A life, a death, a mystery: Police say Jennifer killed herself, but there might be another story

Sunday, March 23, 2014

Daniel Beshears told investigating Bradley County officers he was pulling clothes from the dryer when Jennifer came in the laundry room, grabbed the gun from the top of the washer and shot herself in the head. But the washer and dryer top as well as the wall and window blinds behind showed no sign of blood except where Beshears said he picked the gun up from the floor and laid it on the washer.

Daniel Beshears told investigating Bradley County officers he was pulling clothes from the dryer when Jennifer came in the laundry room, grabbed the gun from the top of the washer and shot herself in the head. But the washer and dryer top as well as the wall and window blinds behind showed no sign of blood except where Beshears said he picked the gun up from the floor and laid it on the washer.HOW WE DID ITThis story is based on numerous interviews with Jennifer's friends, clients and neighbors; on the investigative file developed by the Bradley County Sheriff's Office using sources such as cellphone and bank records, autopsy reports, video and audio of interviews and officers' radio communication logs; and internal Cleveland Police Department files. Some sources' last names were withheld to preserve their privacy or to protect the minor child.

Editor's note: Footnotes are included in italics/parentheses throughout the story.

The first thing the neighbors heard was the throaty roar of a motorcycle racing away in the night.

Then the sirens. One. Two. More, until the dark, narrow street was lined with police cruisers and a pair of ambulances, blue and white lights stuttering.

Neighbors watched Bradley County investigators string crime scene tape around Jennifer's small, white frame house.

They saw people carrying equipment through the open front door, the pop of camera strobes behind the curtains - living room, bedroom, kitchen. Others lugged boxes out of the house and packed them into patrol cars.

All night, they sat watching. A man wearing an orange jail jumpsuit and flip-flops arrived in the back of a patrol car. Deputies walked him into Jennifer's house and then back out a few minutes later.

After the sun came up, after the yellow school bus hauled the neighborhood kids off for the day, the long, dark bag was wheeled out on a gurney, placed in a truck and taken away.

The ambulances and patrol cars drove off. Only the fluttering crime scene tape showed something had happened in the house off Georgetown Road.

After that, nothing.

Nothing on television or in the paper saying what had happened that chilly night of March 14, 2013. No obituary or funeral announcement by a grieving family.

Jennifer was gone. And no one may ever know why.

(Interviews with five neighbors; Bradley County dispatch radio communications logs)

She was stop-in-the-street-and-stare beautiful: huge brown eyes, a luxurious fall of chestnut hair, tantalizing curves and broad, enticing smile. Men and women called her warm, playful, dynamic, fascinating.

Those assets were key to Jennifer's business: selling herself.

The 41-year-old mom with a little girl in a local elementary school didn't live like her suburban neighbors - she walked on the wild side.

The polite term is "escort."

(Jennifer's cellphone records, interviews)

Jennifer believed in the adage, "follow the money."

No street corners or fleabag hotel rooms for her; she liked linens and luxury. Her Facebook cover photo showed her posed in a black dress and pearls by a high-dollar Jaguar XJ that a friend said was bought for her.

The men who could afford her for $500 an hour or a $5,000 weekend included businessmen, at least one professional athlete, lawyers and doctors.

(Client roster obtained from Bradley County Sheriff's Office)

One client, Burt, said she lived for a couple of years with a prominent Charleston, S.C., drug dealer in his $2 million oceanfront mansion.

Eventually the dealer was busted with "a significant amount of money - $700,000 to $800,000 - and God knows how much drugs," said Burt, who also was living in Charleston at the time.

Jennifer was there when the raid went down, Burt said, but she had a longstanding habit of cultivating cops and it paid off for her.

When agents came after the drug dealer, "somehow somebody was looking out for her," Burt said. "She came downstairs and talked to one guy on the side; he told her to get lost."

Jennifer kept that handy habit when she moved to Bradley County in 2010. She dropped hints that a "SWAT buddy" kept an eye on her, and she had a photo on her phone of a Bradley County deputy in her living room, shaking hands with her little girl.

