FAST FACTS• More than 2,500 households live in the Chattanooga Housing Authority's 16 public housing sites.• Nearly 3,000 households get housing through private rentals paid in part by government vouchers.

Here lies public housing.

All that's left is to fill in the date of its passing.

Across the country and in Chattanooga, traditional large-scale public housing sites are being shuttered, the nation no longer able or willing to spend the billions of dollars a year it takes to maintain this crumbling part of the nation's social safety net.

On top of that, for all the good such sites have done in providing numerous people with temporary shelter while they get back on their feet, large concentrations of public housing have become associated with generational poverty and crime.

Instead, the strategy for housing the nation's poor is changing to small, scattered sites of dozens rather than hundreds of units, and the widespread use of vouchers to help clients pay for private rentals.

Under the weight of those issues, Harriet Tubman with its 440 units in 2012 became the latest Chattanooga public housing site to be vacated and closed.

It won't be the last.

With the Tubman sale completed just this month, officials with the Chattanooga Housing Authority already know that College Hill Courts and East Lake Courts - the city's oldest and largest public housing sites - will be the next to go.

Housing authority Executive Director Betsy McCright said she doesn't want residents to get alarmed, and neither site will be sold or demolished this year.

"There are no immediate plans for the demolition or disposition of College Hill Courts," McCright said. "However, the CHA recognizes that funding constraints are such that ongoing maintenance of the site to HUD's [standards] over the long term is problematic."

CHA will partner with the city, public housing residents and other stakeholders to develop a strategy for the sites that is in the best interests of the city and low- to moderate-income families, she said.

Officials say they don't want to vacate both sites at the same time, so College Hill Courts probably will go first. It will definitely be sold, vacated or demolished within the next 10 years and probably within five, said Naveed Minhas, CHA's vice president of development.

The picture is so clear for large-scale public housing that Minhas says residents need to prepare. His advice:

Strive to get a job and get out of public housing regardless of what's happening at the housing authority.

The housing authority is not going to leave residents "high and dry," Minhas emphasized. The agency will get vouchers for the residents before the sites close, he said.

Such talk frightens Lisa Rooks.

She worries about homelessness if the sites were to close. Hers is among more than 900 households at College Hill and East Lake courts.

"If they said you have a year to find a place to stay, that would be hard on me," said the 44-year-old disabled mother and grandmother who has lived at College Hill Courts for a total of 10 years. "I have nowhere else to go."

"Sometime in the very near future public housing as we know it will no longer exist."- Eddie Holmes, Chattanooga Housing Authority board chairman, speaking in 2011

Not all public housing in Chattanooga is doomed. Senior sites are here to stay for at least two more decades, Minhas said.

CHA's four sites for seniors, Boynton, Dogwood, Mary Walker Towers and Gateway, house about 670 seniors.

Some other sites, mostly those that are in better condition, may be around for awhile yet, too.

The housing authority is doing a $16 million renovation at Emma Wheeler Homes, and all 340 units of public housing standing when the renovation began four years ago will still be available for residents when it's complete in 2015. The units will have new roofs, upgraded interiors, new kitchen appliances, new floors and upgraded electrical wiring.

There are several reasons CHA decided to invest in that site, Minhas said.

With Maurice Poss Homes demolished, Harriet Tubman sold and East Lake and College Hill getting more expensive to maintain, CHA wanted to make sure it had at least one large family site still available. Emma Wheeler was smaller than East Lake and College Hill, and Emma Wheeler had $6 million in energy savings gained from a partnership between CHA and Honeywell. That money is included in the site's renovation.

Other sites being considered for renovation are Boynton, CHA's largest senior site with 250 units, and Cromwell, a CHA scattered site with 206 units. Renovations at Cromwell will include new roofs for the units. Minhas said it would take seven to 10 years to get Boynton and Cromwell up to standards, and when the authority is done with those developments it won't have any money left for College Hill.

But public housing as it has been known here since 1941 is indeed going away, piece by piece.

Eddie Holmes, chairman of the CHA board, acknowledged as much in 2011.

"It's not tomorrow," Holmes said, "but sometime in the very near future public housing as we know it will no longer exist."

Holmes on Tuesday said he stands by his statement.

"The money is going away," he said. "If you don't have the same level of funding, how can you maintain the same level of service? They're reducing our funding every year."

