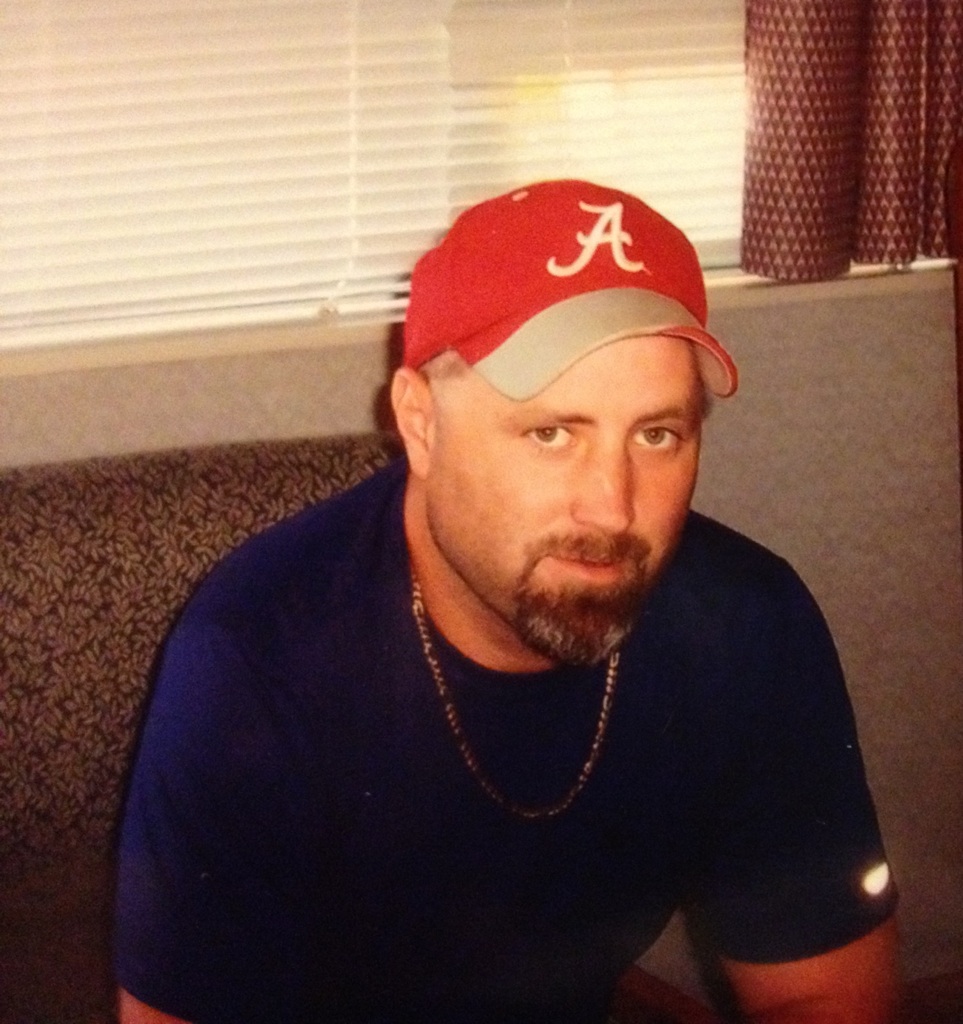

Months before he left state prison on burglary convictions in 1996, Edward Lamar Young told his grandmother he was going to be a different man. He would get work, get married and have a family. The 26-year-old wouldn't steal to get what he needed or wanted.

And soon after he left prison bars behind he fulfilled that promise.

He met and married a woman named Stacy. The couple had four children.

But in late September 2011, he went off track. He stole tools, tires and weightlifting equipment from vehicles and a business warehouse. He even had his son with him on one trip, which added a separate charge.

A video camera recorded the burglaries.

Less than a week later police knocked on the door of his Hixson home. He let them in.

They found the tools, but they found something else too, small items inside a drawer that would escalate his punishment far beyond burglary.

Young admits he's done bad things, but he says he's never carried a weapon, never shed another person's blood. But because of what police found at his house that day -- seven shotgun shells -- his 15-year prison sentence now places him alongside lifelong killers, movie-style gangsters and drug kingpins.

There are homicide convictions that carry sentences half as long in Tennessee state courts.

Laws designed for the worst of the worst, but written broadly enough to ensnare the less dangerous, subject Young to what even his sentencing judge called a Dickensian penalty.

There is a bill in Congress that would give federal judges discretion, untie their hands to ensure punishments fit the crimes.

But that bill is far from passage and would have to apply retroactively, a rarity in many criminal laws, to help Young.

Weeks, maybe months before police came to his home Young had helped a neighbor, a woman named Neva Mumpower. Her husband had died and she wanted to sell some of their older furniture.

She told Young if he hauled it to the flea market she'd split whatever it sold for.

He did, but kept a chest of drawers at his place. A short time later he went through it and found the shells. Young didn't think much of them. He put them away so the kids wouldn't come upon them and went on with his day. He'd get them back to Mumpower later or just throw them away.

Except he didn't.

Young confessed to the burglaries and faced state prison time, probably a few years with the likelihood of parole and probation. Not a proud moment but recoverable.