None of those connections stood up for her, though, when a bullet shattered her head that March night. It took just minutes for her death to be labeled a suicide. In the days to come, Bradley County investigators apparently didn't consider evidence suggesting she hadn't pulled the trigger.

(Bradley dispatch records)

Though her family's roots are in Bradley County, Jennifer was raised by her divorced mother in Jacksonville, Fla. Her mother died in 1998, at only 49. Jennifer told some people it was cancer; others, a drug overdose. Jennifer was 20.

(Interviews, Florida Times Union obituary)

She told people she never graduated from high school - her landlady, Renee Leach, remembers Jennifer having her daughter read a notice for her - and she apparently never held a regular job for very long.

But whatever she lacked in book-learning, Jennifer knew a lot about men - especially how to get close to the ones with money.

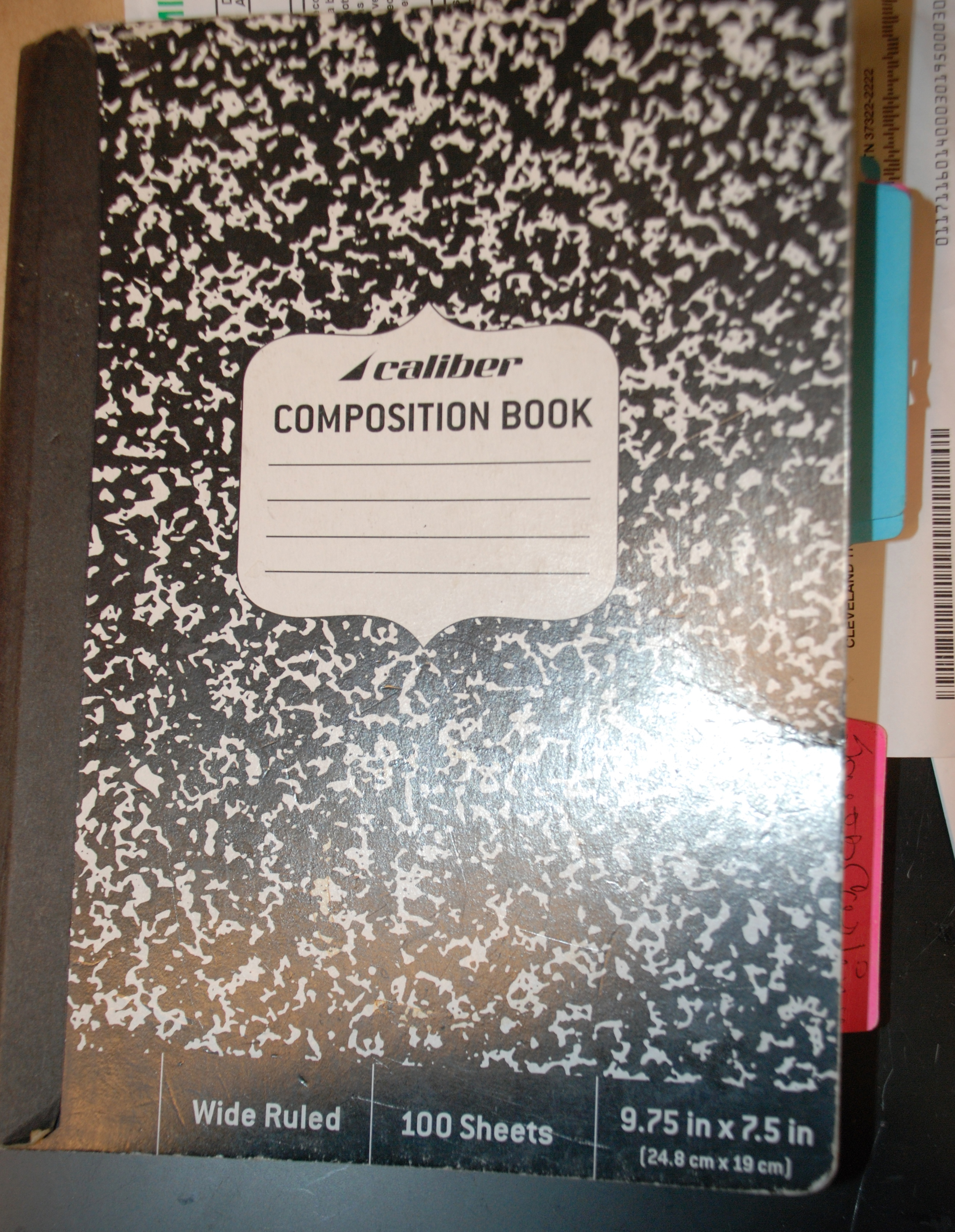

She kept their names - nearly 90 of them -and phone numbers in an old-fashioned, cardboard-covered composition book with a black-and-white marbled cover. Some names have jotted notes: "Funny." "PGA." "Nice." "$$$$$."

Like any businesswoman, she advertised, striking sexy poses in ads on websites like eros.com and preferred411.com under the name "Geonnifox." Her business card read "Snootywhirl."

(Cellphone records, Internet search, interviews)

She snapped selfies by the dozens, smiling in front of a showplace home, from the back of a tricked-out bike, in luxury suites or beachside resorts, always with a man close by and sometimes her daughter as well.

A local friend, Alan, said it was mostly because of the little girl that Jennifer decided to move closer to her family in Bradley County. The grandmother she loved - the one person in her family who didn't judge her, the landlady said - was ill, too, and Jennifer wanted to help take care of her.

She moved into the little house off Georgetown Road in November 2010, Leach said. She paid cash up front for the first six months' rent.

But she was gone a lot, sometimes leaving her little girl with a nanny for days at a time while she traveled to Jacksonville, Charleston and West Virginia to meet clients. She worked closer to home, too - a whole section of her trick book listed clients in Southeast Tennessee, North Georgia and Alabama.

She dropped names of prominent people she claimed she'd dated. Alan said he was driving her past a local motel one day when she said, "You'll never know how much money I made in that place."

