GPS teacher responsible for state's top rank for female students in AP computer science classes

Monday, February 24, 2014

THE TESTAccording to Collegeboard.org, the Advanced Placement Computer Science test lasts three hours and includes a 40-question multiple-choice section and a four-question free-response section. Both of these require students to "demonstrate their ability to design, write, analyze and document programs and subprograms."

A handful of people making a difference on a grand scale is usually the kind of plot twist reserved for the silver screen, but last year, one local teacher and a few dozen students helped buck a national trend.

Every year, high school students conclude their Advanced Placement college equivalency courses with a rigorous multi-hour exam. Those who pass receive college credit in the relevant subject, giving them a pre-graduation head start.

For years, AP Computer Science courses might as well have been gentleman's clubs, where boys have outnumbered girls by more than four to one, on average. According to statistics from the College Board, the national association that oversees AP courses, girls accounted for only 18.6 percent of the 30,000 students who took the AP Computer Science test last year.

In Tennessee, however, it was a different story. Of the 251 students who took the exam in 2013, 73 were girls. At about 29 percent, that was the highest rate in the country, according to the College Board.

That the state's percentage should be so high is largely due to the 30 students in Jill Pala's computer science classes at Girls Preparatory School, without whom the rate would have been closer to 19 percent, just above the national average.

RANKINGSAccording to an analysis of testing data released in 2013 by the College Board, the following states had the highest percentage of female students take the Advanced Placement Computer Science Test in 2013:1. Tennessee - 29.1 percent (73 of 251 students)2. Arkansas - 27.7 percent (48 of 173 students)3. Texas - 22.9 percent (910 of 3,979 students)4. California - 21.6 percent (1,074 of 4,964 students)5. South Carolina - 20.7 percent (57 of 275 students)6. New York - 20.2 percent (377 of 1,858 students)7. Florida - 20.1 percent (306 of 1,521 students)8. Maryland - 19.8 percent (323 of 1,629 students)9. Virginia - 18.6 percent (308 of 1,655 students)10. Georgia - 18.2 percent (229 of 1,261 students)National average - 18.6 percent (5,485 of 29,555 students)Source: Barbara Ericson, director of computing outreach for the Institute for Computing Education at Georgia Tech's College of Computing.

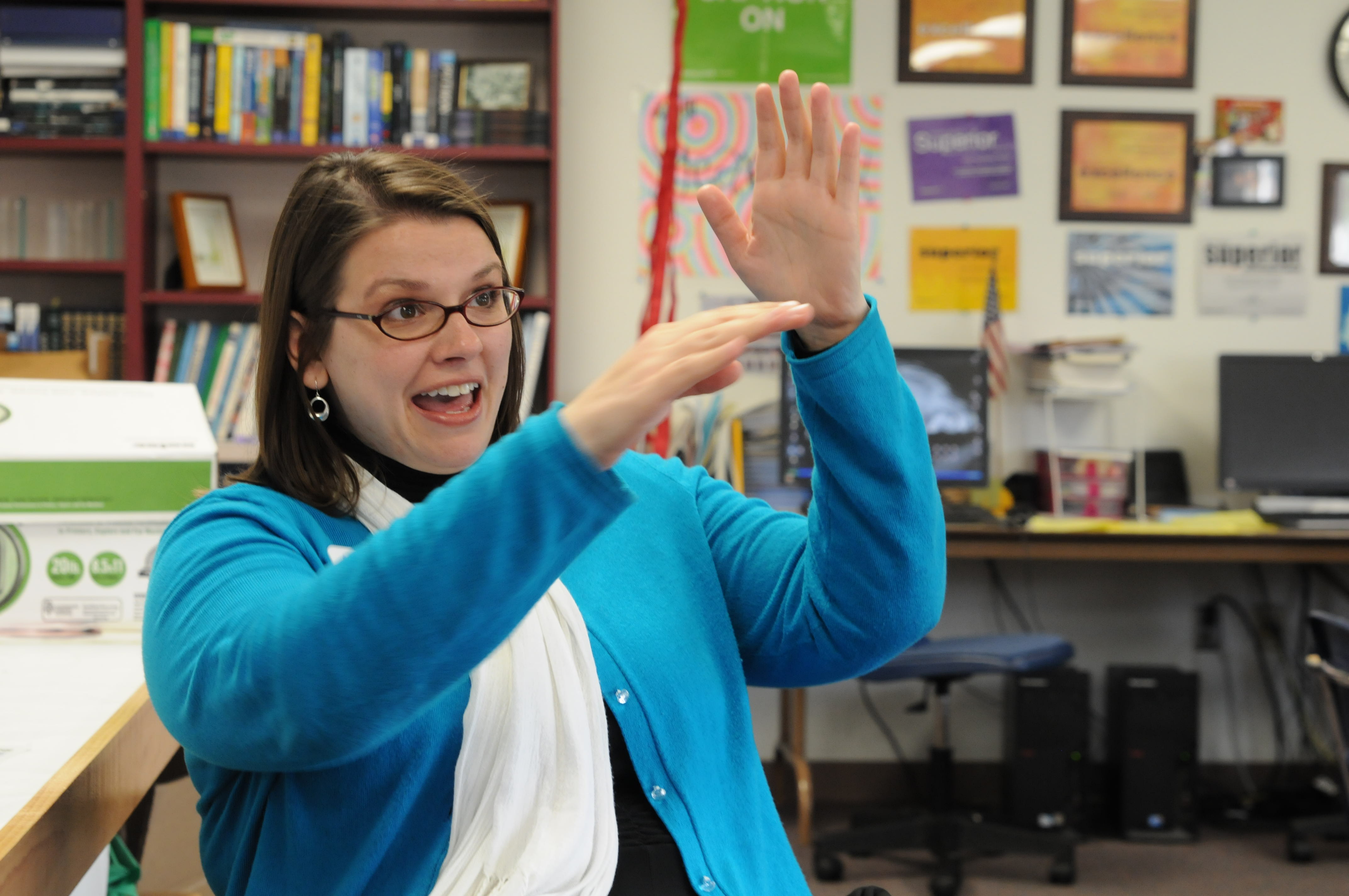

"That inspires me to keep working hard with the girls," Pala says while seated at a desk in her classroom. Behind her, a quartet of white Frisbees emblazoned with the logo of her alma mater, Xavier University, hang above white boards covered with notes and samples of programming code. A nearby bookshelf is filled with books on the Java programming language upon which the AP exam is based.

