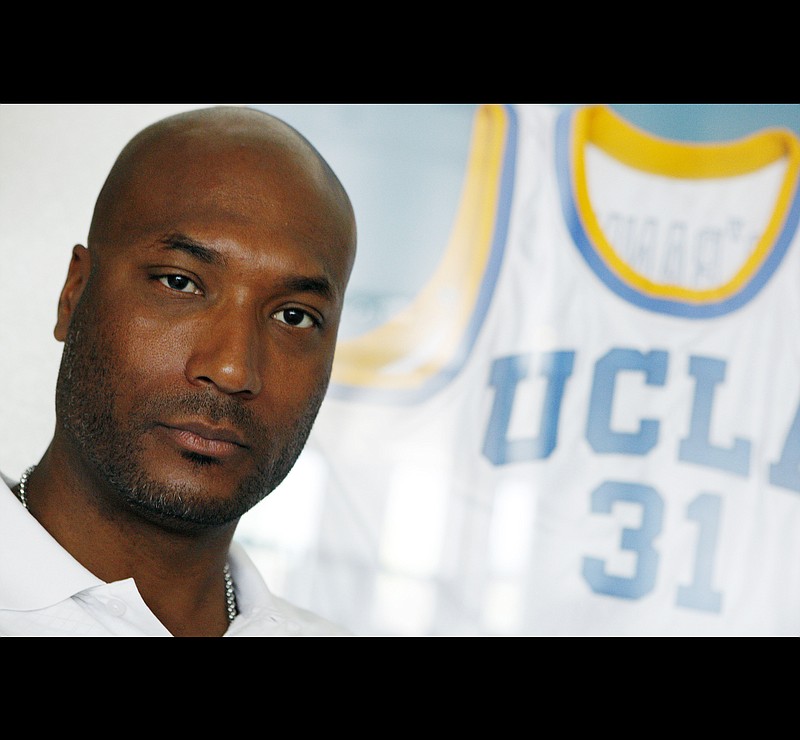

Could Ed O'Bannon do for college athletes what Curt Flood did for professional baseball players more than 40 years ago?

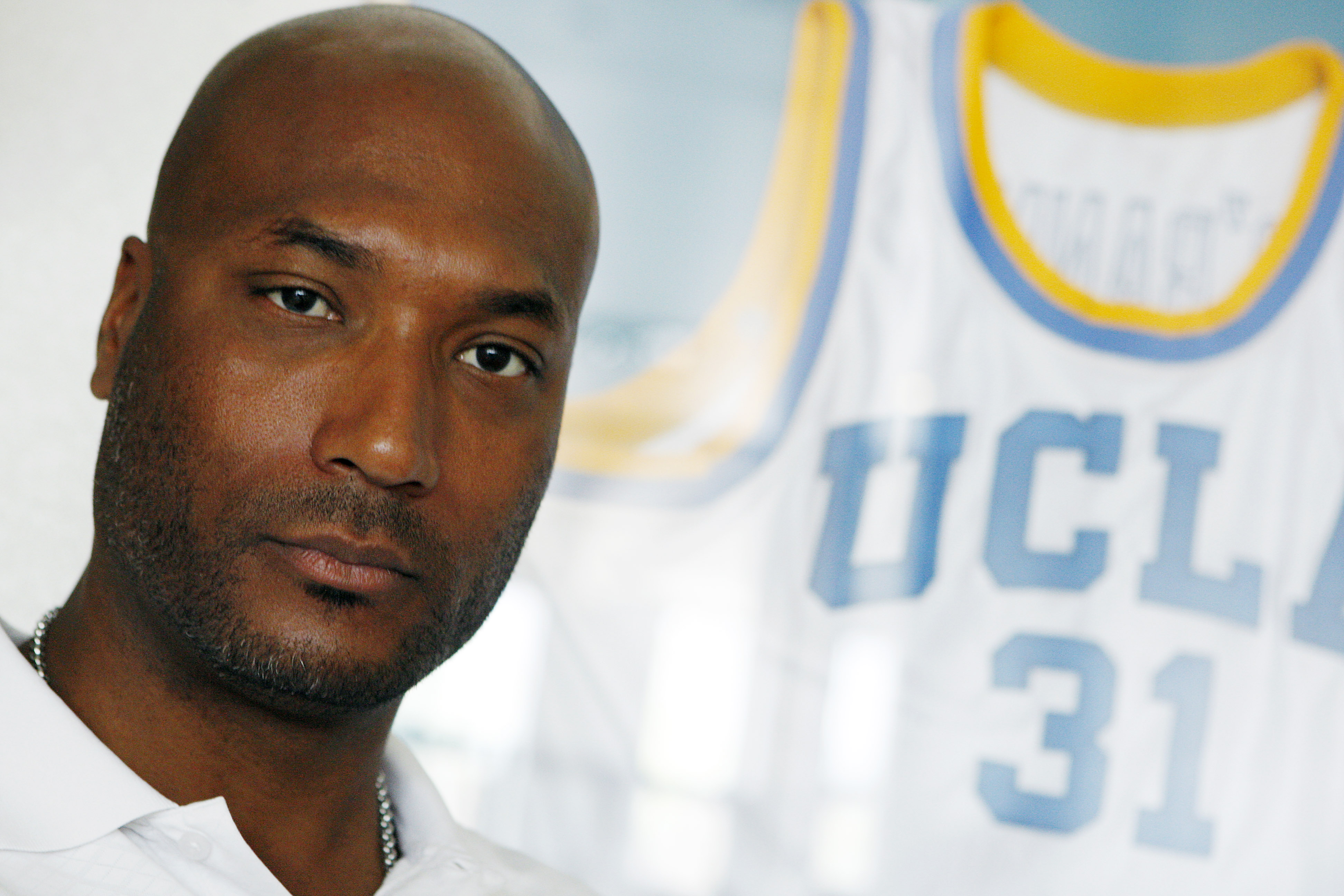

Could the former UCLA basketball star's lawsuit against the NCAA over his right to make money from his likeness in video games and other areas impact college athletics in the same way Flood's refusal to accept a trade from St. Louis to Philadelphia in 1969 eventually led to free agency?

And if so, could O'Bannon also gain as little personally from his potentially historic action as Flood, who wound up bankrupt and out of the sport?

If all of this seems a little foggy for all of you still coming back to earth from the Miami Heat's sizzling defense of their NBA title against the San Antonio Spurs, bear with me.

King James and Co.'s repeat in Thursday night's Game 7 was easily the best sports story of the week, if not the whole year to date. But the most important story for the future of college sports as we know it may have begun earlier in the day Thursday in an Oakland, Calif., courthouse about 3,108 miles from South Beach.

That's where federal judge Claudia Wilken allowed O'Bannon's antitrust lawsuit against the NCAA and co-defendants EA Sports and Collegiate Licensing Company to continue -- at least for now -- and possibly become certified as a class-action suit.

And should that occur -- should she rule for class action -- life as we've known it with the NCAA could cease to exist.

If both former and current college athletes -- specifically big-time football and basketball players -- are allowed to receive a share of media revenue (television dollars) and other commercial products that bear their likenesses, the current college model isn't just remodeled, it's shattered like Humpty Dumpty, perhaps never to be put back together again.

If you're not aware of O'Bannon or the lawsuit, it's understandable. The 40-year-old husband and father of three hasn't been anything approaching a household name since scoring 30 points and pulling down 17 rebounds in UCLA's 1995 NCAA title-game win over Arkansas.

Thanks to bad knees, his NBA career lasted two years before he spent the next seven seasons in Europe. He then became a car salesman in Las Vegas.

But that stunning effort against the Razorbacks inside Seattle's Kingdome on April 3, 1995, earned him the Final Four's Most Outstanding Player award and likely led EA Sports to develop a likeness of him for one of its video games.

When O'Bannon later saw the video game, he decided he'd been wronged and filed a lawsuit. That suit has since been changed to include such former NBA greats as Bill Russell and Oscar Robertson, as well as former Alabama football player Tyrone Prothro, whose playing career was cut short because of a broken leg during his junior season with the Crimson Tide.

Should Wilken rule for class action, it will almost certainly also include current athletes, which would become the NCAA's worst nightmare.

Beyond that, and this point cannot be overlooked, the man driving this lawsuit from behind the curtain has been Sonny Vaccaro, the former sneaker execx who long has despised the NCAA.

Vaccaro told the Birmingham News last week that he got involved in the suit -- which was first filed in its current form in 2009 -- because of a news conference involving the late NCAA president Myles Brand and retiring NBA commissioner David Stern.

The presser was to announce a joint initiative between the NCAA and the NBA designed to "clean up" summer high school hoops, which is where Vaccaro first made his name.

"I can still see David Stern and Myles Brand standing at the Final Four podium saying they're going to get rid of the ills of basketball," Vaccaro told the newspaper. "To me, it was a combination of my worst fears where a professional entity and amateur entity become partners to control a business they had no business being part of."

Anyone who's followed AAU summer ball over the years might dispute that, but this is clearly personal for Vaccaro, who first befriended O'Bannon and his younger brother Charles during their prep days in Los Angeles.

In the same article, O'Bannon said, "Mr. Vaccaro is my mentor personally. Without him, we wouldn't be where we are."

Technically, where this suit is remains up in the air. The fact that Judge Wilken asked the plaintiffs to amend the suit to include current players would seem to be a victory for O'Bannon, since why would you have them go to that trouble if you weren't strongly leaning toward class-action certification?

Then again, that could also help the NCAA, which could then argue the difficulty of handing out equal payments to all athletes, some of whom -- a star quarterback, for example -- would theoretically deserve a much larger cut of the pie than the last guy on the bench.

Wilken even questioned the plaintiffs' attorneys about that exact scenario, perhaps mindful that class-action suits are designed to award all plaintiffs equally.

But let's be clear. This is a very big pie. The NCAA recently inked a new TV deal worth 10.8 billion dollars for its men's basketball tourney. While hamburger giant McDonald's has grown at an annual rate of 7.7 percent the last 30 years, the NCAA has seen an increase of 8.2 percent. Big business, indeed.

No ruling is expected until the end of the summer at the earliest and her options remain threefold: Grant complete certification to both past and current athletes; certify O'Bannon's class of past grievances, but not current players; or deny certification completely.

Wilken's past judgments are said to lean toward complete certification.

There are no simple solutions here. And the humongous elephant in the room is what becomes of nonrevenue sports. With most schools already running in the red, who funds those sports if the television revenue pie for the schools is sliced in half, as the plaintiffs prefer?

Given all that, here's one 56-year-old sports writer's opinion as universities, the NCAA, athletes and the public all begin to decide the true value of an athletic scholarship and college degree.

First, the schools need to hammer home the worth of a diploma and the vast expenses surrounding an athlete's four (or five) years on scholarship.

Second, allow the stars to accrue royalties on jerseys and such while in school to be paid when they earn a degree. This is already in the works on video games. It needs to be available on everything else where the profit could be tied to the success of the athlete.

Third, the athletes need to accept the fact that their first pro contracts are often driven by their college successes. Without college, most would have much less name recognition or proof of their ability to compete admirably against their sport's elite. Call it paying your dues.

Said O'Bannon to the assembled media after Thursday's court date: "Initially, when we filed the lawsuit, I was told it was going to get pretty big. I didn't realize it would get as big as it has. People are looking at what's going on [with the NCAA] and see there's a better way of doing business."

Or at least a different way. Better depends on whether you're for the plaintiffs or defendants.

Contact Mark Wiedmer at mwiedmer@timesfreepress.com