In fact, the money was a problem. She couldn't deposit her illegal cash earnings in a bank because, without a job, she had no way to explain the income.

She told Leach she kept her money in safety deposit boxes, putting just enough in the bank each month to cover her rent, utilities and other basics.

Expensive furniture, rugs and decorations filled the little house. Leach worried that the weight of Jennifer's heavy couches, tables, chairs and beds would damage the floors and walls.

She lavished herself in jewels and stored five full-length furs in a locked closet.

(Sheriff's office photos, interviews)

"Jennifer was an attractive, captivating lady," said Layne, a local businessman who dated her off and on for a couple of years and treated her to a trip to Las Vegas.

But she was also temperamental and erratic. Another client, George, who dated her for about two years, remembered her going into rages and throwing things.

"She lied too much," he said. "You couldn't believe anything she said."

She broke dates and promises, got in trouble for letting her little girl skip school, couldn't remember to pay her rent on time.

Alan said she'd told him she wanted to get out of the life of a call girl and get a straight job. He helped her take her profiles off eros.com and other online sex sites.

(Interview)

"The past year she'd been getting out of everything. She wanted to go back to school, get into college, try to be right. Her daughter was growing up and she needed to be more of a mother figure, be there with her and do things with her," Alan said.

That's what she told him, anyway.

Other people who knew her might have warned him that Jennifer told people whatever she thought would profit her the most.

On a single day - March 11, 2013 - she told three men that each was her one and only love.

Layne was one. He paid for a lawyer when she said she might be sent to jail because her child had missed too much school. He was giving her money for groceries and utilities and a set of tires.

"I love you soooo much!" she texted him.

She had told George, who lived in West Virginia, she was pregnant with twins by him. She told him she couldn't work. He gave her thousands of dollars - for baby needs, for court fines, to keep the lights on - and begged her to come live with him. That day, she wrote: "I love y come back talk listen learn love trust marriage together forever us as a unit."

