Allied troops crouch behind the bulwarks of a landing craft as it nears Omaha Beach during a landing in Normandy, France. The D-Day invasion broke through Adolf Hitler's western defenses and led to the liberation of France from Nazi occupation just as the Soviet Army was making advances in the east, turning the tide of the war in the Allies' favor.

Allied troops crouch behind the bulwarks of a landing craft as it nears Omaha Beach during a landing in Normandy, France. The D-Day invasion broke through Adolf Hitler's western defenses and led to the liberation of France from Nazi occupation just as the Soviet Army was making advances in the east, turning the tide of the war in the Allies' favor.Once, their faces beamed with youthful promise.

Their legs carried them through the sand, then mud, then over the frozen ground of Europe.

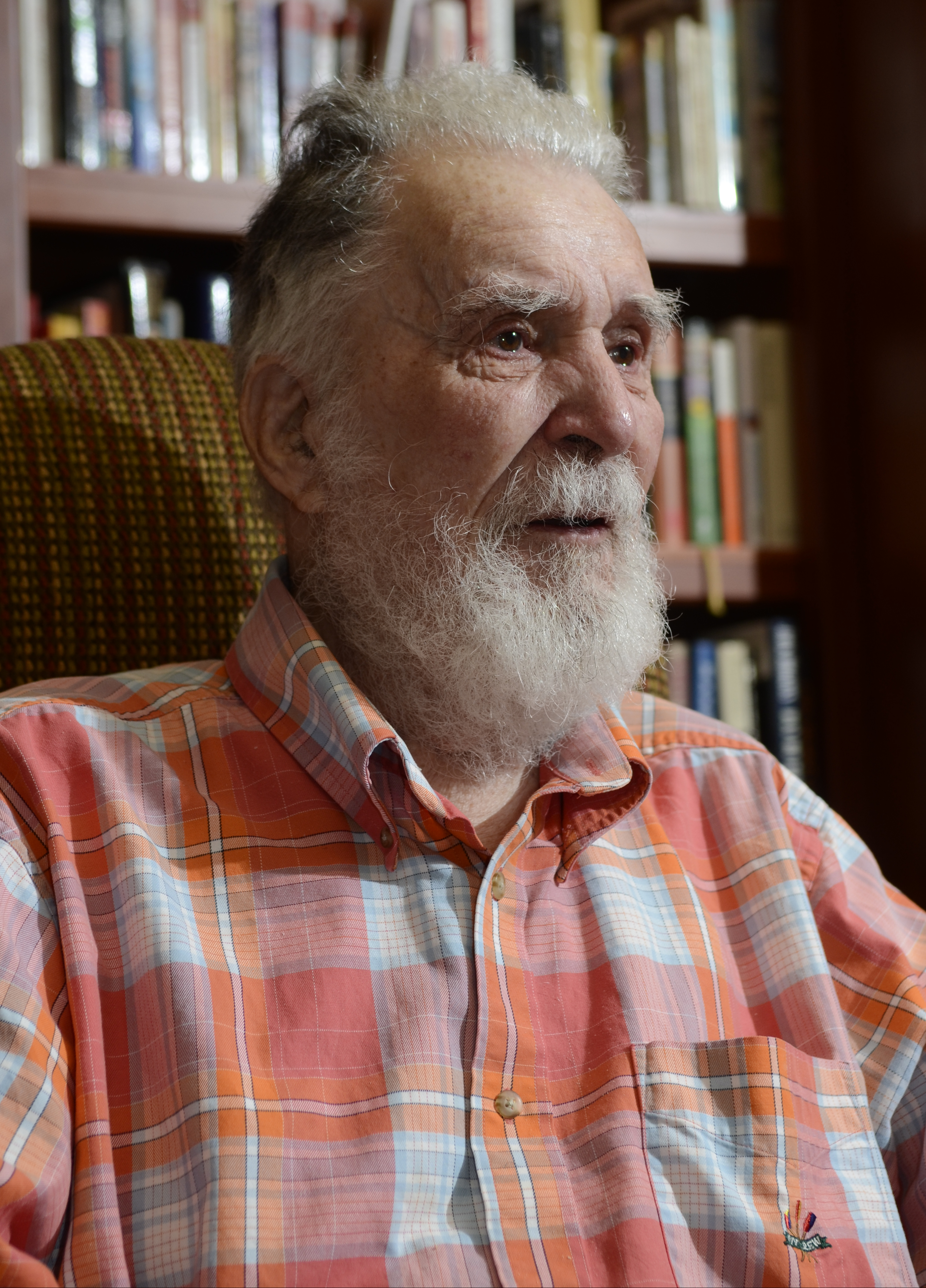

Now the decades have left their mark. Liver spots, shaky hands and faint hearing mark the men of the Greatest Generation.