"[Those statistics] make me appreciate the fact that, because I have this class here and girls take it, all of a sudden we made Tennessee make some news about it," she adds. "There are a lot of times when people say, 'Can one person really make a difference?' Well, here's an example where we did, one school."

A DOUBLE-EDGED SWORD

That one school - one class - can be so decisive, however, is a worrisome indicator of the state of computer science education in Tennessee, says researcher Barbara Ericson.

The director of computing outreach in the Institute of Computing Education at Georgia Tech, Ericson releases participation statistics for the AP exam every year. Her study is how Pala discovered that her students accounted for 40 percent of all girls in Tennessee who signed up for last year's exam.

With 30 participants, Pala's class was well above the national average of 22.6 students per teacher who took the AP exam, according to the report. In a perfect world, though, she wouldn't have been so influential, even with such high numbers, Ericson says.

"It's great that she has an impact, but it's terrible that the numbers are so small that she has an impact; 250 students isn't that many," Ericson says.

Pala, 34, worked in software development in the private sector after graduating from Xavier in 2001. She was hired in 2006 as GPS' sole full-time computer science instructor. Being chosen by the school was a kind of homecoming for Pala, who was a student at GPS and graduated in 1997.

During her time there, Pala says the closest GPS came to offering computer science education was a handful of computers in the science building and library that were intended to serve the whole school. The most complicated computing task she was asked to tackle before graduating was to scan an image and manipulate it for a project in her physics class.

Since being hired, Pala has focused her efforts on disabusing GPS students that computer science is a boy's game and to encourage them to enroll in her AP course, which is offered for students in grades 10 to 12.

Pala's enthusiasm for computer science and her efforts to encourage students to cross the gender line have made her a valuable asset in building support for the program, says Sue Groesbeck, GPS's interim head of school.

"I can't think of any other school - coed, girls or boys - where there are two full classes of AP computer science," Groesbeck says. "It is one of our most popular AP courses. Our numbers are an anomaly because Ms. Pala makes the learning so incredibly valuable and fun."

The current enthusiasm for the computer science program is a relatively recent development. Participation in the course was minimal until 2010, when Pala received permission from GPS administration to begin actively recruiting students who exhibited a flair for relevant subjects such as science and math.

"I target the girls in the honors language classes, too," Pala explains. "[Programming] is about language, because you're learning to translate your ideas from English and translate them into something a computer can understand."

In the 2010-11 school year, the year before she began her recruitment campaign, she had three students. Her largest class to that point had a roll call of nine. Once she began sending out letters to prospective girls, however, 18 students signed up.

One of her earliest recruits was Meghna Talluri, 17, who enrolled in Pala's class as a sophomore. She says she plans to study some form of engineering in college, and computer science seemed like a natural inroad.

Even if her career path hadn't been so in line with computer science, however, Meghna says she learned valuable skills from Pala's course that would be applicable to a wide variety of fields.

"One thing I've learned from this class is how to think logically," she says. "That's a skill everyone should have, regardless of gender."

BLAZING A TRAIL

Although her efforts have swelled interest in computer science at GPS, Pala says she's committed to ensuring that her school doesn't remain a statistical outlier.

Last fall, she was nominated for and ultimately selected as one of 13 educators and industry professionals in the country to take part in the inaugural session of Trailblazer, an international computer science education program founded by Google. The goal of the program was to develop proposals for outreach programs to expand interest and participation in computer science programs globally.

Pala mentored a group of Trailblazer students and collaborated - primarily via web conferences - with other program Trailblazer fellows in North America and overseas. Several magnets with Google logos dot her classroom's whiteboards like safari trophies.

She says she hopes to take the ideas and inspiration she received as a Trailblazer fellow and apply it to local computer education outreach efforts. Last December, she and several GPS students went to the Chattanooga Public Library to participate in the Hour of Code, an event designed to promote computer science and to teach basic programming skills to middle schoolers.

The quest to introduce more students to computer science isn't motivated solely by a desire for greater diversity in the field. The paycheck is a pretty compelling carrot, too, Pala says.

According to its most recent Employment Outlook report, the Department of Labor's Bureau of Labor Statistics projects that computer and mathematical occupations will add 778,000 new jobs this decade at an average salary of $60,670. The largest growth in this class is expected to be software developers, for whom 143,800 new positions will be available.

Given that it will be a foundation skill for one of the country's fastest growing and most lucrative job markets, it's imperative that computer science be emphasized more strongly, says Pala, who is actively campaigning at GPS to convert the course from an elective to a graduation requirement.

"It's something I would love to see for every student in Chattanooga, not just GPS," she says. "When I make the argument for teaching computer science, it's not just because I'm trying to prepare these kids to go off to Silicon Valley or New York or Boston. These tech jobs are going to be here."

Contact Casey Phillips at cphillips@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6205. Follow him on Twitter at @PhillipsCTFP.