TAKE A LOOKInterested in seeing how Google's new comprehensive map has changed the Scenic City's virtual landscape? Download Google Earth for your PC or Mac at earth.google.com or download the smart phone app for Apple or Android mobile devices. The new models should be enabled by default. But if not, look in the box on the left-hand side of the screen and make sure there's a check mark next to "Photorealistic" in the "3D Buildings" section.

Chattanooga long has touted itself as the Scenic City, but until a few weeks ago, those who visited via the Google Earth digital globe might have questioned the legitimacy of that claim.

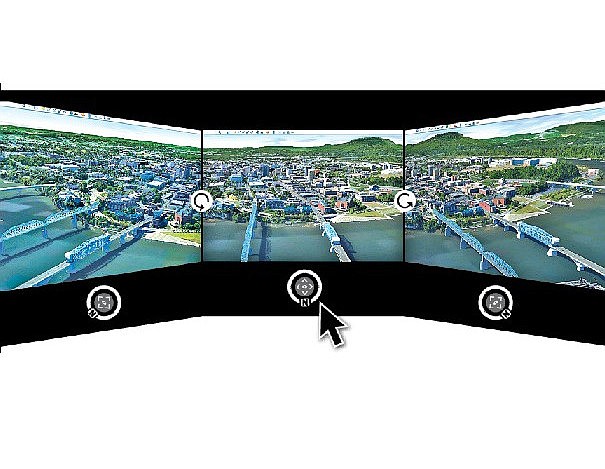

The detailed satellite imagery used in Google's free mapping software looked fine when viewed from above. But from other angles, the city appeared to be featureless flatland with two-dimensional buildings pasted onto it.

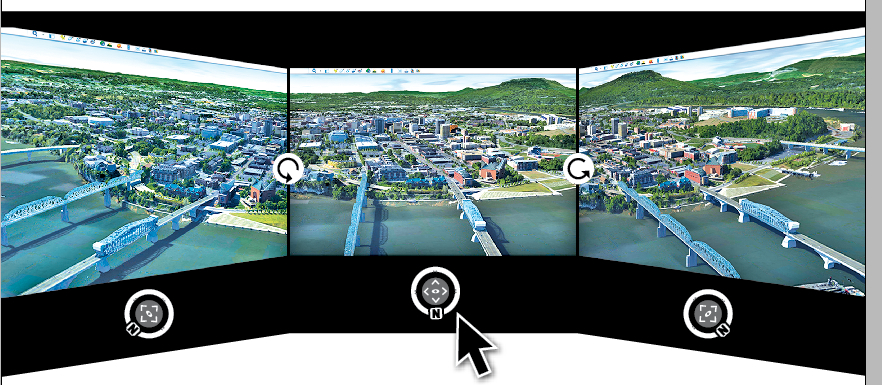

Earlier this summer, however, Google gave Chattanooga a boost into the third dimension courtesy of a new mapping process that automatically generates detailed virtual models of every building, bridge and tree in the city.

When the updated imagery went live earlier this summer, Chattanooga was the first major city in Tennessee to receive a 3D upgrade. In an emailed response, Google couldn't indicate any reason why the Scenic City was at the head of the line.

"Publishing 3D imagery hinges on a variety of factors -- everything from data complexity to computing and resource availability," wrote Susan Cadrecha, Google's communications senior associate of maps, in an emailed response.

"There was no reason specifically for Chattanooga to go ahead of other [Tennessee] cities, but we are looking forward to expanding 3D coverage in the future."

The models created using Google's new approach don't always bear up under close scrutiny. Some buildings appear distorted, causing them to appear to have been constructed from melting taffy. Because of how Google's algorithm interprets them, streets with a thick canopy of trees -- as is in the Fortwood Historic District downtown -- can sometimes mistakenly be modeled as green tunnels.

What the technique lacks in finesse, however, it makes up for in comprehensiveness. Every building in the city, from AT&T Field to Hamilton Place Mall, has been virtually replicated.