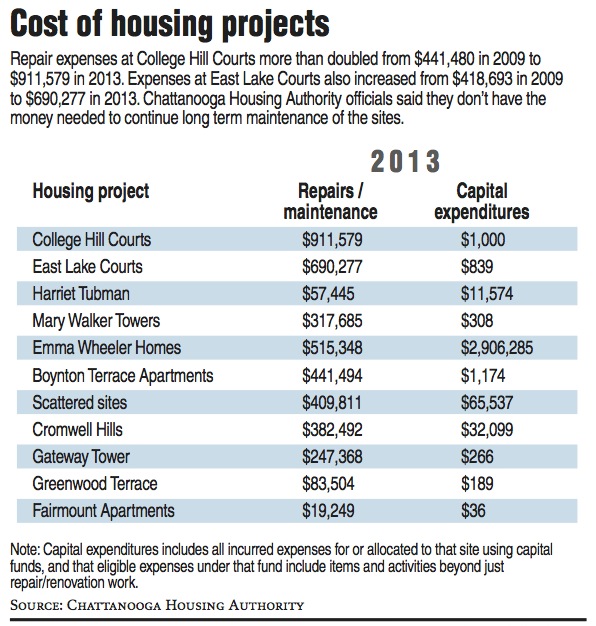

CHA officials said it would take $100 million to bring both College Hill and East Lake courts - both built in the 1940s - up to HUD standards. This year CHA received about $3.7 million for repairs at all of its 16 housing sites. And further funding decreases are expected, Minhas said.

"The cost for maintaining them is getting to be more than what we have," said Holmes.

The federal government gave $1.8 billion to housing authorities across the country this year to cover brick and mortar repairs to the nation's 1.1 million units of public housing. But the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development estimates that the units need an estimated $25.6 billion in large-scale repairs.

Without the money invested in repairs, the country has been losing about 10,000 public housing units a year, mostly due to disrepair, according to HUD officials. In all, an estimated 260,000 units have been demolished or otherwise removed from public housing since the mid-1990s, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a Washington, D.C., nonprofit research and policy institute working on federal and state fiscal policies and public programs that affect low- and moderate-income Americans. Only about one-sixth of those have been replaced with new units.

In Chattanooga, more than 600 units of public housing have been destroyed or sold in the past 10 years, with the demolition of the 188-unit Maurice Poss Homes in 2005 and the pending demolition of the Harriet Tubman housing development.

Meanwhile, more money is going toward private housing vouchers here. Through payments to landlords, CHA is putting more than $20 million a year back into the community, Holmes said. That pays to house nearly 3,000 households. That's more than live in public housing today, just over 2,500 households.

But there haven't been enough landlords willing to accept government-issued vouchers to house all the people who have them. About 85 to 100 people now have vouchers but have been unable to find a rental. The number of vouchers available also depends on funding from the federal government. More than 1,000 people in Chattanooga are waiting to receive vouchers, though 250 are scheduled to be issued in early May.

Even so, CHA is moving ahead with plans for East Lake Courts and College Hill Courts.

CHA will start community-wide discussions about both sites at the end of this year when the agency develops its five-year plan, Holmes said. But Minhas said discussions may come sooner since the housing agency has put the Harriet Tubman sale behind it. The city closed on the purchase of Tubman from the housing authority this month.

Rooks worked for more than 10 years in child care and nursing before rheumatoid arthritis and a nerve condition left her unable to work and without income. So even if the housing authority gave her a voucher for housing, she couldn't pay the utilities, she said.

Except for needing a new roof on some buildings, College Hill doesn't need a lot of repairs, she said.

A little water runs down her walls when it rains, and the paint chips when she wipes them. A small strip of mold lines the ceiling above her washing machine, but none of that is cause to move, she said.

For Rooks and others like her, Holmes offers a piece of advice as well: Vote for elected officials who will fund public housing.

"Public housing gets funding depending on who is in office," he said.

Have politicians in Nashville and Washington who are sympathetic to your cause, he said.

In the past, residents thought their needs would be taken care of by Washington or the state, but that isn't true, he said.

"Public housing is changing. The funding stream is changing. The money isn't available," Holmes said.

"Residents should get involved with who they elect for office," he said. "That's going to determine the outcome of what happens to our sites."

Contact staff writer Yolanda Putman at yputman@timesfreepress.com or 757-6431.