She didn't tell him she'd had an abortion three days after Christmas. Even into March, she was still asking him for money for the coming babies, while she told people around her she'd miscarried after a fall on the stairs.

The third wasn't a client. In fact, her friends and landlady weren't sure who "Daniel" was or why he'd started showing up at Jennifer's little house.

He wasn't rich or polished. He was local; he wore scruffy clothes and used gutter language.

She told her landlady and others he was working for her, watching her little girl. She said he was a gay man, in a relationship.

But her text to Daniel - James Daniel Beshears, of Cleveland - March 11 said, "Thank you for changing my life I really am in love for the first time in my life."

(Cellphone records)

It was a bullet from his gun that took Jennifer's life three days later.

(Sheriff's investigative file)

Jennifer didn't stop working. She kept making out-of-town trips, coming home and putting cash - $900, $1,000, $1,500 - in her BB&T bank account.

But the money was going out faster than it came in. She might pull $500 or $1,000 out of her account in three or four days, always in cash, and paid hundreds of dollars in overdraft fees.

(Bank records in sheriff's investigative file)

She began acting fearful, installing padlocks, an alarm system and security cameras in the house. She complained to Leach that she and her child were getting sick from gunk in the air-conditioning ducts, and she taped over the vents.

(Interview, cellphone records)

Some of her friends and clients wondered about drugs. She told Leach she used Adderall, a stimulant used to treat hyperactivity disorder. George said she had smoked crack and used other drugs when they were together.

Neighbors began seeing a guy who rode a motorcycle spending time at Jennifer's place. She called him her "SWAT buddy." He was Bill Higdon, who was on the Cleveland Police Department Special Response Team.

(Interviews, cellphone records)

Higdon was one of four Cleveland cops who were hauled in by supervisors and counseled in 2008 after rumors that some officers were giving pills and alcohol to teenage girls in exchange for sex, looking at porn on department cellphones and fleeing police in other jurisdictions.

(Times Free Press archives)

He and Jennifer had begun swapping texts and photos in late August 2012. Some -including explicit pictures - hinted that the relationship was more than electronic.

On Dec. 12, 2012, Higdon texted her his address and asked, "U gonna come see me tonight and relieve tension?"

In January, when Jennifer was worried about going to jail, she asked her "SWAT buddy" for a favor.

"Do y have a way to look up Warents [warrants] that would suck we would not be able to date ..." she texted.

"I wouldn't arrest u," he texted back. Then, "You don't have one [arrest warrant.]"

They were still exchanging texts in March. One of Jennifer's last acts was to text a photo of Higdon to her landlady, Leach.

"What do u think? He's nice pretty much changed my life so tell me what you think" read the message she sent Leach just hours before she died.

The first texts between Jennifer and Beshears began at the start of February 2013.

He worked at a pallet company, talked about having served in Iraq. Soon he was spending time at her house and she went sometimes to his apartment.

(Cellphone records, videotaped interview at sheriff's office)

Neighbors noticed another guy visiting when Beshears was at Jennifer's house. Sometimes he came on a motorcycle, sometimes in a Cadillac. It wasn't Higdon, but nobody knew who he was. Neighbors wondered if he were a drug dealer, maybe, or an undercover cop.

Before the end of February, Beshears texted to Jennifer, "When are y going to marry me?"

But they fought - over his friends, over hints he was involved in illegal activity, and especially when she found out he'd had sex with another woman.

"I am sickened and I never want to see you again I can't believe y broke our bond," Jennifer texted March 6. Followed by, "I have to get use to y not being in my life ... I am sorry it's better this way don't contact me any more ..."

Beshears' reply was angry. "Have a little respect or faith in me I'm your man and you know it."

Moments later, he added, "you don't ever [expletive deleted] darken my doorstep again."

But then he cooled down and changed the subject.

