See regional commute times in an interactive map.

View moreSee an interactive map of regional commute times at timesfreepress.com/commute.

Moe Songy, vice president of operations at the Chattanooga Airport, enjoys grabbing a bite to eat in Chattanooga at Flying Squirrel, shopping on Brainerd Road and attending the Riverbend festival.

But the transplanted Cajun doesn't live in Hamilton County, or even in Tennessee. Instead, he drives 23 miles to work every day from Tunnel Hill, Ga., located on the border between Catoosa and Whitfield counties.

Songy and his wife are among thousands in the Chattanooga region who wake up every day, hop in the car and drive to another county or state to work or learn.

John Sweet, proprietor of Niedlov's, drives to work from a farm in Rossville. Jim Volmering is known for flying in from Arizona to work at Adtech Ceramics on Manufacturers Road. A handful of attorneys at the Chambliss, Bahner and Stophel law firm drive more than 100 miles round trip to the firm's Chattanooga offices.

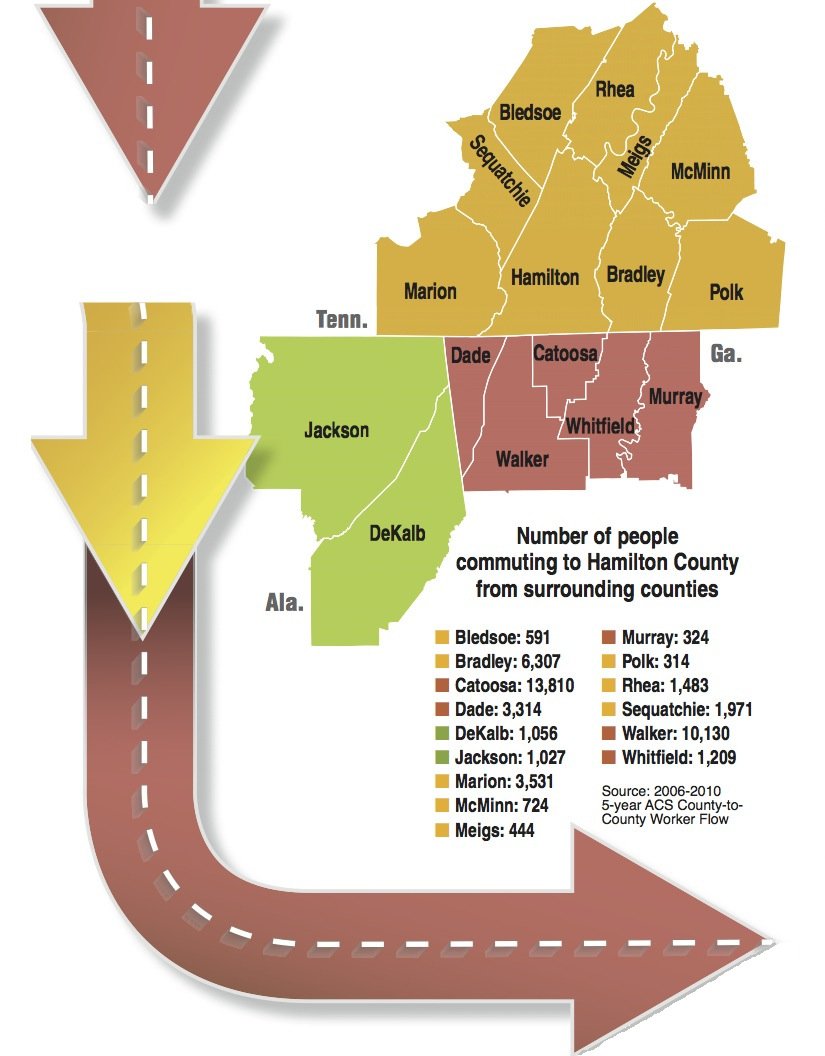

Unwilling to take on higher living costs and a substandard education system in exchange for the convenience of living closer to what experts call the "jobs basket" in Hamilton County, more than 27,000 residents in the Catoosa, Dade and Walker counties travel to Hamilton County for work each day, far more than the 22,000 in three Georgia counties closest to Chattanooga who have a local job.