Prior to Google's new technique, generating virtual models for Google Earth was a laborious process. Users first had to take photographs of each side of a building and apply these images as a texture "skin" to a model created using 3D modeling software. The final model then had to be submitted to Google to be reviewed before being placed on the virtual globe. From start to finish, the process could take several months.

In a June 2012 post to Google's official blog announcing the new mapping technique, Google Map vice president of engineering Brian McClendon explained how the company had streamlined its modeling process by using a fleet of camera-equipped planes.

By making multiple passovers of a city from four cardinal directions and combining those building profiles with top-down satellite imagery using an algorithm, Google is able to generate models much more quickly than any manual process, McClendon explained in a 2012 interview with CNET.

"The ability to generate this imagery automatically means that, just by using computer vision, we can generate large swaths [of models], much larger than has been available," McClendon said. "With this methodology, we can cover the entire cityscape ... with just algorithm."

Google's first batch of 3D-mapped cities went live in June 2012, enabling users to virtually explore close-to-exact digital replicas of major cities such as San Francisco, Boston, Los Angeles, San Antonio and Rome.

Over the last two years, Google has extended 3D coverage to many mid-size cities, including Louisville, Ky., Greensboro, N.C., and Montgomery, Ala. Chattanooga's 3D upgrade went live in June and extends beyond downtown to outlying areas, such as Signal Mountain and Harrison to the north and North Georgia towns such as Ringgold and Flintstone.

Weeks after Chattanooga's map data was updated, Nashville and Memphis also received the 3D treatment. Knoxville, however, remains mostly flat, save for a handful of models created and uploaded to Google by users.

In the days when Google's user base was generating models on its own, that degree of coverage wouldn't have been possible, said Chattanoogan Wes Mohney, who built a career out of creating 3D models for Google Earth and other applications.

"That's way more modeling than I, as one person, could ever handle in years, so it's a step in the right direction," he said.

In May 2011, Mohney founded Market3D, a geo-modeling and visualization firm, which contracted out modeling services to local companies as an urban planning and marketing tool. He says modeling contracts with Market3D eventually provided half his income.

Mohney was also a major contributor to Chattanooga3D, a local nonprofit organization of designers, architects, engineers and students who sought to create virtual likenesses of Chattanooga's downtown in Google Earth.

Chattanooga 3D was formed in 2009 during the Chattanooga Stand 48Hour Launch community visioning process as an "experiment with a new kind of civic engagement." Eventually, the concept of a virtually explorable downtown led to a partnership between the modelers and River City Company, which sought to use the digital cityscape as a tool in marketing and business recruitment campaigns.

For several years, the members of Chattanooga 3D and other volunteers hand-crafted models of more than 150 buildings, mostly in downtown and peripheral locations such as Glass Street and Southside. Their efforts even attracted attention from Google, which featured Chattanooga 3D on its official blog for SketchUp, the primary software used by Google Earth geo-modelers.

In 2012, however, Mohney caught wind that Apple had acquired C3 Technologies, a company that used missile technology to generate 3D maps automatically in a process similar to Google's new approach.

Seeing the writing on the wall, Mohney said he decided to phase out his dependence on Market3D before his services became obsolete. He now works for American Exchange, an individual health insurance brokerage operating out of the Business Development Center on Cherokee Boulevard.

Even though the automatically generated models don't yet provide the kind of photographic resolution of a user-generated model, the technology is on-pace to achieve the same level of detail in short order, he said.

"I think it's still useful and headed in the right direction; we're just not there yet," Mohney said. "It'll have even more uses eventually because an exponential number of things will be modeled than even a group of modelers could accomplish."

Despite Google's new automation of the mapping process, Chattanooga 3D's founders, husband-and-wife duo Karen and Stephen Culp, said their group's work wasn't wasted effort and may even have lead to Google mapping Chattanooga ahead of Tennessee's other cities.

"Chattanooga 3D served its purpose well," Stephen Culp said. "As we learned about Google's own tech transitions, we devoted more time to the bigger picture, which ultimately led to bigger citizen-led initiatives like [local crowd-sourcing website] Causeway."

"[Chattanooga 3D] learned how to use Google's unique tools and then were able to noticed. That's how we got where we are now," Karen Culp added. "I think we helped each other."