"Hi I thought you're going to make a meds [buy] this morning ... u said you were getting drox [oxycodone] and xanys [Xanax] ... it don't matter tho I'll get me some after work."

Twenty-four hours later they were fighting again by text.

"I don't like being alone so I will have someone here sorry," Jennifer wrote.

"You don't care about how yoi [sic] hurt everyone else," Beshears responded. "It's just what you want can't even let the bed get cold huh."

(Cellphone records)

They were still fighting on the Thursday night that Jennifer died.

She was at her lawyer's office over the truancy case late that afternoon. That's when she texted the Higdon photo to Leach.

(Beshears' statement to investigators, cellphone records, interview)

The landlady, who said she had had enough of Jennifer's erratic behavior, went by the house and delivered a 30-day eviction notice around 9 p.m. She said Jennifer didn't appear intoxicated.

(Interview)

But the eviction notice sent Jennifer into a tailspin. She churned out texts - two in five minutes to George in West Virginia - just "911" with a cellphone photo of the eviction notice. She texted Layne, saying to call right away, and sent a string of messages to Beshears.

He wasn't receptive.

"You know what I'm tired of this" he wrote in a profanity-laced text at 9:16. "... don't ever call me or text me again."

She sent him six texts between 9:23 and 9:32 p.m. asking him to come to the house.

" ... I need your skin w mine tonight I love y I've waited along [sic] time for y come home," Jennifer wrote.

Beshears made a 911 call to Bradley dispatch at 11:36 that night.

At 11:47, a patrol lieutenant reported back to dispatch from the house off Georgetown Road that a woman was dead, shot in the head. The radio log read: "Apparent suicide attempt."

The first detective didn't arrive for another half-hour, but the direction of the investigation was already set.

(Dispatch radio logs)

Investigators walking through the front door could see smears of blood around the knob and latch on the interior side of the door. Jennifer's big purse lay on a dining table just ahead, next to a 20-ounce Sprite bottle about a quarter full of bourbon. In the kitchen to the left, an aluminum can of Twisted Tea, a malt beverage, was marked by more bloody smears. Two drops of blood dotted the front edge of the stove.

Farther along the kitchen, a curtain covered part of the entrance to the laundry room.

A woman's body was visible in the opening. She was seated, leaning against a plastic utility cart to the left of the door, braced behind by the leg of a clothing rack. Her head slumped forward and blood coated her right front, arm and hand. More blood - lots of blood, thick purple-red, drying to crusted black - pooled around her body. Drops trailed down the side of a white washing machine beyond the sink. More drips and smears, along with bloody shoe prints, were on the floor in front of the washer, on the left beyond a utility sink.

Atop the washer lay a 9 mm semiautomatic pistol beside a single smear of blood. A brass cartridge lay on the frame of the sink, left of the faucet.

A single bullet hole pierced the ceiling about two feet inside the room. A couple of faint blood spots stained the Sheetrock a few inches away.

(Photos from sheriff's office investigation)

Officers brought Beshears to the Bradley County Justice Center to ask him what happened.

Sobbing, nearly hysterical and obviously intoxicated, Daniel told Detective Dewayne Scoggins he'd gotten to Jennifer's house about 9 p.m. to find Jennifer in the bathroom, high and wild on methamphetamine and vodka.

Beshears said Jennifer raged around the house, yelling and crying that she wanted to go to her mother, who he knew was dead. She pulled one of the carved finials from the mahogany four-poster in the bedroom and swung it around wildly, he said. Evidence photos show the piece, about the size of a bowling pin, lying on the bedroom carpet.

(Videotaped interview from sheriff's investigation file)

Officers found an Absolut vodka bottle on the bathroom counter next to a partly used bottle of dark brown hair dye. A glove like those used in home dye kits floated in the full bathtub.

A glass drug pipe, dark with residue, lay in a trash can by the toilet. A small Baggie lay on a table just outside the bedroom door.

On the mirror over the sink was a message, scrawled in Jennifer's loopy writing in some white substance: "Forgive me God, Forgive me, I coming home, let me come home."