The 43-year-old man soon discovered that the shotgun shells carried a heavier burden -- a 15-year mandatory federal prison sentence with no possibility of parole.

Standing inside the wood-paneled courtroom in the downtown federal building May 9, Stacy Young knew what was coming but held out a strand of hope. Mercy, maybe.

She listened as the lawyers droned on about legal definitions, criminal histories and what was right, what was fair.

Then the judge told her husband he could speak.

"I just ... I mean, it wasn't ... it wasn't my intent," Ed Young told the judge. "I did find them in the box, and I put them up until I could give them back to her, so my kids wouldn't find them. I don't think I deserve to grow up without my family, and I don't think my family deserves to grow up without me."

The Youngs' oldest son, who is 16, ran out of the courtroom in tears.

The crying family huddled in the hallway after the sentencing.

The youngest son is 6 years old. He'll be 20 when Ed Young leaves federal prison, a 62-year-old man.

Earlier this month Stacy drove her four children to see their father in an Atlanta prison. It was the first time he could hold them in 14 months. All visits to the local jail as he awaited sentencing were over a video monitor.

They almost didn't get in the prison. Only four visitors are allowed at a time. There were five, including her. But a sympathetic guard cut them a break.

Convicted felons are told they no longer can possess firearms. Having a gun, even if the felony was a white-collar crime such as wire fraud, means prison time.

What some may know but Young swears he did not, is that possessing ammunition, say seven shotgun shells, is just as bad.

There's nothing in Young's criminal record to show he's ever been accused of carrying a weapon, even in the 20-year-old burglary convictions. But those burglaries are counted as "violent crimes."

And language is important.

Young's criminal past classified him as an armed career criminal under federal law.

That classification means he faces severe penalties for the rest of his life if he breaks any of the rules.

Young's attorney is flabbergasted.

"I don't think there's anything like it at all," said Chris Varner. "Everything went wrong here."

As far as his legal research shows, it is only under the Armed Career Criminal Act that Young's distant convictions can count against him, Varner said. Other federal sentencing guidelines would not have considered the past convictions because they were so long ago.

Once the charges were filed and the federal grand jury indicted Young, nothing could stop the machine that is federal law.

Prosecutor Chris Poole worked the case. He declined to comment under U.S. Attorney's Office policy not to speak about active cases. Young's case is on appeal to the U.S. 6th Circuit Court of Appeals.

But in court documents, Poole explains to U.S. District Judge Curtis Collier that by definition Young's crimes fit the career criminal law and the minimum sentence is 15 years. The maximum was life.

During the May 9 hearing Collier hinted at his thoughts on the Draconian sentence.

"Mr. Young, I don't know if you read a lot, but there was an author who has written a lot of books, and has some overtones here. His name is Charles Dickens," Collier said.

The judge went on to explain the situation and his own lack of power.

"This is a case where the Congress of the United States has instructed federal district judges like myself to impose a sentence of at least 180 months, that is, 15 years," Collier said. "... This sentence is not so much a punishment for the present crime as it is a punishment for your history of crimes."

The week after the federal sentencing, prosecutors in state court dismissed the burglary and related charges.

Collier mentioned advocacy group Families Against Mandatory Minimums and its work to eliminate such laws at the state and federal level.

FAMM wrote the Justice Safety Valve Act of 2013, which sparked editorials in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal and The Huffington Post.

Mary Price, FAMM vice president, declined to criticize Young's case specifically, but said in armed career criminal cases prosecutors must use discretion to guarantee the punishment is fair.

"A lot of people don't know things like this can happen," Price said. "If the average person knew about this, they would hit their head with the palm of their hand and say, 'You've got to be kidding me.'"

Ohio State law professor Doug Berman, who blogs about sentencing, has written in support of the Justice Safety Valve Act.

Congress wrote the mandatory minimum sentencing laws and the armed career criminal portion to deal with the perceived crack epidemic in the 1980s. But the language is so broad that seemingly innocuous offenses are interpreted as "violent crimes" and trigger stiff punishments.

There have been cases where failing to report to a halfway house on time was classified as a violent crime.

"Unlike what we think happens too much -- defendants get off on a technicality -- the government is kind of throwing the book at this guy over a technicality," Bergman said.

Written arguments and responses to a three-judge panel at the U.S. 6th Circuit Court of Appeals are due in October. Judges often take months or longer to decide.

There are other appeals available if the first level fails, all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. But Price and Bergman say many similar appeals have gone nowhere.

Stacy Young is now a single working mother with a house full of children. She'll haul them down to Atlanta every other week. Two of the children will visit the first day, then they'll stay overnight for the other two to see their father the second day.

Ed Young writes letters nearly every day and says he'll keep writing.

Varner, his attorney, sees the sentence far outweighing the crime and worries what it says about justice.

"This is not who we are, we do not do this as a nation," he said.

Stacy, devastated by the outcome, living with the consequences, sees it much more personally.

"I don't think he should have 15 years for seven shotgun shells," she said. "I think it's crazy."

Contact staff writer Todd South at tsouth@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6347. Follow him on Twitter @tsouthCTFP

News from the future, Jan. 27, 2015: