Pulling back the curtain on hospital pricing

Friday, January 1, 1904

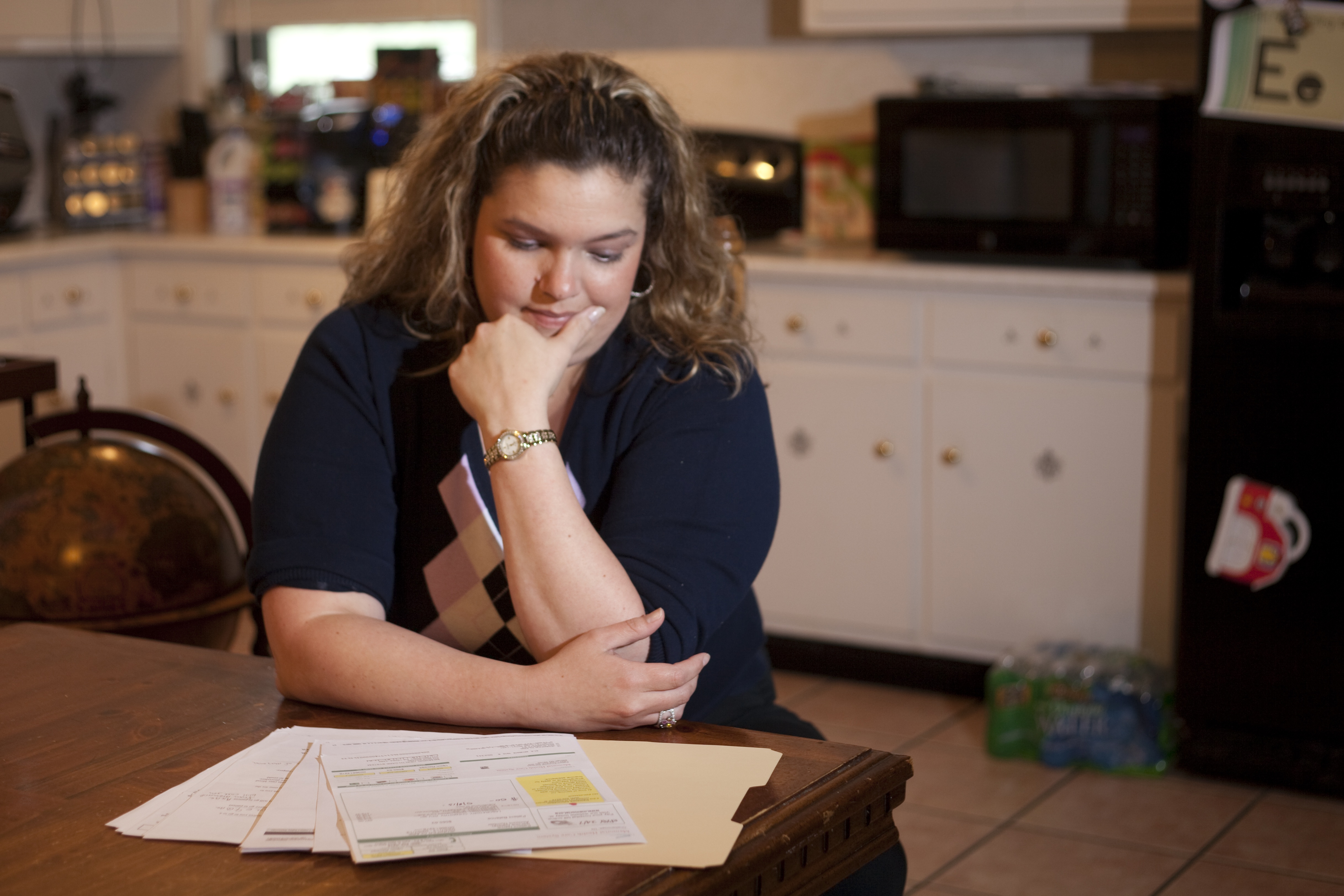

It was a kidney stone smaller than a nickel that showed Jennifer Clark how giant the disparities are in the health care industry.

Clark, who lives in Fort Oglethorpe, first went to an emergency room in March for a pain in her left side that the mother of four said was worse than childbirth.

After two hours and several procedures, she was told she had a kidney stone, and was charged about $7,000.