Some dates escape them. Events in the valley of time between June 6, 1944, and today have faded.

But those days in uniform and the historic sweep of that invasion and its turn in the war forever mark them.

Today marks the 70th anniversary of D-Day, the Allied invasion of Normandy that gave Americans a foothold in Europe and ultimately led to the death of the Nazi regime in Germany. Much more bloody fighting would come, but that colossal June invasion put soldiers at Adolf Hitler's doorstep.

An estimated 7,000 ships of every type broke the horizon in the days of the landings. Those vessels hauled more than 100,000 soldiers onto the beaches after a sustained bombardment. Nearly 12,000 planes flew overhead, dropping bombs, supplies and paratroopers into the French hinterlands.

In the months of bombing leading up to the landing, nearly 12,000 Allied airmen were killed. The D-Day assault, which began June 6 but lasted until June 24, saw nearly 4,500 Allied deaths, according to the U.S. National D-Day Memorial Foundation. June 6 is often described as the "longest day."

Today,1.6 million World War II veterans are still alive out of more than 12 million who served during the conflict, according to census estimates.

Walker County native Fred Matthews, now 92, was working at a factory in Baltimore when the war began to rage in the years before the invasion. He signed up and was assigned to the U.S. Army's 29th Infantry Division.

He was a "replacement," a new soldier assigned to fill in when a soldier in another unit had been killed or wounded.

For a few weeks in advance of the invasion, the men of the 29th camped in England, waiting.

They had no conception of what was to come.

The space of a day separated Matthews from the worst of the landing. He loaded into a troopship and bobbed along in the Atlantic Ocean before stepping onto Omaha Beach on June 7.

German artillery rounds rained down from the hillsides as he gathered with his squad and they marched into the Normandy countryside.

His first taste of combat was in the dreaded hedgerows -- 15-foot-tall embankments where Germans lay in wait.

""We had to battle them out," said Matthews, seated in his wheelchair in the Life Care Center of East Ridge, where he now lives. "A lot of people got killed in the hedgerows."

Thomas Cash was in college in Kentucky, his home state, during the war's early years. There was a special program that required the schools to grant passing grades to students who were drafted during the semester.

So Cash sent a telegram to his local draft board and asked to be included in the next round.

"I signed it 'love, Tom Cash,'" he said.

A short while later he got a telegram back, " You're in, love, your local board," the 90-year-old Life Care of Hixson resident said, laughing.

Cash was trained as a criminal investigator for the U.S. Army's military police. He spent a few months in 1944 working with detectives at Scotland Yard in London, taking cases that involved American soldiers.

Some of the English were glad to have the Yankees; others were not.

"They had a saying about us: The American soldier is 'overpaid, oversexed and over here,'" Cash said.

In the weeks before the invasion his command pulled him and other military police back to provide guard and security for infantry units preparing to invade.

On June 5, 1944, Cash escorted Army Rangers to the Bristol Bay docks to load up and begin the voyage to Normandy.

The next afternoon he watched as airplanes flew endlessly overhead, towing three gliders at a time, all full of soldiers aiming to land beyond the beaches and attack inland.

Days after the invasion he was on the shores and headed to Cherbourg, a key early objective for the Allies. As he marched through the area he saw the aftermath of war.

Images at the village of St. Lo stay with him today.

"American bombers had absolutely flattened that city," Cash said. "I've often wondered what happened to those poor people."

Cash volunteered to fill in as an infantry fighter in the coming weeks. He lost close friends and good soldiers frequently.

Matthews was sent home a few weeks after the war in Europe ended in 1945. Cash was assigned to policing duties in Austria for a time and returned home on a ship that nearly capsized while crossing the Atlantic in a heavy storm.

Despite the sights and sounds of war and the pals lost, Cash said his most painful experience came after he was home. During a visit with the mother of one of his close buddies, she asked him to tell her how her son had died, omitting no detail.

He just couldn't. Seven decades later the memory brings tears.

Those losses, so personal, so close, haunt both men still.

"It's horrible," Matthews said. "When you see your buddies get killed right in front of you ... it's rough."

Contact staff writer Todd South at tsouth@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6347. Follow him on Twitter @tsouthCTFP.