Brainerd levee system has worked for 33 years, yet federal rules require Chattanooga to raise parts

Sunday, May 18, 2014

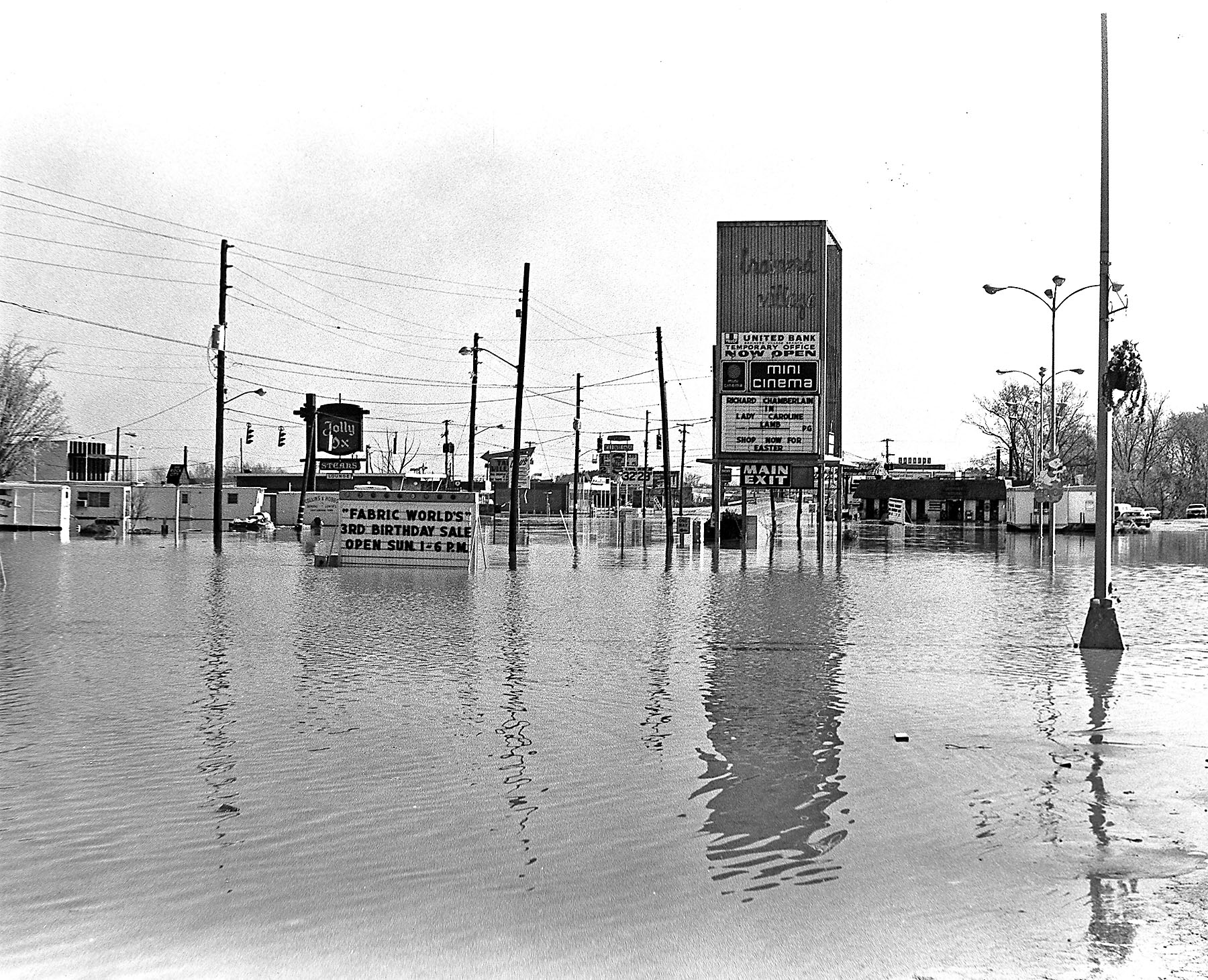

BRAINERD LEVEE HISTORY* 1973 - A major flood hit the Brainerd area, the last of a series that struck the area starting in the latter part of the 1960s. TVA agreed to design and build the levee for the city of Chattanooga.* 1980 - The levee was completed. TVA provided $14 million of the cost; the city supplied $1.1 million.* 1981 - TVA gives full ownership of the levee to the city but jointly inspects it annually as a courtesy until 2010.* 2010 - FEMA requests data from Chattanooga to show that the levee meets elevation requirements - including new data for Spring Creek * 2014 - Chattanooga puts levee construction project for bid. The deadline is 2016.• No representative from Chattanooga, FEMA or TVA could say when Spring Creek was modeled, or who studied it, by press time Friday.