Clark, 32, is uninsured. Her husband works, but his company's family plan was too expensive for the couple to justify paying.

Because of that, the hospital gave her a discount. She ended up paying a tenth of the first charge.

At a follow-up appointment, which cost an additional $1,600, she learned she needed a procedure called a lithotripsy to dissolve the kidney stone.

She was referred to a Chattanooga-area hospital, where she was told the procedure would cost about $8,600. Because she was a self-payer, the hospital said that was roughly half off their "listed charge."

But it was still too high for Clark.

"I guess I had an epiphany," she says. "I just decided ... I'm going to shop for a procedure."

She started calling facilities outside Chattanooga within a two-hour radius. She found hospitals in the Atlanta area that would do the procedure for less -- but she settled on a facility in Franklin, Tenn., that agreed to charge her less than half what the Chattanooga hospital proposed and a third less than the cost in the Atlanta area.

The whole episode left Clark feeling like she had fallen down a rabbit hole.

"If it is that much of a difference at hospitals just two hours away ... something is not right with our health care," Clark said. "How can it be that much of a difference? What does it actually cost?"

The U.S. government says it is trying to answer some of those questions by releasing a mammoth database showing what 3,300 American hospitals bill Medicare for 100 medical procedures. The bird's-eye view shows startling variations in charges for the same procedure, including those at a dozen medical centers in the tri-state region.

One hospital in Hamilton County charges $32,000 to insert a pacemaker, while another in Bradley County charges more than three times as much for the same thing.

By making the data public, officials with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services say they want to pry the lid off mysterious pricing methods and empower patients to be better health care shoppers

But will this data drop really help consumers?

Like everything in the health care world, it's complicated.

ONE PACEMAKER, MANY PRICES

Start with the permanent pacemaker insertion.

It's generally considered a simple surgery, where the pacemaker is inserted in the chest and wires are threaded to the heart. So what's the price tag?

The Medicare data show prices on what each hospital calls a chargemaster-- the hospital's list of what procedures and devices cost.

Locally, the charge for a pacemaker insertion is billed at an average of $32,240 at Erlanger Health System; $40,416 at Memorial Health Care System; $76,259 at Parkridge Medical Center; and $105,988 at SkyRidge Medical Center in Cleveland, Tenn.

There are some reasons for disparities in pricing, hospital officials say. Some hospitals take on more low-income patients, or run a teaching facility. Cost of living comes into play. And a patient's general condition must be taken into account. In that sense, no two pacemaker insertions are exactly alike.

But critics say the spectrum of charges for single procedures still is too wide to justify.

Jonathan Blum, deputy administrator for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, said last week he did not see "any business reason for why there is so much variation in the data."

He added that higher charges do not reflect better care. Other experts say the numbers illustrate the overall rise in health care spending and inherent disparities in medical-related pricing.

Gordon Bonnyman, director of the nonprofit Tennessee Justice Center, an advocate for health care for the poor, has his own view of the data.

"Bottom line, I think it's important for educating the public about how variable and crazy this pricing is," said Bonnyman. "But the information is less useful for a consumer to shop around with."

Here's why: Virtually no one will pay the listed charges.

That's because Medicare pays fixed prices for procedures and devices, with little room for variation. And insurance companies privately negotiate rates for each procedure that are significantly lower than what's on the chargemaster. Ironically, someone could end up paying less for a pacemaker at one of the "higher-charging" hospitals than a "lower-charging" one based on the contract rate his or her insurance company hammered out with the hospital.

"Until insurance companies put what they pay online, consumers aren't going to be able to compare-shop," said Tennessee Hospital Association President Craig Becker, whose organization has publicized a Tennessee-specific list of hospital charges for several years.

"Charges don't really mean anything," he said.

CHARGE VS. COST

So why even have the chargemaster?

"The charge exists largely for historical reasons," said Steve Johnson, Erlanger's vice president of government and payer relations. "In the old days, charges did factor significantly into reimbursement."

Now, insurance companies configure rates based on diagnosis-related groups. But Medicare law still requires hospitals to submit bills based on a "uniform chargemaster."

Experts say chargemaster data are most valuable to patients who are uninsured, or self-insured with high deductibles. They are the ones whose costs are still tied most closely to the chargemaster, though Tennessee law protects the uninsured from charges over a certain threshold.