In total, more than 51,000 of Hamilton County's estimated 193,000 workers come from elsewhere, according to the Census.

"We knew what we wanted, we wanted a little bit of acreage, we have big dogs and we wanted them to have room," Songy said. "For the money, we got more home and more land in Tunnel Hill, so we bought a house with six acres and a wooden picket fence."

Hamilton County is literally surrounded by bedroom communities like Tunnel Hill, as measured by the ratio of jobs within each county compared to the number of workers. Bledsoe, Polk, Sequatchie, Meigs and Dade each have two workers for each job, meaning that more than half of the workforce commutes elsewhere, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

Compare that with manufacturing-laden Whitfield County in Georgia, and Hamilton County in Tennessee, which each have more jobs available within the county borders than they have workers to fill them.

"It would be beneficial for Hamilton County from that standpoint, because you're going to generate more tax revenue off commercial and industrial property than you do off a residential property," said Bridgett Massengill, project manager for Thrive 2055.

Bedroom communities like Catoosa County, though they are desirable places to live, to a certain extent help subsidize industrial counties like Hamilton County, Massengill said.

That's because for governments, it generally costs more to provide services to neighborhoods than those communities generate in tax revenue, while industrial and commercial developments generally pay more in tax revenue than they cost taxpayers in terms of services.

In other words, Catoosa County is doing Hamilton County a favor by housing 13,810 of its workers, as measured by the American Community Survey.

"That's your typical definition of a bedroom community," Massengill said. "We are expecting Catoosa to have the highest amount of household growth, but does that also mean they'll have the job growth?"

Jobs are often the primary reason for a long commute.

Take Lacy James, hair stylist for Great Clips at Northgate Mall. James commutes to Chattanooga from Gruetli-Laager, Tenn., in Grundy County. That's a drive of about an hour and 15 minutes across two time zones, requiring her to wake up at 5 a.m. central time in order to arrive at work by 9 a.m. eastern, she said.

"I do get aggravated with it sometimes, but as hard as it is to get a job, it's better to have a job," she said.

She's already burned through one car and has purchased a 40 mile-per-gallon Nissan Sentra replacement which, through gas refills and oil changes, consumes about one third of her income, she estimated.

"Just having a job where I actually get along with everybody there, it's worth it to make the drive," she said.

She'd love to be in the same time zone where she works, but housing prices in Hamilton County have given her pause. One of the cheapest homes she found in Red Bank cost $300 per month to rent, while a three-bedroom home in Grundy County can be had for $450 per month, she said.

But there are some positives to the hours of driving back and forth across East Tennessee. She has plenty of time to listen to music, and, "If I've had a bad day at work, then by the time I come back home I've wound myself down so it's not affecting household."

In the six-county Chattanooga metropolitan area. the census bureau estimates 1.926 workers, or 1.5 percent of the labor force, have daily commute times like James of more than 90 minutes.

Though more than 5,000 workers commute from outlying areas into Hamilton County, many workers are moving into the city to avoid needing a car at all.

In fact, of 460,000 workers tracked over a five-year period in the 16 counties surrounding Chattanooga, the vast majority -- 312,000 -- commute within the same county, according to the American Community Survey.

In Hamilton County, 142,000 of its estimated 155,000 workers commute within the county's borders. Some stretch the traditional definition of a commute.

Lucky Ramsey, director of recruitment for the Lamp Post Group's Waypaver subsidiary, shares a single car with her husband. It's a 1996 Saab with 310,000 miles on it, though it's getting used less and less now that the couple moved to Chattanooga's Southside.

"We use the Chattanooga bikes," she said, referring to the city's publicly-available rental bikes available at kiosks across the downtown area.

"I walk two blocks to pick up a bike, it's actually on my way to work. Then I drop it off on the corner of M.L. King Boulevard and Market Street," she said.

It's a flat fee per year, typically around $75, but Ramsey got a discount and secured a membership of $50. For Ramsey, it's not just about saving money. Riding a bike to work is a whole new way of life, she said.

"When you get in the car, there's a certain rush mentality," she said. "But when you're walking, you just go where you're headed."

Contact staff writer Ellis Smith at 423-757-6315 or esmith@timesfreepress.com with tips and documents.