For more than 30 years, the Brainerd levee system has done what it was intended to do - prevent the kind of flooding that submerged hundreds of homes and businesses around South Chickamauga Creek in the 1970s.

The system has done its job well, Tennessee Valley Authority officials say, and has likely averted more than $18 million in damage to the area since it was built in 1980.

But when the federal government says make it higher, you make it higher - or pay the price.

New flood calculations performed by the Federal Emergency Management Agency have raised the level to which protection must extend.

The result is that Chattanooga taxpayers have to spend an estimated $500,000 to increase the height of the dirt and concrete wall - or some 3,000 homeowners will see their flood insurance bills spike.

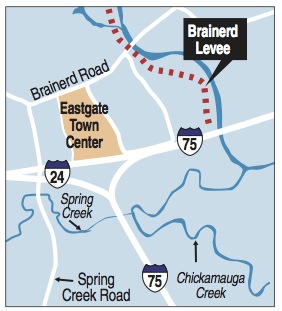

This new, higher high-water mark means that a 600-foot part of a secondary flood wall near Spring Creek no longer gives the 3-foot water clearance that federal rules require. And that span of secondary wall can keep the entire 3-mile-long Brainerd levee from getting FEMA's OK when the maps are finished.

Michael Barry, spokesman for the Insurance Information Institute - a nonprofit consumer information organization funded by the industry - says this story is playing out all over the U.S.

"I think what this instance highlights is the extent that FEMA is concerned with inland communities - not just coastal communities, but those situated around rivers and creeks," Barry said.

In most cases, new flood maps are showing flood zones in areas that were previously not included. And mortgage lenders are demanding that borrowers get flood insurance for their homes - even if they never had to before.

That means that residents who built or bought houses outside the official flood zone are being told they are at risk. The cost of flood insurance depends greatly on the flood risk in the community, Barry said. Flood insurance for an average home can vary widely - from a few hundred dollars a year to a few thousand dollars, he said.

Karen Ford, senior specialist for dam safety at TVA, says FEMA's latest push to update flood maps across the country has been a pain for many residents - and those in Brainerd are no exception.

But Barry blames the changes on the weather.

Weather events in recent history have prompted the harder look at inland communities, he said. Hurricane Irene in 2011 brought floodwaters in Albany, N.Y., and other eastern cities, where flooding had never occurred, he said. On the West Coast, Sacramento, Calif., is seeking to improve its levees, as well, he said.

In Brainerd the main levee structure is up to snuff. It was built by TVA after a series of floods the decade before and was later given to the city. The whole levee system is made up of a series of secondary flood walls, pump stations and berms built throughout the area.

Now the city is bidding a construction project to add height to the flood wall, make a contingency plan for flooding along Interstate 24 and raise a berm around a nearby pump station, according to Lee Norris, the city's public works director.

The flood wall hasn't been damaged, and it has never failed. But Norris said that when it was originally built, FEMA had flood data for South Chickamauga Creek, but not nearby Spring Creek.

"When they built it, Spring Creek had not been modeled. And TVA had just used historical data from South Chickamauga Creek [for FEMA certification]. At some point, Spring Creek was modeled, and that raised the flood elevation," Norris said. "When [FEMA flood mappers] arrived in Chattanooga, they gave us a heads up and said the levee isn't certified. If it's not certified, FEMA says it doesn't exist," Norris said. "So everyone behind the levee would have their insurance go sky high."

Once the adjustments are made to the system, the risk for homeowners in the Brainerd area should remain the same, said Mark Vieira, senior engineer with FEMA Region 4, which includes most of the Southeast.

Old maps show the area as protected, and the construction will ensure new maps will, too, he said.

Chattanooga has two years to show that all parts of the 33-year-old levee meet the criteria. Until then, the city has a provisionally approved levee, Vieira said.

"After the two-year period, we get the data that we need and we would take that note off and show the map as providing protection," he said.

But on the other side of the interstate, East Ridge resident Charles Snyder says it won't do him any good. He has always lived in the flood plain, and he has insurance bills to prove it.

He lives on the 1000 block of Spring Valley Drive, in the Edgewood neighborhood. His home is about 100 yards from Spring Creek, and that distance closes fast in heavy rains when the creek spills over its banks.

"Anytime Chickamauga [Creek] gets to 23 feet, you can start to see the water come up in Spring Creek," he said.

During a flood in 2009, one of his neighbor's cars wound up completely submerged. Several other neighbors had more than 10 inches of standing water in their homes. Parkridge East Hospital had to ferry patients into the facility in rowboats and on ATVs. One of Snyder's neighbors, who lives closer to the creek, keeps small boats in his basement to store his belongings in heavy rain.

"He just lets them float up," Snyder said. "I wish they would do something about it on this side, if they could."

Contact staff writer Louie Brogdon at lbrogdon@timesfreepress.com or at 423-757-6481.