Some critics say hospitals still benefit from inflating charges, as some health insurers still calculate reimbursements through those numbers. Others say that certain high charges reflect unfair mark-ups on devices and drugs.

All this shifts back to Carr's second question about her kidney stone removal: How much does it cost? Is there a universal, baseline cost for a lithotripsy?

With health care, "cost" is a squishy word.

"If it's a patient asking, they want to know what's coming out of their pocket," said Johnson. "For an insurance company, cost is hospital reimbursement. At the hospital, I'm thinking of salaries, supplies, equipment. 'Cost' is different for each hospital, patient and insurance company. And all that is different from charges."

Hospitals do conduct surveys to gauge and define price ranges in other ways. Every hospital has a "pricing philosophy," said Johnson.

"We try to stay in the middle of the road," he said.

Parkridge Health System released a statement saying that a patient's type of coverage carries much more weight than what the chargemaster says. The statement said Parkridge "supports transparency efforts" by providing pricing information on its website.

Memorial's chief financial officer, Cheryl Sadro, said charges didn't carry much weight. And yet she also said the charges showed Memorial's price structure to be "competitive."

"It shows that we are a low-cost, high-quality provider," she said.

All of the puzzling factors -- the algorithms for value, the jargon, the seemingly shape-shifting nature of costs and charges -- is why publishing this chargemaster data, limitations and all, is still important, said Bonnyman. It lays the groundwork for consumer understanding.

"No other industry works like this, where the consumer doesn't know what the prices are; where they are incapable of understanding or controlling the aspects of the procedure they're paying for and what the doctor is deciding for them; and where there is little to no accountability for the quality of the product," Bonnyman said. "There's nothing out there in the real world that everyday people encounter that is remotely like this."

Local hospital officials argue that yes, there is no other business like health care, but say that's because health care involves unique patients with unique medical needs and unique incomes.

Complexities aside, one thing is true, said Becker: Some hospitals are more expensive than others, with big differences even at a local level.

"I would strongly believe that there is significant variation in town," Johnson agreed.

But hospitals do not freely advertise those variations. The structure of the system is such, officials say, that the burden to understand costs lies with each patient.

TO SHOP OR NOT

If the chargemaster data isn't exactly applicable, and if insurance contracts are private, can consumers still shop for a procedure?

In most cases, patients just don't -- or can't -- consider that option. They're not worried about prices because they have insurance. Or they're following their doctor. Or they just had a heart attack.

"You're in no position to bargain in those silly nightgowns," said Bonnyman. "You're not going to get up, walk into the lobby and out the door and go somewhere else."

That's why, he said, coming up with a formula for consumers to shop with isn't realistic under the current system. What health care really needs to become more consumer-friendly, he said, is new definitions of charges, costs and, crucially, value.

"The new health care law has gotten precious little respect from many people in Tennessee, but very technical aspects have a huge potential to improve the system in ways that consumers really can't do for themselves," he said. "It seeks to shift the payment system from 'a la carte' to pay structures based on outcomes and quality of care."

Sadro said the Affordable Care Act is going to change "everything" about hospital pricing and payments. Some provisions of the act already have taken hold, with a key feature -- public access to a health insurance marketplace -- scheduled to begin in January 2014. However, it could take years before some of the law's effects fully are felt.

But while the political battles over health care reform rage and industry leaders struggle to interpret the law, what can patients do themselves to try to save money?

"Patients are becoming more and more informed consumers, and they should ask what a procedure is going to cost," Sadro said.

Many patients simply don't know how to ask about costs, said Johnson.

"Don't ask the hospital for their average charge for a procedure," he advised uninsured patients. "Instead, always ask what your discounted price would be for a self-paying patient for this procedure. If you're insured, ask 'What am I going to owe based on my benefits plan?'"

Insurers have also created more online tools to give members a range of in-network prices.

Bonnyman cautions that it is still very hard or impossible for consumers to make comparisons specific to their circumstances. And hospital estimates are nonbinding.

Carr is glad she shopped for a procedure, but doesn't think it should have been so complicated. She is not a fan of Obamacare, she says, but she does believe that the system should be reworked.

"It just can't stay the way it is," she says. "Something has got to change."

Contact staff writer Kate Harrison at kharrison@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6673.