(Sheriff's office photos)

Beshears said he was afraid she would hurt herself. When he couldn't get her to calm down, he decided to take the child to his apartment for the night.

He said he retrieved his gun from under the mattress and walked into the laundry room. He'd placed the weapon on the washer and was leaning over the dryer when Jennifer came swiftly in behind him.

"I turned to pick up my [clothes], she grabs that pistol with her left hand ..."

"Was she left-handed?" Scoggins interrupted.

"No," Beshears said. "Bam! She killed herself in front of me and that baby ... blowed [expletive deleted] blood all over me."

He said he picked her up, checking for signs of life, and lifted the pistol from the floor to the top of the washing machine.

(Videotaped interview)

An autopsy report from the state medical examiner's office in Knoxville said the 9 mm bullet entered her neck behind and below her left ear, passed through her brain and exited the top right of her skull. Her blood alcohol level was 0.10, slightly above the legal limit, and she had methamphetamine and its metabolized product, amphetamine, in her blood.

(Autopsy report, Knox County Medical Examiner)

Beshears said he and Jennifer had known each other for a few months and had been engaged for two or three weeks. He was fine with how she earned her living, he told Scoggins: Sex and love are two different things.

And the money was good, he said. Jennifer had earned $150,000 in the last year. He wouldn't give permission for investigators to search the house - he was worried that they would seize what he said was more than $120,000 in jewels stashed in a closet.

"The woman was a swindler," he said. "When she hooked up she got everything she could. She was good at her job."

But his description of the shooting is different from what photos and cellphone evidence show.

It's possible his memory was unclear: He told Scoggins he'd taken five hydrocodone pills that day along with three 24-ounce Twisted Teas and whatever bourbon was missing out of the 20-oz. Sprite bottle on the dining room table.

(Videotaped interview)

Among the inconsistencies:

- Beshears told Scoggins he got there about 9 p.m. but Jennifer's phone records show she was still texting him after 9:30.

- He said he laid the gun on the washer and that Jennifer came in beside him as he stood at the dryer, grabbed the gun and instantly shot herself, spattering him with blood.

But the white enamel tops of the washer and dryer were clean except for a single smear where Beshears said he laid the gun. The photos don't show blood on the white blinds over the window behind the washer or the ceiling above where the dryer nestled in the corner.

The blood on the washing machine is inches from the floor, on the side next to the utility sink and on the lower front corner. The largest area of blood was around Jennifer's body, closer to the door.

- As manufactured, the SCCY 9 mm has a nine-pound trigger pull. If she fired immediately, there would have to be a round in the chamber and the safety switched off. And Jennifer would have had to hold the gun at a severe angle in her off hand to produce the bullet track.

- The hole in the ceiling was in the opposite direction from the path the bullet would have traveled had Jennifer been facing the washer and dryer when she pulled the trigger, as Beshears said.

- The little girl, who was there, told investigators she believed the gun was already in the laundry room. She heard her mother and Beshears arguing over a gun. And she said Jennifer went in the laundry room first and Beshears followed her.

So the investigators had plenty to work with: potential fingerprint evidence; ballistic evidence from the gun, the cartridge and the bullet; cellphone records and Beshears' admission that he was on pills and alcohol that night. The bloody shoeprints in the floor. The neighbors' recollection of hearing a motorcycle roaring away just before the sirens began.

(Videotaped interview, sheriff's office photos, summary of interview with child contained in sheriff's file)

They made no use of any of it.

The Bradley County coroner ruled the death a suicide after the toxicology tests came back in September showing Jennifer had alcohol and meth in her bloodstream.

A Sept. 9, 2013, report written by Detective Brandon Edwards of the Bradley sheriff's criminal investigation division said: "The statements, physical evidence and autopsy reports support suicide."

The report noted that the child, interviewed the next day, told a detective she'd heard her mom talking that night about going to see her own mother. That wasn't mentioned in the two-page summary of the girl's interview provided to the Times Free Press.

The report also said Beshears passed a polygraph test given by a Tennessee Bureau of Investigation agent March 22, 2013.

•••

Bradley County Attorney Crystal Freiberg was the liaison for the sheriff's office when the newspaper requested the investigative file on the case in October.

The file given the newspaper didn't include forensic evidence. After relaying several requests to the sheriff's office for the data, Freiberg said the sheriff's office told her there wasn't any.

The investigators didn't provide any evidence they fingerprinted the scene - the gun, the liquor bottles, the blood-smeared Twisted Tea can, the drug pipe and Baggie, the washer/dryer - or Beshears.

The bullet was never recovered for testing. There was no ballistics report to prove that the fatal shot came from the gun on the washer.

There were no results from blood tests to check if Beshears had used any drugs other than the hydrocodone and alcohol he admitted to, or how intoxicated he was.

Investigators secured Beshears' clothing and swabbed his hands for gunshot residue - they gave him an orange jail jumpsuit to wear, then took him back to the house where investigators were still working to get some clothes - but neither his nor Jennifer's hands or clothes were actually tested.

Freiberg said the detectives explained it to her this way: The TBI crime lab is badly backed up, so it won't do tests that aren't needed.

The investigators knew Beshears' hands would show residue because he told them he picked up the gun. And they knew Jennifer's hands would carry the residue because he told them she shot herself.

The Bradley County Sheriff's Office declined requests to interview Edwards or anyone in administration about the investigation. Sheriff Jim Ruth did not respond to a separate request for comment on the case.

Beshears didn't respond to texts and voicemails on his cellphone.

When Higdon's picture turned up on the landlady's phone, Bradley detectives interviewed him. He denied any sexual relationship with Jennifer and said he didn't know she was a prostitute.

(Audio of interview from sheriff's investigative file)

In May 2013, Higdon was fired from the Cleveland department. The reason given was that he needlessly ran his police cruiser into a pool of water and ruined the engine. It was the fifth or sixth cruiser he'd wrecked since he joined the department in 2006, his personnel file shows.

(Higdon personnel file from Cleveland Police Department)

Higdon didn't respond to texts or voicemails left on his cellphone. The Peace Officer Standards and Training Commission said he doesn't appear to be working in law enforcement in Tennessee.

A retired Chattanooga police detective who has investigated more than 400 deaths agreed to review the file on Jennifer's death for the Times Free Press.

Mike Mathis, who retired as the head of Chattanooga's major crimes division and is now a consultant, wouldn't comment on the specifics of the file, saying there are many ways to look for the truth in a suspicious death investigation.

But he said collecting and preserving evidence is the key to understanding what happened at any death scene.

Sometimes investigators "assume too many things, therefore they don't investigate as closely as they should," he said.

"You only get one crack at a crime scene. ... If mistakes are made, there's nothing to be done about it," he said. "In any death investigation, regardless, you treat it like a homicide until you prove it's not."

Mathis added that women commit suicide far less often than men, and when they do, they are far less likely to use a gun than to overdose on pills. When they do use a gun, they aim for the heart, not the head.

"Women don't want to leave a mess for someone to clean up," Mathis said.

A year after Jennifer died, a new family is living in the small white house. Excellent tenants, the landlady said.

She said the family claimed Jennifer's possessions and papers, her Dodge Magnum and her van, within a few days after she died.

Bradley Clerk and Master Carl Shrewsbury said no estate had been opened in her name, which indicates she didn't leave a will.

Family members adopted the little girl.

They declined to be interviewed, saying they want to protect the child.

"Her daughter should not have to pay for her mother's choices, choices she made until she had no other way," said one of the girl's guardians, who believes Jennifer took her own life.

Though the child is healing and happy, the trauma lingers, the guardian said.

"My little girl don't even want me to wear red nail polish anymore because it reminds her of blood," she said. "She saw her mother's blood."

Contact staff writer Judy Walton at jwalton@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6416.